Part 1 (of 6)

Mirrors, selves, interiors, theatre, photography

Sarah Pucill in conversation with Nina Danino (2020/2024)

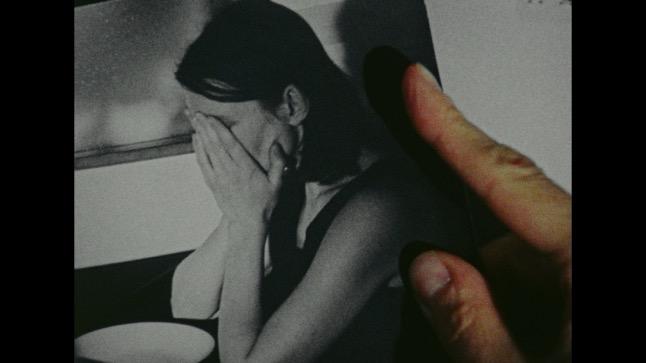

Sarah Pucill standing in front of a photographic print from the film Stages of Mourning (2004).

Photo:Nina Danino (2020). Courtesy of Nina Danino and Sarah Pucill.

_______________

Shaped from an online conversation and subsequent emails between the artists during and after the first COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in the UK, this text captures an extended and ongoing conversation between artists Nina Danino and Sarah Pucill. They later revisited their discussion in 2024 and Sarah Pucill read the manuscript for the Introduction text.

________________

In 2007, Sarah Pucill curated the programme The Subjective Camera (2007), which included work by Nina Danino along with other artists who have taken part in this series of conversations.[1]

They both also took part in a roundtable discussion on ‘Women’s Experimental Film at the LFMC’ in 2015.[2]

They met in the late 1980s, when they both attended some of the same screenings at the LFMC and other spaces in London. In this conversation, Sarah Pucill discusses the context around artist’s moving image and experimental practices of the 1990s and now. She outlines how her work

engages with the relationship between women, the possibility of language, the centrality of the female subject as a feminist act and the use of artistic references in her work. Towards this aim, she talks about the importance of staging in her films, the role of photography, the use of mise-en-scene and camera framing, discussing the roles she and others play as performers in these works. The material creation of decorative tableaux vivants in her work includes performers, objects, props and fabrics, which use the visual language of the film set, the craft of set design and which strongly reference theatre. There is also the parallel craft and skill involved with using16mm to achieve these visual stagings, mostly set in interiors. The filmmaker’s self-reflection and notion of selves is presented through these stagings.

The discussion also considers how Sarah Pucill’s work is informed by three decades of study and engagement with film, feminist and visual theory. This critical knowledge and questioning inform the conversation, conducted in her home in July 2019. They work through the lesbian gaze and particularly, the use of mirror in her films, which is symbolic – a reflecting object, a metaphor for the idea of multiple selves. The metaphors of reflection and self reflection are also a strong thread in her process of production and making films. They are integral to her visual syntax, which uses materials and props to establish her unique language of self reflection as an experimental filmmaker.

________________

This conversation is one of a series of six discussions undertaken by the filmmaker Nina Danino in 2020. They were revisited and edited in 2024/2025 when they were published online.

Please note that the opinions and information published here are those of the speakers/authors and not of LUX or the wider research team and institutions involved with their funding, transcription and publication.

Published online by LUX, London (2025)

Editing and research: Claire M. Holdsworth (2020/2025)

________________

Conversation

Recorded 25 July 2019 and 4 March 2020 (London)

_____

Nina Danino:

Thank you for this interview. Should we open with how you started making your early films?

Sarah Pucill:

My first film You Be Mother (1990) in a sense came out of my own practice directly rather than specifically from experimental film. I had previously been working between sculpture and painting. I was painting with sand and I was working across distorted images of my face, then it moved from 2D to 3D, into a photograph and then after that photograph I wanted to make a film from the photograph. Milk and Glass (1993) was made out of – or from – You be Mother (1990). I was interested in something between the interior and the exterior, so the self-portrait is a façade.

I think my first film You Be Mother, looking back now, determined much of the exploration that I continued with in nearly four decades and even now. In fact, it's a challenging of the ideal of self-portraiture – the idea of anything that can be a self-portrait. It’s not replacing one thing with another, rather it's much more a concept of thinking about the split and multiple self – is it image, is it object, is it voice, is it the veneer, is it the inside or the outside? It’s a whole set of relations of self and the world where others and the inanimate are part of that and this is very much there in my first film.

Nina Danino:

Your image appears in black and white photographs of close ups of your face and eyes in You Be Mother. There is the use of projection and of framing and reframing, images of yourself and in Stages of Mourning (2004) you are seen with a set of photographs, as they are scattered on the floor and you lie down on them. They are also pinned on walls and you pose in front of them. How did you engage with the concept of the feminist need of saying “I”? Was it that concept that made you decide to start using your own image and staging yourself for the camera, to use yourself in front of the camera, not rather than, but as well as, taking the role of a director behind the camera?

Sarah Pucill:

I was very influenced by the work of filmmakers and artists like Chantal Akerman, Maya Deren, Claude Cahun, Francesca Woodman, Cindy Sherman between photography and film, also even Barbara Hammer, Jayne Parker, Sandra Lahire. Feminist and many queer feminists who were particularly interested in this in the 1990s, to particularly explore what it is to be in front and behind the camera. Obviously as we know from the feminist theory that was raging and very active during the nineties, this concept of being both object within a frame and at the same time the author who frames, edits and lights that body, really challenges the way in which we understand the mainstream language of film, where the female is objectified and “over there”. Instead, the female has agency and is authoring herself – that is important. But, just as important is to dislocate the idea of the individual as separate, the idea of an identity that is stable, defined and not connected with and part of, others and the world.

Sarah Pucill, Stages of Mourning (2004). Copyright: Sarah Pucill.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Could you talk about your work in relation to the self-portrait? I see the construction of your films as a questioning of the self-portrait where the portrait of the performer to camera is always in question. A performer who poses, dons disguises, costumes, dresses up is a practice which seems to come from theatre. In her essay on your work ‘Between Mirrors’, Helena Reckitt also draws attention to the curtain in your films.[3] The curtain opens to the stage, are you a master of ceremonies as the director as well as a performer? There is also the aspect of disguise. The wig appears in your films worn by yourself and performers and in Swollen Stigma (1998), Cast (2000) and Phantom Rhapsody (2010), you use masks and self-masking. Also, there is a recurring figure of the doll which seems to have a central role in the theatre of your film world.

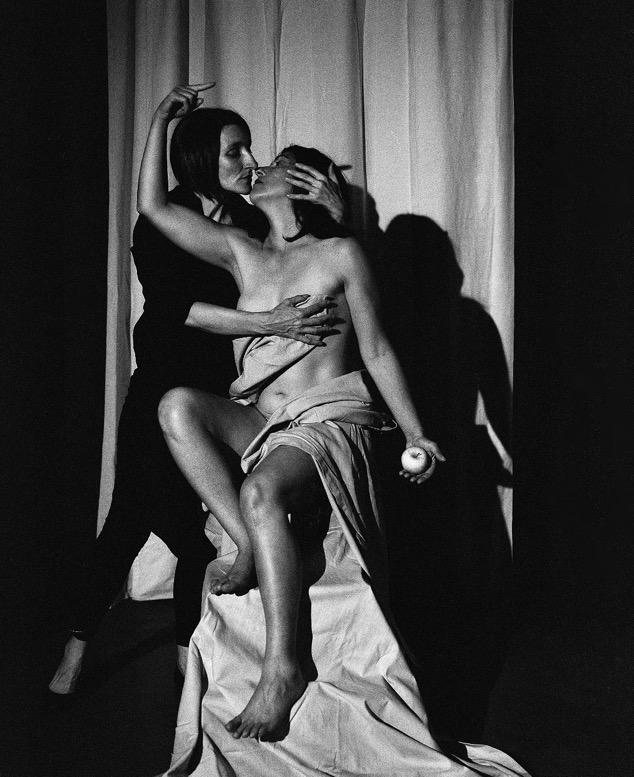

Sarah Pucill, Phantom Rhapsody (2010). Copyright: Sarah Pucill.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Sarah Pucill:

Yes, the process of thinking about the self is to be invented, to be reinvented, to be constantly in flux – that was very much there. My work on the French photographer and artist Claude Cahun, Magic Mirror (75 minutes, 2013) [and Confessions to the Mirror (68 minutes, 2016)], speaks to this and with this, but it’s there earlier also in the films before, which include Phantom Rhapsody (2010) and Fall in Frame (2009).

Nina Danino:

There are many props and objects in the films, one of the most predominant is the mirror. Does that relate to the idea of the presentation of multiple selves? The reflection is fragmented, at angles, the mirror can set up infinite space, a mise en abyme in some passages of films, reflecting the camera back to the audience. The reflected and filmed pictorial space is interchangeable. Is this mirror related to the surrealist mirror or to the later mirror of Lacan, whose work you have said was an influence on your films?

Sarah Pucill:

I’d like to, first of all, say that the use of the mirror for me comes out of two spaces. One is a reflexive modernist language that comes out of structuralist film for example some of Guy Sherwin’s films that incorporate use of mirrors or the work of Conceptual artists such as Dan Graham. It’s a meditation on what the camera is, because a camera is a mirror, inside the camera there is a mirror. Photography and film are reproductions of mirrors, it’s about the rectilinear frame.

At the same time, it comes from something else. It comes from a feminist place i.e. the dressing table mirror. When did I first encounter a mirror? My sister and I were given mirrors to put on a chest of drawers in our bedroom and my two brothers weren't. This for me is so important, there is a different relationship. Why did I have this, why didn’t they? Why was it so central, so unspoken of? I wanted to assert this question of difference. This intensity of self-image, particularly the face for women, is really core, and something I really wanted to interrupt. I remember, as a child my mother would sit in front of the mirror and be there for a long time before she would leave the house. I’m only thinking about this now. I remember being frustrated that I couldn’t get out of the house because my mother was still there in front of the mirror. There is an intensity that I want to speak of. That we don't speak of. There is no language and I wanted to interrupt that whilst masculine modernist reflexive practices were doing something else with mirrors, like Dan Graham’s Performer/Audience/Mirror (1975) a performance which I love, but I wanted to throw in gender.[4]

Nina Danino:

Taking My Skin(2006) depicts a relationship between yourself and your mother and the mirror. The camera also part mediates the relationship. You hand the mirror to each other. She's reflecting you and then you take over and then you reflect her. That is a metaphor which fits in with what you've just described in terms of an early memory and the relationship that the mirror has in your films. And you’ve used the mirror with yourself and other performers in other films.

Still form Sarah Pucill, Taking My Skin (2006).

Copyright: Sarah Pucill.Courtesy

of the artist and LUX, London.

Sarah Pucill:

I'm working with myself very often and I can't literally be in front of the camera and behind –technically I can't. I think that performers often become a surrogate for myself. This is so much so, that for example in Magic Mirror (2013) I was writing about what I’d been doing in the film and I forgot that it wasn't actually me performing but somebody else [laughing]. So, yes, it is a strong identification.

Nina Danino:

Another reflection is of the figure of a female Narcissus from the Greek myth of Narcissus who falls in love with his own reflection. It appears in Swollen Stigma(1998), which feels like a signature film of yours and at a time when there was experimentation with narrative in experimental film and women’s film in particular from filmmakers like Lis Rhodes, Jayne Parker. There is a scene in Swollen Stigma where the face of this female Narcissus is lying down by the pool spilling a milky liquid into the water and it’s deep night. The sound is not naturalistic. We hear sounds of scraping, thuds, scrunching which are amplified and are not connected to the image but they create a psychological connection.

Sarah Pucill:

Yes, it's interesting that you're picking up something that I think is a really important image and it's nice to hear that you're putting it together with that scene in Swollen Stigma that I had forgotten about. In Swollen Stigma the image of Narcissus brings together what I’m trying to do in terms of a different sexual gaze: that's what that film is really wanting to explore. The milk coming out and going into the water is to consider something umbilical – nothing is about certainties or fixities actually but an imaginary. I was trying to explore lesbian imaginary which is key, and it is there in Cahun’s images and it is there in her text. I put them together in both films Confessions to the Mirror and Magic Mirror.

Nina Danino:

Can you say more about a lesbian imaginary?

Sarah Pucill:

Yes, I made the film Cast in 2000, inspired by two images by Claude Cahun. One of herself looking in the mirror looking at the camera and one of her partner Marcel Moore looking at the camera. I made a whole film out of that in the film, a theme of moving through a mirror, of the lesbian kiss.

In Cast, I was referencing the film Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) by Maya Deren, and The Blood of a Poet (1932) by Jean Cocteau: taking the theme of moving through a mirror and the lesbian kiss. It has a feminist context. What we see in Meshes, when Deren moves through a mirror […] for her, it’s a death. In The Blood of a Poet, the same movement through a mirror reflection is a gay man’s intimate encounter. In my film, it's a female queer encounter. It was very important. At the end of Cast, there are feet on soft sand, after the first lesbian kiss. This sequence shows images from Cahun’s writing in Disavowals (1930): ‘More easily than I would have thought possible and without leaving a trace, I pass my fist through the window. Drunk with new extraordinarily harmonious sensations, I was crossing a beach, my feet on soft sand’. A moment later Cahun continues 'At these shores I linger, unsure of the language of flowers'.[5] This passage has significance for other films: I have kissing flowers in Swollen Stigma. The lesbian imaginary comes from what that experience is. It’s different to a man sleeping with a man. It's different to a woman sleeping with a man. In Mrs Dalloway Virginia Woolf described the match in the crocus, which I illustrate in Swollen Stigma,[6] but bare feet on soft sand came from something of a lesbian experience, women have softer skin. In other words, it is not a coincidence that Cahun’s description of ‘soft sand after lesbian encounter of moving through the mirror’ reflects my imaging in Cast.[7] (I was unaware of Cahun’s text at that time).

Nina Danino:

Phantom Rhapsody seems to reference early cinema and the studio of early cinema pioneer Georges Méliès. It connects with the 1930s and the transition from theatre to early cinema as a popular form of entertainment. It connects also to Expressionism in early German cinema and filmmaker Lotte Reiniger’s magical animation; to the importance given to dreams and other animated techniques in the Surrealist artistic movement – all of which are occurring during the same period and context of Claude Cahun, as she was coming-up in the twenties and thirties.

Francesca Woodman and Claude Cahun portray themselves in their photographs as isolated figures who appear and disappear both implying modes of magic conveying something psycho-dramatic going on in an interior world. In your films there is a certain sense of the filmmaker as a lone figure and the use of surrogate performers. There is no dialogue and performers generally don’t act naturalistically, but seem detached.

Still showing Sally Pucill in Sarah Pucill, Swollen Stigma (1998).

Copyright: Sarah Pucill. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Swollen Stigma combines surrealist imagery with symbolism. There is a woman who is the protagonist who sits in an armchair in a semi-lit living room interior. There is a body hanging upside down, objects appear and disappear, close ups of the protagonist pulling at her eyelashes. The domestic interior – it could be set in the filmmaker’s home/studio.

This is itself intense.

The home as setting for experimental films has a history in women’s filmmaking probably starting with Maya Deren who filmed Meshes of the Afternoon (1948) in her Hollywood home. But also it implies a non-division of labour between home and work nor hours divided into leisure and work but everything is work and un-demarcated. Working from home in terms of filmmaking suggests an autonomous world where you have control of the production. This can be the attraction of experimental films to women. In the filmmaker’s home as studio, we lose a sense of time and connection with the outside world. It can also imply isolation. One of the freedoms of experimental film is that it can cut itself off from the world and re-organise space and time as does Meshes of the Afternoon famously.

Experimental film simply, because of the way in which it can control time and cut itself off from the world can both be anachronistic or asynchronous with the fetish of the ‘contemporary’. Is this a liberation for women filmmakers?

Sarah Pucill:

I think it is liberatory, thinking about film as a medium, and as a capsule in time. I remember seeing the films at the LondonFilm-makers’ Co-operative [LFMC] as being from another place, from another time, that were both important to me. The crossing of time and place is a great thing. I wrote recently about how the approach taken by artist Isaac Julien in Looking for Langston (1989) was an influence on the work that Sandra Lahire did with Sylvia Plath.[8] It has been an influence for me on the work I’ve done with Claude Cahun. I remember Issac Julien saying that as a Black gay man in London in the eighties, there was no enabling reference for him, nor was there anything around the London Film Co-op [LFMC], which was really relevant. He took another time period, 1920s New York, and connected to the Black gay scene surrounding the gay African American poet Langston Hughes. It was closer to him and that’s what he needed to do – to travel in time and place.[9]

I think that the emphasis on the need for the contemporary obviously comes out of capitalist culture. I was interested to loosen myself from that through thinking about co-authorship, not even thinking about the new but about a piece of work as an interpretation of an earlier artist’s work, letting go of that sense of authorship to some degree. The emphasis on the new and the new author is quite hysterical really because if you don’t look to history, what is ‘new’ doesn’t mean anything.

Nina Danino:

You shoot all your films on analogue what is your affinity with the photographic craft of film and the aesthetics derived from 16mm film?

Sarah Pucill:

I’ve always to-date made films on 16mm. It has informed how I think, especially having edited on 16mm with sound and image initially. I think understanding the technique can be an important part of a film. The filmmaking has always been for me not just of what I'm filming or how I want it to be seen at the end, but the process of putting the film in a camera, setting up the frame, putting the shots together, thinking about sound, this is the film. The language of framing, what I juxtapose with what, is the film. The fact that you don't see it when you film, you have to wait until it comes back. The fact that it’s expensive, you have to wait for funding and you have to value what you've shot and find a way to work with it. This process is very different and it has been very difficult for me to adjust to the digital. It's about valuing the slowness of it and the time that you give it, it impacts on what you do and the process. It is getting to the point that now everything is in conjunction with digital, since making Stages of Mourning in 2004 I have shot on film and edited on computer. I think what I have been wanting to do is enjoy the materiality. Even since before I was making film, I was making sculpture, I was painting, I was making objects. That continued through to where I think my filmmaking involves as much what I do with the set as what I do with a camera, where I'm exploring the relationship between what happens in front of the camera and what happens behind.

Nina Danino:

You also make all the props and objects for the films. Is the handmade important and what does it mean to you to make the props yourself.

Sarah Pucill:

Well, I sometimes make the props, I also recycle or find props. In the last two Cahun films this element has comes to the fore. I think the handmade or hand sought is important, because I also recycle and find props too, they are improvised, they are not so finely done. They don’t get tidied with craft, there is this constant interrelationship which actually becomes chaotic. There are moments of very fine details which are attended to and moments where there is actually chaos in the improvisational element of making them in my own home. It’s actually a small space. The limitation of what's possible is always rubbing up against what I can do because I'm doing everything. I'm interested in that relationship of being in different roles and having some assistance, but also taking authorial control, so having control and losing control – something about the in-between of that, is what I’m interested in.

Nina Danino:

But it is more than producing. The subject/ive is not just about making – making is only a start. But it is intrinsic to your engagement with the process that you make these things yourself and therefore this is also your personal investment. Would you delegate it?

Sarah Pucill:

It's the improvisational which is the inventiveness. If I hand it to somebody else – in the same way that if I hand the camera to a professional or the edit – I’m going to get something back that is standardised. It's going to be the same as an advert because the whole of production is standardised. If I hand it to somebody and say make me all of those, then they come back all produced. I'm interested in what isn’t standardised. It’s not about a craft but it’s about improvising through something that’s inventive and playful.

Nina Danino:

In this film, Confessions to the Mirror (2016), are you more in the role of director?

Sarah Pucill:

No, I still did everything myself.

Nina Danino:

The film set of Confessions combines real objects with projections of other objects. Everything seems to have been given specific role and place in the tableaux. There is equal attention to small objects as to the seemingly more important larger props, such as an ornate frame. One is a glass urn and inside it are some tiny decapitated dolls’ heads which become animated. Small objects come alive. A small artist’s mannequin holds a flowerpot sprouting tiny plumes. There is attention to the smallest objects and details.

Sarah Pucill:

Those images that you're talking about are re-stagings of Cahun’s photographs – her works using still life and objet trouvés (found objects).[10] She photographed highly detailed small sculptures with an unstable status; were they photographs were they sculptures? A few were presented as sculptures, but they also had the status of a photograph. I’m quite interested in that. What is the object[11], what's the performance, what's the photograph of a performance, what is it to restage?

I have used macro and close-up a lot in my films. It is something that comes out of Surrealism, Surrealist photography and Surrealist film, which did influence my work. I enjoy that splitting between a carefully produced still life and a photograph which is similar to Cahun’s portraits which split between ‘is it her or someone else?’. It breaks expectations. I did make these objects, then I animated them.

Confessions to the Mirror was a huge challenge, because I worked with Cahun’s writing Confidences au miroir (1945-1954) a memoire of her time in the resistance in Jersey during the Second World War. Different voices speak in English and sometimes in French, lines from Cahun’s text over re-staged images from her photographs. It was a huge task to undertake, the translation, the editing of text and then the re-staging of it. The memoire serves in part, as a testimony of Cahun and her partner Marcel Moore’s political propaganda campaign in Jersey under the Occupation.

The voice in the film narrates moments from their imprisonment and the impact on her health and in a sense early death because of it. I felt a responsibility and I had to prioritise the fact that Cahun’s writing (in Confessions) is a testimony to what both Cahun and Moore sacrificed and risked on Jersey island during the Nazi occupation. It weighed on me heavily how to do this. What am I doing, what right do I have to be working with her words and these images. How to do this as a long film so that people would stay and at the same time I could be inventive in how I restage the images and bring together something of the text and the image and do something that is not just copying. I’d say that the theme of collage is actually very central to both of my films about Cahun, how I collaged her writing with the images. It was a lot of work.

Still from Sarah Pucill, Magic Mirror (2013).

Copyright: Sarah Pucill. Courtesy

of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

You are the maker and a set designer, the producer, camera woman behind and you perform in front of the camera and also direct performers. You also do the jobs that in a standard production would be delegated to a runner or assistant who might find the props, from a feather to a velvet curtain.

Sarah Pucill:

That's the chaos yes. That's the chaos. Where do I get this from, where do I get that from? I was very driven to make Confessions to the Mirror and it was in impossible circumstances in terms of where I was working in, which is my home. I didn't really have the funds to be doing this. It was at my cost financially, but I was desperate to do it.

Nina Danino:

This gives the film’s intensity.

Can we go onto some context? What was your relationship to the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC] in terms of this need to make films? When did you start going there?

Sarah Pucill:

I think what I experienced there was seeing a lot of films, both early Surrealist films (by artists like Germaine Dulac, Alice Guy or Deren, whom we mentioned), films from 1960s (Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith and Andy Warhol) and 1970s structural and post structural, as well as feminist and queer work, especially when Laura Hudson and Helen de Witt and were curating. I started going in 1988, 1989 when I was a student. I saw films there, a lot of radical work from different influences or fields of practice that impacted on me, that weren’t directly from my context in London. Because of the time capsule element of film (which we mentioned before), I was exposed to work happening elsewhere, at another time.

Other artists that I met there including Sandra Lahire, Sarah Turner (who was at the Slade) and Alia Syed, Vicky Smith – yes that was part of the context. Other key filmmakers possibly are Lis Rhodes, Jane Parker, Su Friedrich, Barbara Hammer from the US, or Ulrike Ottinger, she’s somehow there.

Nina Danino:

Did you engage with the feminist debates and aspects of psychoanalytic theory?

Sarah Pucill:

Yes, massively. I was going to everything throughout the nineties and buying and reading every book and pretty much everything on feminist theory [laughter]. And from that I was reading about the question of difference, and essentialism in terms of feminism, trying to negotiate that. This had an important impact on me. Luce Irigaray also wrote about relationship between women.[12] Irigaray together with Julia Kristeva and Hélène Cixous (the French feminist theory trio), were exploring ways to give definition to that which is other to phallocentricism, including the relations between women.[13] I know there is homophobia and both Kristeva and Irigaray, and that psychoanalysis generally finds this work hard to accept, but as an artist I find the poesis in the writing useful in terms of creating imaginary alternatives to phallocentric language and thinking. I made a choice that my artistic references would be female, whatever the cost might be.

Nina Danino:

And were you influenced by theories of the gaze of the time?

Sarah Pucill:

Yes, I was interested in the gaze, thinking about the option for film to reinvent outside of the conventions that were, and continue to be, patriarchal.It’s not just the form of representation but how, to re-think language, not just how we see the female in a frame – it’s not so literal – but actually the whole language. Much lesbian and feminist filmmaking retains hetero-patriarchal structures of viewing. Experimental film has that potential to unseat that fixity.

Nina Danino:

Did you have your work distributed by the London Film Co-op [LFMC]? There was an assumed choice to be made between being at the LFMC or going to Circles. Even though Circles [later Cinenova] was a distribution organisation dedicated to showing works by women, the feminist films from Circles/Cinenova’s were focused on putting across feminist social issues.[14] Did you also distribute your work through the LFMC?

Sarah Pucill:

Not at the LFMC, I did submit my first film You Be Mother – and that was given a lot of exposure. The artist Moira Sweeney was working at the Co-op [LFMC] and programmed it. It went all sorts of places and possibly there was one screening at the Co-op [LFMC]. I didn't get so much shown there, but Cinenova [formerly Circles] was active and they did support me a lot. It was Cinenova which gave committed representation.

My work was in the LFMC catalogue, so it was occasionally shown. I think Sarah Turner did one screening programme that toured called 'Hygiene and Hysteria' and included my film 'Milk and Glass', whereas Cinenova were much more active and sent it to festivals such as Feminale in Cologne [Germany] or Pandemonium Moving Image Art Festival 1996, London Film Festival and there was always a screening in London.[15] Although I was supported by the Arts Council [of Great Britain], which had a dedicated Film Unit in terms of funding, actually there was no publicity or very little. They were one-off screenings, it was pre internet. The galleries didn’t show it, and the cinemas didn’t, it was just in rare small spaces such as the LFMC, which then became the Lux Centre, and later the distributor ‘LUX, London’.[16] After it closed there were not many screening spaces (in the early 2000s). There was the small cinema at the ICA [Institute of Contemporary Arts, London], or another small cinema at the Whitechapel Art Gallery and odd other pop-up venues, which had been there for a while anyway.

Nina Danino:

The LFMC was at the end of its fully operational period in 1988/89. Even though the LFMC was still based at the same Camden premises it had been in since 1976, it wasn't operating fully between 1992 and when it moved to the Lux Centre in 1997.

Sarah Pucill:

I had support from the Lux, where I had two retrospective screenings, and one at the Tate Britain in 1998.[17]

Nina Danino:

That’s when, in the late 1980s and early 1990s some film artists started to be shown in the gallery.

Sarah Pucill:

You say that, but I only remember a very few artists moving to the gallery in the late 1980s. It was very few, mostly from the US plus artists like Douglas Gordon, and some women artists associated with the YBA [Young British Artist] movement, Gill Wearing, Sam Taylor-Wood but it was a tiny amount, a handful literally I would say. Video did have this history, there were monitors in the gallery through the 1980s. In the nineties it was still this handful, mostly men.

Nina Danino:

Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho in 1993, at the Hayward Gallery [London].[18] was Alfred Hitchock’s Psycho (1960) slowed down. Thus it became an appropriated object or ‘found footage’. The emphasis went from the maker to the viewer, the reception, the critic, and curator, to the artist. Here there was a shift when the work of a Hollywood director can become conceptual art work and the YBA’s picked up on this idea of the conceptual artist with regards to art appropriation. Does it make it meaningless, or does it add a new meaning? In some cases the artists become curator/producer as well. The installation/screening was a relaxing experience and thus with a non-differentiated type of viewing where you lose yourself in the large scale projection. What was your experience of showing single screen experimental film in the nineties in this context, and of the Lux Centre closing in 2001.

Sarah Pucill:

Even though there was less support in the nineties, things were still active, things were happening. There were still spaces at the Whitechapel Gallery once a year dedicated to artists – because there were fewer of us, things would happen. The moment that transition took place, when all artists were making moving image – that's where the invisibility of experimental filmmakers occurred. At the same time, all the state supported structures for distribution disappeared.

Nina Danino:

What about the writing on experimental film? Much of the writing on artists’ film in Britain focussed on the structural period of the 1970s or artists’ moving image from the 1990s onwards. Recent anthologies blend the wide range of diverse practices in moving image.[19]

In the eighties Undercut, the magazine of the LFMC, was one of few publications dedicated to experimental film in the UK. After Undercut, there was Vertigo which focussed on independent film (edited by Marco Zee-Joti). Contemporary art journals and magazines such as Frieze, Art Forum did not write on experimental film until perhaps later only on historical figures such as Jonas Mekas. Moving Image Review and Art Journal, MIRAJ established in the 2000s published on individual artists making film or moving image but by then an experimental film sector didn’t exist as a movement as such.[20]

Sarah Pucill:

It’s a fact that there is more literature on women experimental filmmakers from the US than in UK.[21] For example, the book Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks, edited by Robin Blaetz.[22] Even though it was published in London, all the work is by US artists. Another series by Scott MacDonald included a lot of women.[23] The UK publications that focussed specifically on experimental film have given only marginal space to the women filmmakers. Some gallery based artist anthologies have included a lot of women, but this is not always a specifically experimental film context.

Nina Danino:

Experimental film – except for historical figures as stated – isn’t really shown in the art world of galleries, art fairs and biennales, there is beginning to be interest by researchers though. There is interest in this progressive period in the 1970s and 1980s. Maud Jacquin subsequently curated the programme Reel to Real at the Tate.[24] Emile Shemilt, Mary White who has researched slide/tape, Kathryn Siegal working with artists’ publications in the 70s.

Sarah Pucill:

I’ll answer if I can, about critics not writing about the area of experimental feminist film. I went to many conferences on this subject. During the 1990s there were many. Some were organised by Griselda Pollock on feminist art history, others on feminist film and some on psychoanalysis and queer studies. Laura Mulvey was often speaking, along with other theorists like Jacqueline Rose and Judith Butler ‘On feminist film criticism’. At that time the ICA [Institute of Contemporary Arts, London] was a very central place for time-based media in terms of screenings and critical debate.

I remember at one particular conference, committed feminist writers and critics, all day long were passionately talking about how so much feminist critical writing was focussing on mainstream films, the classics by Alfred Hitchcock and big Hollywood filmmakers and why there was comparatively so much less writing on women’s experimental film practice? Laura Mulvey advocated that what needed to be done was to make films that critique patriarchal structures of filmmaking, and that start to offer something else. Although I can’t remember which conference this was, at the end of a long day I distinctly remember a couple of women writers saying that the reasons for not writing about experimental or alternative feminist films had to do with career issues, that it could be suicide to dedicate hard earned time-off from teaching to write on an artist or group of artists that are unknown, because of course that makes it harder to get the writing published.

Of course, it becomes a spiral, less visibility of the work and less visibility of being written about. I feel that artists need to write about their work. It is important to be doing this and in a sense all filmmakers who have taken up space are often filmmakers who have had their writing published.. This includes the pioneers who set up the LFMC and wrote about work, Peter Gidal, Malcolm Le Grice. They also supported themselves through teaching in art departments rather than film studies. They inserted what they had done through their own writing. I think this needs to be done.

Nina Danino:

Yes I hope that is what we’re contributing to now.

Sarah Pucill:

I think I wanted to work with film before I got to the Slade. I actually studied theatre, painting, music and dance for my BA before the Slade. I was performing, working in Super 8 [8mm format film], I started making films then. I saw early Surrealist films and animations actually. It was at a cinema, outside the course I was doing in Manchester, but nonetheless it was impressionist for me. It was a BA in Combined Arts, at Manchester Metropolitan University (the Slade was a postgraduate course), my selected areas were Fine Art and Theatre studies, so integration between different artforms was core to the course, visual theatre and Performance Art were important elements.

I saw a lot of Eastern European Surrealist animation, including by Czech animator Jan Švankmajer, the Quay Brothers and the very early surrealist film by Luis Buñuel, L'Âge d'Or (1930). On the course, Samuel Beckett plays were being put on by students all the time. Before I arrived in London and discovered the contemporary art scene, I was making films. Probably now, looking back, that all had some impact.

Nina Danino:

That's interesting, it all makes sense now in terms of your interest in staging.

Sarah Pucill:

I was studying with Douglas Gordon, and also Sarah Turner, Alia Syed, Mairead MacClean, and there was a whole different scene in Manchester. Although, my tutors were all from the London Film-makers’ Co-op and impacted on me – people like Stuart Brisley, Susan Hiller, Jayne Parker, Lis Rhodes, and the artist Chris Welsby, which was a scene that I wanted to embrace. The politics of feminism I felt, could best be done through filmmaking because film is active literally and politically. I understood from the feminist film landscape at the time that pervaded books, films and conversations, all that I was being exposed to, that this space for experimental film was a very important space for critiquing and offering alternatives.[25] What is important is that it was not about critiquing but about making. That seemed such an important valuable thing to do. I was married to the idea of making alternative, critical and economically independent films and didn't think about the gallery thing which I thought was just commercial.

Nina Danino:

And how is your work shown today? Where do you show it, is it in festivals and in galleries?

Sarah Pucill:

I'm currently making a film installation for Ottawa Art Gallery in a group show on Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.[26] I'm taking a section from Confessions to the Mirror (2016) using water reflections, so the installation is a re-working of a part of the film into something new. I made two long films because I believe in it as a form that is serious and committed. I value the long-form as an artist’s experimental work because you're not shoved against other shorts in screening programmes. You actually take up a substantial space and there’s usually a question and answer session. I even think that you can have long film in a gallery but there are people who will say, no you can’t. You can, people will stay; when I showed ‘Magic Mirror’ at the Nunnery Gallery, people did stay. When they are committed, they’ll go back but I am experimenting now with installation.

Nina Danino:

What are your thoughts about making experimental film as a form now? Obviously, the context for experimental filmmaking, which included seeing women's work, showing and discussing it was the context in which it flourished. Also making work in relation to and alongside, often in the same space as other filmmakers, disappeared as an infrastructure. Do you see it as a historical moment?

Sarah Pucill:

I'd like to pick up the last bit, on experimental film within the context of contemporary fine art, which is the subject that I have taught for three decades. Within this environment, which tends to focus on commercial galleries, art museums, the art press, experimental film largely isn’t acknowledged within this sphere. I was part of two recent touring screenings of women’s experimental film, one curated by Maud Jacquin for the Tate Modern (the Reel to Reel programmes we mentioned before) and another by the curator Selina Robertson and artist Beverly Zalcock. Only one of these was funded, with those working on the other unpaid. The Tate screening went to a few venues internationally. This is all I have witnessed recently. Even today, Cinenova are unfunded and operate not as distributors but as curators with an archive, which means there is no accountability to the filmmakers in the archive. Experimental film artists are not therefore supported in the way for example an artist is – who is represented by a gallery or by a distributor. My point is that with regard to> publicity which affects the funding of experimental film, you can’t get funding from The Arts Council if there is no gallery to show the work and this work doesn’t get shown in galleries and it is unlikely to be reviewed after one night’s screening. It is the nature of a single screen film that unless there is funding, it can’t survive with visibility within the commercial sphere that we have in the UK now, and this was different in the eighties.

Experimental film is not really about the now - that's true, but that doesn't make it not an interesting thing to seek out in a book or to actually see that work now, which makes it contemporary at the time of viewing. We’re talking about this ‘now’, as a moment in the past. The past is only ever lived in the present. That time period ‘in the past’ of woman's work is relevant for me ‘now’ and in this sense is actually contemporary.[27] I'm always thinking about my work in terms of other female artists historical and contemporary, who have been my influence. It’s my reference point. Many of those artists working in the eighties and nineties are still making work now.

Nina Danino:

In the late eighties, early nineties there were screenings of women’s experimental film at the London Filmmakers’ Co-op which followed those programmed by Laura Hudson, Helen de Witt, Sarah Turner, Moira Sweeney, Sara Maitland-Carter, Emina Kurtagic and Felicity Sparrow and Lis Rhodes at Circles and the film theorist Bev Zalcock’s programmes for City Lit London. Then experimental film became the subject of anthologies such as A.L. Rees’ A History of Experimental Film and Video (1999), David Curtis’ A History of Artists’ Film and Video in Britain (2006).

So, we are talking about an approach to experimental film. Film has a material emphasis, which is a different relationship to what is termed artists’ moving image. The critical context in the seventies and eighties in the UK developed film practices which combined theoretical rigour with material practice. There is a relationship between a material practice with a subjective emphasis in these conversations. It is being considered as a particular, perhaps unique set of relationships. Having these conversations is a way of trying to work out this particular place of practice and its material, historical, contextual, critical intersections and how we are practicing now. <

Sarah Pucill:

It is very true what you are highlighting here Nina, the crux is the relationship between the film material that was and can only be through the hands-on relationship we had with the celluloid, and cameras and how that connected with both an emotional but also theoretical political critique. These women were reinventing their language of deconstructing patriarchal film structures and finding new spaces of language. What really matters first of all is that it's an incredibly valuable history and moment in time and it hasn't been acknowledged. It's very important to have this work remembered and seen and understood and I'm sure that it will be. There's so much there.

These films that we are speaking of are important and in many cases (examples in this interview series) almost entirely unacknowledged, were funded by the Arts Council of Great Britain [later Arts Council England], by the BFI [British Film Institute], by Carlton Television (who funded my work), in other terrestrial television channels, including Channel Four’s department dedicated to independent film and video and workshop funding (during the eighties). I am thinking of artists like Jayne Parker and you who received funding from Channel 4 and initiatives like the London Production Fund. The British Council funded people to take their work to festivals, to distribute it. There was a lot of financial support for this work in the eighties and nineties. Institutions like the LFMC, then LUX, Circles/Cinenova, Four Corners, and other institutions nationally were funding to support this work.

The work was important enough to invest considerable sums for production and distribution. These filmmakers studied and are or were teaching at the Slade, Goldsmiths University, the Royal College of Art, Kingston School of Art, Central Saint Martins, the University of Westminster. They were making important work that was acknowledged in Europe and was circulating internationally. The demise of funding for this has meant that to a significant extent the door was closed, and this needs to be revived for posterity.

I find from discussions with students that there is a huge interest, in people wanting to know about experimental film and in particular feminist and women’s practices within it. I think it will take time for it to be threaded through, for people to see that this isn't the same as doing a performance and recording it. The difference is that the visual language is what conveys its meaning and its artistic merit – which might also engage with less obvious forms of communication such as what the images represent or what a voice is saying. Rather, the point in experimental cinema, is the signification of the language. In this way, otherwise invisible or unconscious elements are given space and considered. It is less about what we see in literal terms, for example a man crossing a road; but instead it is the camera position, lens frame, lighting, static or hand held, the exposure, the edit decision, sounds that might counter what you see in front of the lens, the speed. Simply put, it experiments with language but towards different ends. Often artists’ moving image is about what is ‘recorded’ and the content. This more literal approach dominates much current work where an overriding idea or concept is imposed upon the film. The visual language itself is on the whole treated as if it were a transparent form, i.e. the communication of the film form is invisible.

Nina Danino:

The films discussed in these conversations are in the place of a subjective position. In the programme you curated, The Subjective Camera you say that the individual filmmaker is at the centre of their own filmmaking process.[28] The technical and theoretical rigour combines with the filmmaker’s subjective investment, that was all part of the visual language of the work.

Sarah Pucill:

For the Subjective Camera screenings that I curated, the subjectivity of the film and the filmmaker is also inhabited by the spectator. This is how I understand it and why I am still happy with the idea of the subjective (and this inhabitation is significant in my Cahun films).

I think that element of subjective inhabitation is absolutely central, it is very important particularly the lived experience of an artist negotiating social and political contexts through an embodied aesthetic, where image and sound and movement are coming together in a highly controlled work. We are not speaking about wanting to celebrate individualism; instead, it is about seeking a freedom that might open up new spaces, of resisting the subtleties of conventions that make up the languages we live in. I think of Sandra Lahire, yourself, Jayne Parker, Lis Rhodes, Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki and others included in this collection of conversations. These practices are highly crafted and composed.

That sense of composing something, what’s important about inhabitation is that it is not just the literal. It is not just about employing the use of the first person, ‘I’, this is more like the process where there is a close relationship with the materials so unconscious elements become embedded in the work. For example, as I was saying to you about suddenly thinking about my mother in front of the mirror when I was a small child. That had never occurred to me before. It’s hitting me now as we speak about it – this may be because my mother has just died. The point is that when something is unconscious in the work, this is where things start to speak in ways that are beyond the literal or the known.

Nina Danino:

Yes, that is a really important insight from this conversation although it is there as well in the unconscious of the film. It is also part of the need to make the film which is inscribed in the film’s unconscious.

Sarah Pucill:

You live it. It is part of the unconscious: you are not aware of it but it’s there all the time. Simply put it is about not being obvious and allowing readings of the work to take time. I remember seeing a film of Jayne Parkers and then 10 years later I thought “now I understand what that is”.

Nina Danino:

To finish, earlier on you were talking about the subconscious as a way through which you could understand how you might be a subject in your work. This seems to be something that partly one has control over, but partly it's something that is a drive or need, that has an influence on one’s work, without you necessarily recognising it at the time, although later on one can reflect on it. Because after all, experimental films are a form about what can’t be verbalised and that’s precisely why we have practiced this as a form because it enables one to say what otherwise can't be said.

Still from Sarah Pucill, Confessions to the Mirror (2016).

Copyright: Sarah Pucill. Courtesy

of the artist and LUX, London.

Sarah Pucill:

Ultimately, what I see that the filmmakers from our generation have done, is to be working closely with the language of film as a material. That is the relationship between image, frame, edit and sound. I believe it is not nostalgic to acknowledge that the journey taken in making films in celluloid was a material engagement, I held it in my hand and this made for a particular kind of relationship with it, and this generation of filmmakers brought a feminist engagement through their subjectivity to the foundational context of structural and materialist filmmaking that at that time was taking up a lot of space in and out of the LFMC context.

Nina Danino:

Thank you for going into your films and their sources in such detail and into your working methods and as a visual language for self reflection.

Sarah Pucill:

Thank you Nina for conducting this set of interviews.

_____________________________________________________

Biographies

Sarah Pucill has been making 16mm films since 1989, with continuous support from organisations such as Arts Council England, the AHRC and +TV funding among others. These works have won awards at international festivals and been shown in cinemas and gallery museums internationally, including the London Film Festival, Welcome Institute, Institute of Contemporary Arts London, Tate Modern and Britain, the National Portrait Gallery, Royal Academy, White Cube Bermondsey, the Jeu de Paume in Paris and Anthology Film Archives in New York. Alongside her filmmaking she makes photographs from analogue negative, which have been published in Mirror Mirror: the Reflective Surface in Contemporary Art (Thames and Hudson, 2024) and Photography – A Queer History (Ilex Press, 2024). Alongside her practice, she has curated women’s experimental film programmes, such as for Frankfurt Experimental Film Festival in 2023, and written on her own film practice and related contextual artists’ work in publications including Cinematic Intermediality (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) and Experimental and Expanded Animation (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). Based in London, she has an MA from the Slade School of Art, a doctorate from the University of Westminster and is currently a Reader at the University of Westminster.

Nina Danino was born in Gibraltar. She is a Reader in Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. She studied Painting at St. Martin’s School of Art and Environmental Media at the Royal College of Art, London. She was a member of the London Film Makers’ Co-operative in the 1980s, a member of the editorial collective of Undercut: The Journal of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative (1981-1990) and co-editor of The Undercut Reader (Columbia University Press, 2003). Her films have been shown worldwide and premiered at film festivals and broadcast on television and a retrospective of her work took place at Close Up Cinema, London in 2016. MARIA (2023) is her fifth feature-length film. Her soundtracks feature vocals, singing, readings, narration and music in her own voice and in collaboration with singers and musicians. Her recent work crosses into stand-alone audio, live performance and studio recording.

_____________________________________________________

Select Bibliography

Blaetz, Robin (ed.). 2007. Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks. Duke University Press.

Butler, Alison. 2002. Women’s Cinema: The Contested Screen. Wallflower Press.

Cahun, Claude. 2024. CANCELLED CONFESSIONS or Disavowals (Aveux non Avenus). Translated by Susan De Muth. Thin Man Press.

Cahun, Claude. 2007. Disavowals.

Cixous, Hélène, and Clément, Catherine. 1996. The Newly Born Woman. Translated by Betsy Wing. I.B. Tauris.

Curtis, David. 2007. A History of Artists’ Film and Video in Britain. British Film Institute.

Howgate, Sarah. 2017. Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun. Princeton University Press / National Portrait Gallery.

Irigaray, Luce. 1985. This Sex Which Is Not One. Translated by Catherine Porter and Carolyn Burke. Cornell University.

Irigaray, Luce. 1985. Speculum of the Other Woman. Translated by Gillian C. Gill. Cornell University Press.

Kaplan, E. Ann. 1988. Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera. Psychology Press.

Kristeva, Julia. 1984. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. Colombia University Press.

Mellencamp, Patricia. 1990. Indiscretions: Avant-Garde Film, Video and Feminism. Indiana University Press.

Mulvey, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16 no.3 (1 October): 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6.

O’Pray, Michael (ed.). 1996. The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926-1995: An Anthology of Writings. Arts Council of England / John Libbey Media / University of Luton.

Pucill, Sarah, 2020. A Dialogue with Claude Cahun: Between Writing, Photography and Film in Magic Mirror and Confessions to the Mirror. In Cinematic Intermedialities, edited by Marion Schmid and Kim Knowles. University of Edinburgh Press.

Pucill, Sarah. 2019. ‘Coming to Life’ and Intermediality in the Tableaux in Magic Mirror (Pucill, 2013) and Confessions to the Mirror (Pucill, 2016). In Experimental and Expanded Animation: New Perspectives and Practices, edited by Vicky Smith and Nicky Hamlyn, 231–256. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pucill, Sarah. 2014. MAGIC MIRROR: A film by Sarah Pucill. LUX, DVD.

Pucill, Sarah. 2006. The ‘autoethnographic’ in

Chantal Ackerman’s News From Home and an Analysis of Almost Out and Stages of Mourning. In Experimental Film and Video: An Anthology, edited by Jackie Hatfield, 83-92. John Libbey.

Rabinovitz, Lauren (ed.). 1991. Points of Resistance: Women, Power, and Politics in the New York Avant Garde Cinema 1943–71. University of Illinois.

Reckitt, Helena. 2014. ‘Between Mirrors’. In Magic Mirror [screening catalogue], 1–17. Tate Modern/Tate Gallery.

Rees, A. L. 1999. A History of Experimental Film and Video: From the Canonical Avant-Garde to Contemporary British Practice. BFI Publishing.

Webber, Mark. 2007. The Subjective Camera. The Secret Cinema: Avant-Garde Cinema & Artists’ Film and Video, 25 April 2007, accessed 9 February 2025. https://www.markwebber.org.uk/2007/04/subjective-camera.html.

Sarah Pucill Filmography (2025)

You Be Mother (16mm, black-and-white / colour, 7 minutes, 1990). Funded: Julian Sullivan Award, Hull Time Based Arts. [Oberhausen Best Experimental Film Award, Atlanta Film Festival Experimental Film Award].

Milk and Glass (16mm, colour, 10 minutes, 1993). Funded: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Backcomb(16mm, colour, 7 minutes, 1995). Funded: Carlton Television; London Production Fund.

Mirrored Measure (16mm, black-and-white, 10 minutes, 1996). Funded: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Swollen Stigma(16mm, black-and-white / colour, 20 minutes, 1998) Funded: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Cast(16mm, black-and-white, 20 minutes, 2000). Funded: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Stages of Mourning (16mm, black-and-white / colour, 20 minutes, 2004). Funded: Arts Council of Great Britain; Arts and Humanities Research Council, AHRC.

Taking My Skin (16mm, black-and-white, 35 minutes, 2006). Funded: Marion McMahon Women’s Experimental Film Award; Arts Council of Great Britain; Arts and Humanities Research Council, AHRC.

Blind Light (16mm, colour, 20 minutes, 2007). Funded: Arts Council of Great Britain, Arts and Humanities Research Council, AHRC.

Fall In Frame (16mm, colour, 20 minutes, 2009). Funded: Arts Council of England.

Phantom Rhapsody (16mm, black-and-white, 20 minutes, 2010). Funded: Arts Council of England.

Magic Mirror (16mm, black-and-white, 75 minutes, 2013). Funded: Arts Council of England.

Confessions to the Mirror (16mm, colour, 68 minutes, 2016). Funded: Arts Council of England.

Eye Cut16mm, colour, 20 minutes, 2020)

Double Exposure(16mm / Digital, 27min, 2023)