Part 6 (of 6)

Inscriptions, jouissance: saints, mystics, visionaries, icons. Formats, soundtracks, voice

Nina Danino, a dialogue with Helen de Witt (2024/25)

Nina

Danino in front of a projection of her film MARIA (2023), Ince’s Hall Theatre,

Gibraltar (2024).

Photo:

Mark Galliano. Courtesy of Nina Danino.

_______________

Shaped over the course of a back-and-forth email conversation between artist Nina Danino and curator Helen de Witt over several months in 2024, this discussion was initiated in 2024 when Nina Danino returned to a series of conversations she had undertaken with artists in 2020, in preparation for their publication by LUX as an online collection. This dialogue is the final instalment in the series, which was originally initiated by Nina Danino just before the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020. As the interviewer in the other conversations, her filmmaking was not the main focus of these earlier discussions with women practitioners whose work she has reflected on over the years. This sixth conversation in the series, this exchange aimed to find space to reflect on Nina Danino’s own practice as a filmmaker. Her examination of how artists are inscribed in/through material filmic practices, as discussed in the other discussions in the collection, is significant to her long-term formulation of ideas around the subjective in writing and filmmaking.[1]

Helen de Witt has shown and written about Nina Danino’s work since the premiere of her film Temenos at the Lux Centre in Hoxton (London) in 1998 – a programme that included her other films “Now I am yours”, (1992) and Stabat Mater, (1990).[2] As a programmer, Helen de Witt’s mode of engagement with a diverse array of film practices and her sustained writing on Nina Danino’s work bring a depth of knowledge and a sense of affinity framed by these long-term interactions. Helen de Witt has written at length about Nina Danino’s work, including for the sleeve notes of the film soundtrack CD of Temenos (1998).[3] Her essay ‘Transfiguration and Transmediation’ is also included in the monograph Visionary Landscapes: The Films of Nina Danino (Black Dog Publishing, 2005) and the essay ‘The Persistence of Spirit: The Films of Nina Danino’ was published on Luxonline in 2004.[4] These writings explore themes of sacred place and cinema, a woman-centred filmic experience of ‘jouissance’ (discussed in the conversation below) and her approach to the religious as mediated through materiality, using ‘the cinematic apparatus as a means of revelation’.[5] Helen de Witt’s extraordinary ‘Sacred Places’[6] programme – shown at the Lux Centre in 2005 – included Temenos and in her long-term role as a Curator at the British Film Institute (BFI) working on the Experimenta artists’ moving image strand of the London Film Festival, she also later showed I Die of Sadness Crying for You (2019), part of a deep-dive screening and discussion at the 63rd LFF in 2019, just when Nina Danino initiated this series of conversations.

For their written exchange, Helen de Witt revisited Nina Danino’s films, connecting these works to the collaborations and networks surrounding her practice – an important aspect of all the interviews in this collection, which consider Experimental film and the subject/ive at the London Film-makers’ Co-op. From Nina Danino’s time as a student at the Royal College of Art in the 1980s to networks around the LFMC, cultures of experimental film, including funding bodies and organisations in the 1990s and 2000s and the demise of the London Film-makers’ Co-op (LFMC), their discussions span a number of important transitions over their respective careers.

________________

This conversation is one of a series of six discussions undertaken by the filmmaker Nina Danino in 2020. They were revisited and edited in 2024/2025 when they were published online.

Please note that the opinions and information published here are those of the speakers/authors and not of LUX or the wider research team and institutions involved with their funding, transcription and publication.

Published online by LUX, London (2025)

Editing and research: Claire M. Holdsworth (2020/2025)

________________

Dialogue

Written between August and December 2024 (Gibraltar / London)

Helen de Witt:

Your work has been made over four decades now, and your practices have evolved in complex and fascinating ways. It might be useful to start at the beginning, to talk about how you emerged as an artist and filmmaker, especially as I’ve been revisiting your films over the last few weeks. I’ve been thinking about the autobiographical elements across your filmmaking. You were born in Gibraltar – which makes you British although not born in Britain.[7] How has this unique cultural setting had a continuing presence in your filmmaking, could you talk about it further? In what way specifically has it affected your practice?

Nina Danino:

I came to study in London in the 1970s. I have lived in London ever since – so my formation as an artist has really been in London. Nevertheless, many of the sources in my films and materials draw on connections to Gibraltar and southern Spain. The singing of a saeta, in Stabat Mater (1990) comes directly from the south.[8] Gibraltar is an expanding territory in other works such as Meteorologies (2013), I Die of Sadness Crying For You (2018) and The Straits Trilogy on which I am working now, which will be filmed in Andalusia. Important and deep sources such as the voice, music and cinema come from there and are evident in many of my films.

Helen de Witt:

You mention moving to London at a time when cinema and experimental film cultures were really thriving, here and all over Europe. As well as these formative themes, what major influences or works by other artists did you discover in London that inspired you? Where there other influences of any form, from any other places or periods of time?

Nina Danino:

Before London, cinema had an impact – one film in particular, The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) by Pier Paolo Pasolini, which was screened for my school in Gibraltar in around 1968, two years or so after it won a prize awarded by the International Catholic Film Office (around 1965-67). The neo realism in the film stayed with me. I had an out-of-mind, out-of-body awareness of my own experience of the suspension of disbelief. I felt at that moment I was initiated into a cinema of a different order.

I happened to see La Strada (1954) by Federico Fellini on the state-run Spanish television channel TVE. I have strong early cinema memories of Spanish children’s films, which I saw at the Theatre Royal in Gibraltar (now demolished). At the 1950s Queen’s Cinema in Gibraltar, I saw the Mexican version of La Caperucita Roja [Little Red Riding Hood] (1960), directed by Roberto Rodríguez, which struck me with terror.[9] Later, my film Communion (2010) was projected as a film installation in the same Queen’s Cinema building in Gibraltar – so I returned to these impressions in some ways. At the installation screening, a black-and-white image of a young girl in white was projected on the 25-foot cinema screen in the vast 860-seat empty cinema for three days in silent vigil.[10]

I revisited the music culture from my memory later, through YouTube, when I started to research I Die of Sadness Crying For You (2019). There was the Spanish and Latin American sound but to this was added the new British invasion and rock music. There was the local Gibraltar Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) Radio and British forces radio, where we got all the new music in the 1960s and 1970s. There was also progressive music, live jazz and rock bands. Bare Wires (1968) by John Mayall was my first album, and the track Don't Worry Kyoko (Mummy's Only Looking For Her Hand In The Snow) on the album Fly (1971) by Yoko Ono and The Plastic Ono Band was my first avant-garde rock song.

The Straits [of Gibraltar] in the late 1960s were also on the hippie trail to Tangier in Morocco, so all the psychedelic music flowed through the air waves and on albums, but it was beyond the horizon. Because Spain was under fascist dictatorship Gibraltar was blockaded, so music represented freedom[11] Eventually British and American music overtook the Spanish and Latin music of the earlier generation. I logged this complex music network via my research in the GBC sound library and recorded conversations between myself and my mother going through these logs and remembering the vast range of songs. As she has a good memory, between us we mapped a music territory. The soundtrack to my film I Die of Sadness Crying For You (2019) focussed on the powerful music of the Spanish Copla genre and the immense sounds of their female singers from the 1930s and 1940s, which were still very strong till the 1970s and 1980s. It died away as Spain modernised but more recently has been reclaimed as a popular genre in Spain today.

I learned how to read literary texts, analyse and to produce literary criticism. One of the revolutionary texts was the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s essay on the ‘Imagination and the Fancy’ (1817), which unlocked important ideas for me very early on. Coleridge lays out the differences between the two – one leads to art or to original complex unifying synthesis and the other is a lesser form which finds its outlet in illustrative, literal and associative forms. The important aspect of this essay is that he explains exactly these routes and argues for them in a methodical and evidenced way that I found totally convincing. It unlocked and informed my method of criticism and analysis of art and of all works, showing how they can be judged critically.

Another important influence was the BBC documentary A Question of Feeling (1970) about The Locked Room experiment, which was televised by GBC, the local television station.[12] The Locked Room was one of the, if not the, most radical and notorious pedagogical experiments in the history of British art schools, where tutors at St. Martin’s School of Art [later Central Saint Martin’s, CSM] locked students in a room and told them to make art, which they also weren’t allowed to keep. Before watching that I was set to study English Literature but seeing the documentary decided it. I was so taken aback by what I saw, the tutors going around with paper bags over their heads and the students not speaking. I felt that I needed to be part of this because it seemed something radical and was totally outside of my sphere of knowledge or understanding of what art was. I was literally awestruck and I wanted to find out what it was about, so I decided to go to art school instead.

Helen de Witt:

Before you started practising as a filmmaker, were you involved in any other art forms?

Nina Danino:

As I mentioned, I went to study at St. Martin’s in London, where I did Fine Art, specialising in Painting.

Helen de Witt:

Could you speak a bit more about this education and training as an artist? Was it what you expected and what were the major things you gained from it?

Nina Danino:

Before starting the BA, I did Foundation. It was there that I was invited to performances that took place in the ‘A’ course in Sculpture (infamous for the Locked Room experiment). They were not wholly understandable and I felt this was part of the interest to me.[13] I then continued to the Painting Department where I studied between 1973–77. In the late 1970s, abstraction was still the dominant style. I made colour field paintings also using household paints. They were in beautiful pastel colours, gloss and matt. Artists Jenny Durrant, Gillian Ayres and John Hoyland were my main tutors over the three years of the course; but there was very little actual teaching. It was more listening to tutors as they talked indirectly about their interests, influences and improvised thoughts on their own painting and social circle. I can see now that it was a radical non-pedagogy, it threw you back upon yourself as an artist. They didn’t really teach anything per se, yet it gave you the key to taking authority for your own decisions. Abstract painting, however, was under critique or even attack from critical theory and conceptual approaches to art which were favoured by Complementary Studies when I was there.[14] There was also filmmaker and artist Malcolm Le Grice’s Experimental Film Unit (which he set up in 1967), housed in the basement of the Charing Cross Road building. The Painting Department was on the upper floors and in part due to this proximity, it was fairly natural that painting students also started making films (such as Gill Eatherley, Annabel Nicolson and William Raban to name a few). I continued in the Painting studios.[15]

Today, looking back I would argue that the insistent Marxist criticism of abstraction and the peer male culture around painting eventually caused me to question painting and I began to find that my painting flow became blocked. I lost my enjoyment of it. However, it was through abstract painting that I found an affiliation with modernist avant-garde film and questions of medium specificity and materiality.

Helen de Witt:

Having discounted painting but incorporating the critical thinking gained from the Foundation, you made your first film, First Memory (1980-81), a slide/tape piece that used Super 8 and 16mm. It was bold in its lack of imagery and use of blank space and was when you started using your voice, which is an important aspect of all your films since. How did you come to make such a complex multimedia work? What were you seeking to convey through this technique?

Nina Danino:

I didn’t discount painting, I rejected it. At the time, I was reading Simone De Beauvoir and other existential writers and playwrights around her like Albert Camus, Françoise Sagan, Violette Leduc and Jean-Paul Sartre. I was identifying with and studying the women characters in these novels. I felt that the philosophical implications of romantic love for women which for De Beauvoir was to be based on ‘authentic’ love and freedom did not deliver freedom to the women characters in the novels nor by the women writers. They seemed to entrap the women protagonists in passive conditions as characters and as women. I took this as a proposal to study the state of femaleness in image and sound when I went on to study in the Department of Environmental Media at the Royal College of Art (after St. Martin’s), which focussed on time-based areas of contemporary media, performance, slide/tape, video, photography and audio.

While studying in the department of Environmental Media I used slide/tape to make the first version of First Memory, I recorded narration and used a graph to keep the sound and images tracked and timed. I inserted blanks to create an interval for reflection and duration, thus no image became part of the work in the slide/tape projection. Since then, I have used black film in some works, most recently, in Solitude (2022). I love black film and have just made a draft film using black and I also wrote essays on black film as a medium of resistance to representation and as a metaphor for visionary experience in Temenos (1998).[16] This created intervals of time for the viewer’s reflection and was most likely related to what I was now reading at the time – objective nouveau romans by Alain Robbe Grillet like Jalousie (1957) and L’Immortelle (1968), which also influenced the films of writer and artist Marguerite Duras as well as schools of structuralist thinking in literature and formal film.

Outside as it were, there was feminist work about gender, identity and social issues but I felt that representation itself was radical. The ontology of time-based mediums, slide/tape and later, single screen 16mm film was important to how I was structuring these thoughts: how one image invited a speculative relationship with the next image and the relationship of image to sound and time and how this was withholding representation or presenting non-representation. I wrote about formal means and female representation in First Memory in an (unpublished) essay at the time, ‘Image and Narrative’ (1981).

In terms of mounting multimedia as you say, it was a process of paring down. The original multimedia two-screen installation of First Memory (1980) included slide/tape, Super 8 and sound. It was only shown once (due to the complexity of the installation) as part of the ‘About Time’ programme of the exhibition Women’s Images of Men at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) London (1980). The final version, First Memory (1981) was a single screen 16mm film and it premiered as part of the New Contemporaries exhibition, again at the ICA in 1981. It was then shown again as part of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative (LFMC) Summer Show (6-11 July 1981). A two screen slide/tape version was also shown as part of the Degree Show at the Royal College of Art that same year, this time comprising only slide/tape as well as the 16mm film.[17] Each time, the installation and configuration of media varied.

Helen de Witt:

Why did you affiliate yourself with experimental films? What did you see there and what was it that made you take up the camera and make film experimentally?

Nina Danino:

I began to learn about experimental film from the students who studied under the artist Peter Gidal at the RCA Film School, people like Lucy Panteli, Michael Mazière, Joanna Woodward and Rob Gawthrop. Artist and LFMC founder Steve Dwoskin also taught at the RCA, and I saw a number of his works around voyeurism. Artists Lis Rhodes (who I also spoke to for this series of conversations) and Peter Gidal were my tutors at Environment Media. Peter Kardia (who I’ve previously mentioned) created a structural and sculptural framework for teaching at St. Martin’s, which he then brought to Environmental Media at the RCA. The pedagogical focus was on attention to the means, the material, the process and formal concerns rather than resolution. However, I did have to apply resolution to First Memory as a time-based work.

At the time I was using slide/tape and the structural novel and ideas of representation of women and already making visually and formally self-aware time-based work. I didn’t have a concept of making First Memory in the context of other experimental films but as a standalone object that attended to ontological time-based concerns, the medium and the form. Part of this engagement with medium involved making a 16mm film from slides, using colour reversal Fuji and there was the excitement of the new medium as well as transferring images from one medium to another.

I think my reason for affiliating myself to experimental film was because it was self-critical, rigorous and free from film standardisation. I wanted to work in a form that I could construct and structure myself, so I moved to 16mm, which was also the medium for experimental film. I was not thinking about it being an experimental film. It was a film.

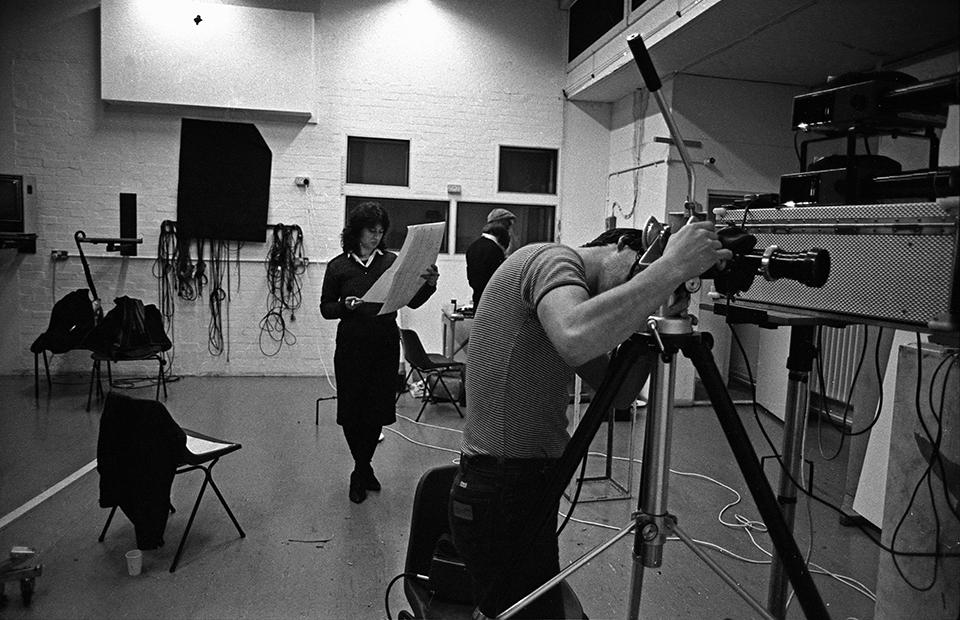

Production

still: Nina Danino (left) with ‘Editing Chart no 3’ filming First Memory on 16mm from slide

projectors in the audio/video studio of Environmental Media, Royal College of

Art (RCA) (1981, London). Ian Duncan (foreground) and Michael Raine

(background) are also pictured.

Photo:

Mirta Alagia. Copyright: Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

Tell us about your experience of the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC], when you first started being involved.

Nina Danino:

I was introduced to the LFMC by Lucy Panteli and Michael Mazière while at the RCA. They very much pointed out that it existed. Lucy Panteli painted a radiant picture of it as somewhere where we could continue with our films after the RCA. It seemed a paradisical situation and I became a member in 1981 or early in 1982, somewhere around the time I showed First Memory at the LFMC Summer Show, which showcased new films in distribution. As well as being a workshop to make film, for me what was important was to go to the cinema and to see films, to have new work shown with other new work. The culture was to attend and support work by friends and colleagues.

When I became a member, the LFMC was in its final home, a building leased from British Rail on Gloucester Avenue in Camden, which they shared with the London Musicians’ Collective.[18] When people say it was a hostile place I think it was the run-down atmosphere of the building rather than the people being unfriendly – the building definitely set the tone of the LFMC. The cinema, as I said, was for me a meeting place but I can see how the building could make it feel intimidating.

At this time, I was also freelancing as an assistant editor at the BBC and in the independent sector.[19] I was making the film Close to Home (1982-85) for which I bought a Steenbeck flatbed, used for editing and viewing film, and set myself up at home, as I was working irregular hours and couldn’t get to the Co-op to edit. This is why it took three years to make. I later did the labour-intensive optical printing of Stabat Mater (1990) with artist Nick Collins at the Co-op. The blowing up process from Super 8 to 16mm on the optical printer was originally scheduled over five days and went on for weeks. Through cinema attendance I got to know everyone there very well – Susan Stein and Pete Millner were the Workshop Organisers, artists Anna Thew and Martin Lugg were Distribution Organisers and the LFMC cinema in the 1980s was variously programmed by Michael Mazière, Cordelia Swan and Cathleen Maitland Carter, whose approaches were quite different.

Later when digital video came out in the 1990s, I used corporate and independent editing suites in Soho on their downtime, mostly through my contacts in film and TV. With facilitation by producer Janet Marbrook, I was able to do post-production for “Now I am yours” (1992) at the studio of Chrysalis Television on Chalk Farm Road (up the road from the Co-op), which was beyond what the budget would have been able to afford. I also used Filmatic Laboratories at Colville Road, a commercial laboratory favourable to experimental filmmakers thanks to Len Thornton who was a laboratory manager. I had to fit in making Close to Home around freelance editing, so I needed reliable technical systems. At the time, I was very split. I saw working as a freelance editor as a job and really, I just wanted to make my films, but (as discussed with Jayne Parker in another conversation in the series), I now look back gratefully at the training that I received as it has been invaluable to my methods of editing since.

Helen de Witt:

As you indicate, this early work was made and appeared at a particularly rich moment in the history of experimental filmmaking in London, the final period of the dominance of structural materialist practice as well as the opening-up of industry opportunities to non-union makers in the 1980s. To what extent did you feel your work as different and how did you find these friends and allies at the time?

Photo of

Nina Danino at the Royal College of Art Degree Show (1981).

Photo:

Patrick Keiller. Copyright: Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

In another conversation in this series, I spoke with Anna Thew, about this. The idea of ‘allies’ in making practice is interesting. Anna observes that there was a judgmental and superior attitude by some second-generation structural filmmakers, making it difficult to situate your work – but not those from the first generation. I agree with her – as I mentioned, I had experienced this already in my painting studies from male peers.

In another conversation within this series, Dutch filmmaker Barbara Meter talks about the ambivalence of our positions as women in experimental film as a male-dominated modernist art culture. At the time, I felt that my work did not wholly fit into the structural ethos due to its subjective voice and use of narration. It was not objective enough. Yet, despite the structural dominance at this time the LFMC incorporated and showed many diverse films and practices. Still, my affiliation was with an experimental structural approach.

Helen de Witt:

The contexts of the LFMC as a network of social interaction were particularly significant at this time, as a woman artist, who were the people that you felt you had most in common with there?

Nina Danino:

What was important to me about the LFMC was that I was able to meet and talk to other artists. At the LFMC we didn’t call ourselves artists but filmmakers. Film was the specific nexus through which we connected and realised our passion. I talked to people like Guy Sherwin, Nicky Hamlyn and Nick Collins. There were also expanded networks and miscellaneous events loosely connected to the LFMC, for example Guy Sherwin hosted home screenings where I met Barbara Meter and Anabel Nicholson. This experimental film culture also mixed generations with first-generation filmmakers, being there and showing their work at screenings, and going to The Engineer pub afterwards (across the road from the LFMC/LMC). John Smith, I recall, commenting wryly in the pub. At Gloucester Avenue I was able to reconnect with friends from the RCA like Lucy Panteli and Michael Mazière and with Jean Matthee from The Slade and Royal College of Art (RCA) Women’s Group, which was active between 1981 and 1982 (and included other artists such as Mona Hatoum and Laura Ford). Filmmakers such as Vicky Smith, Steve Farrer, David Finch, Will Milne and David Larcher were also important. I mention a lot of men’s names but, despite the feminist contexts and theories with which I was engaging, they were my network.

For much of the 1980s I was also a member of the Undercut Collective editing Undercut magazine. The first issue was published in Spring 1981. I joined soon after in 1982 and was involved until the last issue was published in 1990. Although the magazine was subtitled “the magazine from the London Filmmakers’ Co-op” the collective was independent from the LFMC Executive Board. We had monthly production meetings on Saturdays at Gloucester Avenue, creating another circle, among people like the critics Michael O’Pray and Al [A.L.] Rees, scholar Gillian Swanson, artists like Pete Milner, Nicky Hamlyn, John Woodman, Michael Mazière and shorter-term members as well as all the contributors who often became part of the entourage. These were the networks and people through which I engaged with the LFMC – through viewing, screening, discussion, writing, practice and social connection.

Helen de Witt:

You’ve mentioned the importance of screenings and seeing/sharing new work a few times. This was a key part of how the LFMC functioned. What were the films you saw at the time? Were there any which particularly influenced you?

Nina Danino:

Looking back, there were the most incredible screenings at the

LFMC – of historical avant-garde, underground films and new films in

distribution, films by peers and first-generation structural filmmakers. I have

an almost full collection of LFMC programmes, largely the screenings I went to,

as I picked them up there. The ones that stood out for me at these screenings

(and that I remember now) were Cleo

Übelmann’s Mano

Destra (1986), Neon Queen (1986) by Jean Matthee, Nina Menkes’ Magdalena Viraga (1986) and Andy

Warhol’s American underground film, Chelsea

Girls (1966), of which I have a predominantly sonic recollection,

particularly the dissonant clatter and harsh sound rebounding in the cinema. I

was excited to see the camera-centred film News

from Home (1977) by Chantal Akerman, a new feminist visual economy of the

personal. Marguerite Duras’ sensual cinema, particularly the screening of India Song (1975) at the LFMC, left an

impact and I was absorbed by her somnolent, oneiric films. I was utterly

seduced and fascinated by ‘longeurs’ or tedious passages – training us about

attentive viewing. Not to mention properly difficult films such as Peter

Gidal’s Room Film (1973). It was not

always pleasurable. But essential.

Helen de Witt:

It’s interesting to think about how these influences might connect to your practice. Your work is hugely distinctive in the way it integrates your influences, the themes in your films. In Stabat Mater (1990) we see a statue of the Virgin Mary alongside narration of the final part of James Joyce's novel Ulysses (1920), connecting to your early literary interests but also Gibraltar, where it takes place. The film seems to be about a return to a kind of home, but instead of it being a place of comfort, it is found to be disruptive.

Nina Danino:

Yes, it is about disruption and movement to be dynamic and not become a representation that can be fully grasped. Yet it still has to have comprehensibility and unity as a film and not be chaos, so that it can make that jump into the limitless void. It was disruptive and probably unsettling to viewers due to the saetas and religious images. At its premiere screening at the LFMC, the cinema was packed but at the end it was met with a long pause of silence.[20]

Helen de Witt:

Was there any writing on experimental film that influenced or supported your work?

Nina Danino:

As mentioned, I did situate myself within the structuralist canon so to speak. Gidal’s essay Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film (1976) was very influential, as it theorised an objective framework for a materialist film practice.[21] Although concerned with Gidal’s own practice, its insights into presence, time and duration were, in retrospect, foundational to my work.

Much feminist film theory in the 1980s was looking at Hollywood and auteur film and the debates didn’t seem to apply to experimental film.[22] My films might not have been able to go beyond metonymic formalism and negative aesthetics without the influence of structural film and insights into ‘structural/materialist’ theory (to use Gidal’s wording in his essay), through abstraction and modernist avant-garde film aesthetics (rather than poetics).

Filmscans

(16mm) from sequences in Nina Danino, Stabat

Mater (1990).

Copyright:

Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

Leading on from that, given the importance of structure in your work, could you talk about how the unconscious works within your films, and their transformative power on the viewer? How do you want the viewer to be transfixed or transfigured through your relationship with your work?

Nina Danino:

The transformative power on the viewer is rather unlocatable, so no evidenced method can be applied to show how the viewer might be transfixed or transfigured – but the same can be said for Kristeva’s ‘semiotic’ – there is no real evidence for such a register. Such a concept as ‘the feminine’ also eludes representation necessarily. For Kristeva “Femininity and the semiotic do, however, have one thing in common: their marginality. As the feminine is defined as marginal under patriarchy so the semiotic is marginal to language”.[23] The interesting part is how these theories combine with the materials of film and ineffable aspects of cinema to impart a metaphysical experience. This may have been what impacted me when I experienced Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew when I was younger. These elements came together or traversed through one person, a viewer in a unique moment, leaving an impression like a ‘transverberation’. According to the French film critic Henri Agel, cinema is already religious through the potential of impression. For Henri Agel the spiritual potential of cinema and what he calls the soul is in all aspects of the conception of the film. As Sarah Cooper writes, “from its inspiration and its production through to its interpretation. It is neither unlocatable nor locatable in representation but manifests itself through the impact on the viewer”.[24] The transformative or transfixing power comes from the material of film and the potential impression in cinema.

Helen de Witt:

A materiality, 16mm became your primary medium for many years. What was important about 16mm? What did you particularly enjoy about working with this medium/gauge?

Nina Danino:

What I most enjoyed about working with 16 mm was editing on the Steenbeck. I enjoyed the rhythm created to establish pace and the moment, the frame of the cut. This was part of the choreography of the body and the machine. I felt a bodily engagement with it. Both First Memory and Close to Home are Steenbeck-structured films. In the 1990s with formats such as VHS, Beta Sp, Digi Beta or Hi8, my editing moved to offline. I did a 16mm assembly edit of the silent film Sorelle Povere di Santa Chiara (2016) on a Steenbeck for the pleasure of revisiting the pulse of mechanical editing and handling celluloid.

Helen de Witt:

This sense of structure in many ways creates the atmosphere in your films in incredible and unexpected ways. “Now I am Yours” (1992) is an ecstatic religious rapture inspired by Bernini’s Saint Teresa of Avila statue in Rome, juxtaposed with gorgeous, coloured flowers and baroque interiors, which hold us as if displaced from the earth into the heavens. The sound-music and voice are incredibly powerful. How did you bring together all the elements within the film to create such a transfiguring experience for the audience?

Nina Danino:

The master footage of Bernini’s statue, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa was filmed in black-and-white on 16mm at 24fps at the Cornaro Chapel in Rome. It is unbelievable that we were able to film in the Cornaro Chapel. It was an unforgettable experience. In “Now I am yours” I didn’t know if it would be possible to create a dynamic construction just with the 16mm. It wasn’t. My impulse was to bring the figure of Teresa to life from the stone where, I felt, she was trapped as a woman. However, at that time, I saw her as a writer rather than a mystic because I was strongly atheist. This ‘resuscitation’ was a drive because it was also about mourning and death. There is a lot of burial in the film and the impulse to ‘bring alive’. The way to this resuscitation was through the mixes of S8, Hi 8, VHS,16mm, Beta Sp and extracts from the 35mm film Teresa de Jesús (1962) in the completed film. I feel it is all these together that create the mystical ecstasy and the body of the film. To me, this was subjected to the inscriptive drive and the textual body of St. Teresa and are networked and part of this body. Theoretically, it mixes the semiotic, psychoanalysis, mystical Christianity, materiality and dialectics to create the transfiguring experience. The film is founded on the study of St. Teresa’s mystical writings and on knowing the material frame by frame. I recite St. Teresa’s writings in a mode of reading/speaking accompanied by layers of voice and wordless vocals. It was new to invite a saint into this self-inscriptive experimental film.

Production

photo showing Nina Danino and (16mm) cinematographer Christopher Hughes filming

“Now I am Yours” (1992) in the

Cornaro Chapel, Rome in 1991.

Photo:

Monica Zanolin. Copyright: Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

In The Silence is Baroque (1997) there is a cacophony that includes sounds (men talking) from Pasolini’s film Accatone (1961) with location sound recorded during Holy Week processions in Andalucia. This film seems to be about combining the energies of life with the mourning of death. How did you approach combining such elemental human forces? As well as S8 you also use the Hi8 video in this film, what were your reasons for that?

Nina Danino:

The Silence is Baroque is one of the three self-inscriptive films. The films are fast paced in editing, combining voice and image. After I made Stabat Mater the others followed in editing style and involved a dynamic relationship of image to sound. It is a procession film shot in Granada and Seville. I wanted to get in amongst the crowd, to be part of it, and Hi 8 and Super 8 enabled this as both are light cameras. I had a sound recordist with me, and we roamed through the processions and the streets. It is the music and the crowd that supplements the enfolding collective jouissance and this is what I tried to immerse myself in and to capture in the film. Today I probably would not include the speaking voice but use more of the wonderful music we recorded on the street. I may make a new version or another procession film.

Production

photo showing Nina Danino (pictured on the platform) filming “Now I am Yours” (1992) in the Cornaro

Chapel, Rome in 1991.

Photo:

Monica Zanolin. Copyright: Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

Can you tell me more about your journey from discovering your desire to practice as an artist to realising that passion? What about the auto-biographical elements and what you term ‘self inscription’? Why is that so important and what was particularly significant about being a woman artist doing this?

Nina Danino:

I think, being a woman gave me the foothold into my main ideas, representation, the subjective, excess, surplus, ecstasy and jouissance.

Helen de Witt:

Did you have any significant literary or philosophical influences, perhaps in terms of psychoanalysis or feminism?

Nina Danino:

I was introduced to Carolyn Gill’s ‘Time and the Image’ seminars by Jean Matthee. I attended from 1990 until 1998 on and off. This gave me important study continuity when the Co-op was not functioning very well. I also contributed and presented my work. The first year introduced French feminist literary theory by people like Kristeva, Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous and it was groundbreaking for me.[25] Because of these influences, in the 1990s psychoanalysis and a different notion of the subject and woman entered my work and the aspects of jouissance I was exploring. Feminist literary theory and French feminist writing ultimately enabled me to depart from formalism and the negative aesthetics of First Memory (1981) and Close to Home (1982-85) to the euphoric verticality and completely new visual experimental film language of Stabat Mater (1990) and “Now I am yours” (1992).[26] I attended many conferences, events, talks and discussions on psychoanalysis in literary criticism and film studies. I also took part in the ground-breaking conference Psychoanalysis and the Image, where I showed “Now I am yours”.[27] However, on the whole, psychoanalysis was not really favoured in experimental film circles – only Michael O’Pray wrote on it in relation to avant-garde film.

For me, psychoanalysis was vertiginous and fascinating and a new step into understanding the subject through ideas of the drive, jouissance, concepts of plenitude and loss and ‘woman as a blind spot’ or ‘lack’ in the signifying system – a place to fill with fullness. These concepts were no longer filtered through stable observation but through an unstable subject of emotional energy, pulsion, rhythm and other forces beyond language. I would not say pre-verbal exactly, which seems to imply regression. As mentioned before, I was favourable to Kristeva’s concept of the semiotic as a pulsion in literary theory, transposing it to experimental film. Lacan’s concepts of the phallic and mystical jouissance were exciting, which I mixed as one.[28] Thus, these co-joined around experimental film as a unique place for the feminine as the subject of creation and interdeterminacy, instability, improvisation, structure and heightened register.

Texts on the relationship between psychoanalysis and cinema were naturally important. The art critic Rosalind Krauss threw light on the male modernist vision machine of avant-garde film. Kaya Silverman explored the maternal and woman’s voice in cinema, which was elucidating.[29] Even though I had already formed my own idea of the voice to counter the notion of a male voiceover. I also read male writers on the voice as an object in cinema but they resonated less with my interest in the woman’s voice and the language of experimental film.[30]

In my practice and research at this time I mixed literary theory and psychoanalysis with ideas relating to experimental film. Stabat Mater mixed experimental structuralist aesthetics with the textual rhetoric of James Joyce’s modernist novel Ulysses (1920), adding Cixous’ concept of ‘ecriture feminine’ as poetic writing – where the subject is speaking from a place of plenitude.[31] Kristeva’s notion of the pulsion of the semiotic and Lacan’s feminine circulate in “Now I am yours”, and of course, in my filmmaking I connected the religious as a heightened discourse with these feminist frameworks. I was creating my own unorthodox mixes of these theories: the films intended to generate and perform their own theory.

Helen de Witt:

Communion (2010) is a study of a young girl in a first communion portrait. Can you talk about how it's filmed, in beautiful, textural black-and-white?

Nina Danino:

The cinematography of Communion (2010) is by Billy Williams, who worked on the opening sequences of The Exorcist (1973), Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971), Women in Love (1969) and Gandhi (1982), filming Hollywood stars including Lana Turner, Jane Fonda, Elizabeth Taylor and others, which was integral to my approach in this film.[32] It was shot on 35mm using Hollywood 3-point light in the manner of the portraits of stars. It was filmed in the neo-Gothic church, Our Ladye Star of the Sea in Greenwich just before Christmas in 2009. The location had significance, as my daughter, Thalia Somerville-Large had her First Communion there six months earlier. The church also has interesting architectural details, including windows by A.W.N. Pugin and E.W. Pugin in the interior, which lent themselves to exquisite lighting by Billy Williams.

Communion was made as a new work for the exhibition From Floor to Sky, curated by Peter Kardia.[33] Exploring ideas related to the art studio, Communion was shown in the exhibition together with a re-installation of the First Memory (1981) slide/tape, which I had made as a student of Kardia’s at the RCA.[34]

Production

photo, shooting Nina Danino, Communion

(2010).

Photo: Jane

Atkins. Copyright: Nina Danino Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

In Communion, we are first drawn into the image of contemplation and quiet coming up before naturally, the girl starts to look a bit uncomfortable and fidgety. This is an amazing way of joining the ancient and modern, particularly in terms of gender. Can you tell us a bit more about the process of making the film?

Nina Danino:

When I had my Communion in the 1960s, I had my studio photographic portrait taken and like every other child’s, it is sublimely beautiful. I wanted to achieve extraordinary photographic beauty in a film study but to push it to its limits. Technically, it is the same system of lighting as traditionally devised for the face of a star in Hollywood. The Communion portrait draws on the metaphor of light to represent the transition from innocence to a life of conscience in a child of around seven years which is the meaning of the sacrament of Communion. My film also references transfigurative moments in cinema portraits of young actors’ faces, such as Renee Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) or the actor Jennifer Jones in Henry King’s The Song of Bernadette (1943) – both involving highly religious, canonised female historical figures. I’ve returned to the portrait and subjects during casting for my current project, The Far South (forthcoming), as these types of portraits also echo the format of the screen test (when actors audition for parts on-camera), an experience that is itself a threshold, but where innocence transitions into the profane. Thus, the themes in Communion as a study will migrate to secular discourses of the face, albeit with a theological framing.[35]

Holding the poses under the lights caused the young subject discomfort and the intense conditions of production bearing down upon a young girl are also foregrounded by the film shoot and point to the profane, sacrificial, oppressive, merciless and even diabolical system of Hollywood 3-point light invented to produce allure and surface beauty.

Helen de Witt:

Apparitions (2013) – like the phenomenon itself – exists in different versions depending on the exhibition context in which the film is shown, possibly because of the flexibility of shooting some of it digitally. It has a feeling of spontaneity about it. Can you talk about how the camera is used to investigate each image to which your own voice responds. What was it you were seeking to draw attention to or to bring together in these Apparitions?

Nina Danino:

What was my investigation? The photographs themselves. I was just using the mini DV camera to probe through the act of looking. The film examines a set of photographs from my childhood, taken on local beaches, considering the impenetrability of a photograph and our inability to grasp it.

The subject of looking through the lens intensively was also discussed in my email exchange with Lis Rhodes, in our discussions of her film Light Reading (1978). The act of looking through the camera becomes a means of probing, of remembering or trying to see: to acquire vision – also discussed with Barbara Meter in another conversation in this series, in relation to the optical printer.

When shooting Apparitions, I was improvising and speaking my thoughts aloud as I filmed this impenetrability.[36] In the video soundtrack, we hear a voice calling out ‘Marcello’ (Mastroianni), taken from La Dolce Vita (1960) by Federico Fellini, which was made at around the same time as the photographs were taken, on another beach, but in the same elemental geography. The voice is drowned out by the sound of crashing waves. Beaches mark boundaries and are liminal thresholds.

Helen de Witt:

Sorelle Povere di Santa Chiara (2016) is a naturalistic, observational, perhaps even ethnographic film about the nuns of the Poor Claires of the Monastero di Santa Chiara, San Marino (Italy). How did you adapt your filmmaking style to make this film?

Nina Danino:

Sorelle Povere di Santa Chiara (2016) was my coda to Roberto Rosellini’s film Little Flowers of Saint Francis (1950), which it references in the graphics. Rosellini’s film is about Saint Francis’ band of monks. Clare, the founder of the Sorelle Povere appears only once in the film. Francis and Clare have a meeting in a field. The scene is deeply beautiful, but I wanted to give Clare, the founder and the sisters their own space to speak through the centuries. This is the only scene in which they appear. The Franciscan monastery was also situated next to the new Monastery of St. Clare in San Marino, where I filmed and stayed. Although they are autonomous, my impression was that the Franciscans are their spiritual directors, much as Francis was Clare’s. The Franciscan ideals of simplicity, the Highest Poverty and work of the hands are transferred to the filmic medium used. The Bolex camera and composition create a sense of serene stillness in the depiction of the sisters pursuing simple crafts and household duties.

Helen de Witt:

Crying for you day and night (2021) combines the opening scene from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) with the rock music of the band Deep Purple. It's a stunning experience. What led you in this direction?

Nina Danino:

I’m singing the rock anthem, the song Child in Time (1976) by Ian Gillan, lead vocalist of Deep Purple. He was known for his high screams and falsetto voice. It felt empowering to do. It was professionally recorded in the music studios at Goldsmiths University with other covers.

Helen de Witt:

This musicality is of course significant to your practice. In terms of structure, your films don't have linear narratives as is commonly understood, but instead swooping, looping or folding structures. This holds, perhaps with some exceptions, in your feature-length work as well. How do you go about conceptualising structure and then realising it through your editing?

Nina Danino:

I think about the trajectory itself as the narrative and how it builds up towards a climax or several heightened points. I thank arts producer Gary Thomas for once writing in a letter how he thought I could command structure to create emotional impact.[37] That’s just it. Structure is needed to create the flow and build of emotion which is the trajectory. The process of building a climax when there is no storyline is like building an intensity across time while building pressure behind and on the image, but also through the sound which can be silence or pauses. There are also other factors like pace and rhythm. I have used chapter structures in some films. In other films, it is a structural concept. Stabat Mater is structured like an altarpiece and MARIA (2023) is like an iconostasis. I also use schemas; I need to see them visually. There are large wall charts for Temenos and “Now I am yours”. As seen from the earlier image at the RCA, First Memory was plotted in graphs. Now I use digital templates, keeping everything in a relational place otherwise it would be impossible to structure and create a trajectory towards intensity in a long film.

Film Still

from Nina Danino, Sorelle Povere di Santa

Chiara (2016).

Copyright:

Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Helen de Witt:

This intensity is also closely connected to your use of voice. Your voice is critical in all your work. It provides a narrative, a counter-narrative, a commentary, an incantation and many other functions. How and why did you decide to make your voice such a crucial element of your work?

Nina Danino:

In First Memory I wanted

the single voice to be on the edge of reading/speaking in a neutral tone. I

wanted to keep out characterisation. The narration is spoken at a deliberate

pace and delivery. I wanted to convey sensuality. I wanted the closeness of the

voice to the microphone to give it a sensual intimacy and physical presence.

This was important to enunciate a female presence because the woman’s voice is

always connected to the body. I continued a measured recitation in the next

film Close to Home (1982-85). I drew

a clear difference between my idea of the voice not being a voice-over, which

Silverman theorises as a male dominant structure in cinema (mentioned earlier).

The woman’s voice territorialised the woman-centred work I was doing.

Helen de Witt:

In later films we hear you singing. Why did you decide to go from the spoken to the musical voice?

Nina Danino:

I started in 2020 and it was a slow need which built up and took me in that direction. During the pandemic, I took vocal lessons and did some courses online and later took night classes with different vocal teachers, including one exploring the Early Medieval plainchant of Hildegard von Bingen (with mezzo soprano and troibaritz Maria Jonas). [38] I just felt I needed to follow this expressive channel to new experiences. I felt it more and more and it opened itself as a path, leading to my recording the improvised sound works Gethsemane, Vision Eleven, Puer Natus Est Nobis and other try outs.[39] I also started work on covering the songs by Nico, the lead singer of the band The Velvet Underground, which became my film Solitude (2022). The voice has turned out to be the most important part, in a way it is turning out to be my centre.

Helen de Witt:

What is your approach to sound composition and arrangement?

Nina Danino:

I like to combine different genres of music with spoken words and

vocals. I’m not listening to the genre but to the feeling. This might lead to

unexpected combinations, for example, rock music by The Doors is included in MARIA, a film about opera. The Spanish

saeta in Stabat Mater is used in its

tight traditional form but in the next film “Now

I am yours” I wanted to break out of the song form – to what might be

termed ‘the voice of the film’, which are all the elements brought together. I

didn’t know what this would sound like or if it was possible. I felt that the

vocals, spoken word and any other elements should come together to form the

voice of the film. Finding the vocalist to combine with my spoken voice was a

major part. It was fantastic that Shelley Hirsch performed in “Now I am yours”.

The cry and scream are also very much in my work as the subject in extremis, from soprano to contralto. Singers like Diamanda Galas and Sainkho Namtchylak, Nico and Maria Callas are exciting performers because they can go to extremes. I enjoy recording with musicians and there is an alternative version of the MARIA soundtrack, re-interpreting the soundtrack to Pasolini’s Medea (1969). This version includes recordings by musicians and singers of folkloric, sacred and ancient chant traditions. [40] As I discuss with Johanna Blair in the interview on ‘The Myth and Cult of Maria Callas’ this also connects to my parallel interests in literature, in both MARIA and Solitude “I am presenting icons and I enter the domain through the reading of poetry.”[41]

Photo

showing the recording of an alternative version of the Medea soundtrack (originally directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini,

1969), which was then used as the soundtrack for a version of MARIA (2023) by

Nina Danino. St. Catherine’s Church, New Cross, London, September 2023. Sound

recordist James Bulley (left), Tanpura player and Carnatic singer Yarlinie

Thanabalasingham (centre), Nina Danino (right) are pictured.

Copyright:

Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

Like many moving image artists, at a certain point, you moved from 16mm to digital filmmaking. You’ve mentioned this transition earlier, but what were the reasons for this? How did it make you feel about your practice and the work itself?

Nina Danino:

It was a breakout point for me to mix formats in the films of the

1990s and it is the hybridity that was important. It is still a 16mm film

because “Now I am yours” was

telerecorded (as it was called) to analogue but the offline editing allowed a

fluidity that was very much in keeping with the ‘feminine’ register as a kind

of ‘ecriture’, following on from Cixous’ writing. I use this term as way of thinking about

a form of making, which I then transpose as a ‘feminine’ register of fluidity,

plasticity and elusive instability of the materials in the construction of the

work.[42]

At each transfer of “Now I am yours” the images deteriorated and faded further, almost

to the ‘noise’ in the image. These offline tapes are quite beautiful now.

Offline and different formats enabled a performative plasticity, an aesthetic

surface and texture that 16mm and the Steenbeck would have been too stable and

rigid for. It allowed me to break free of the Steenbeck and its formal

constraints, which was my reach for the films that came out of that rupture. It

was the 3-machine U-matic edit suite – which crucially had a microphone – that released

the impulse of the film Stabat Mater.

Later it was transferred into 16mm film with all its energy captured. It had a

complicated production process going through the optical printer, although it

looks improvised and immediate, it isn’t. There is a ‘master’ film gauge set

for each film even though it might include different formats. It all has to be

integral and unified, not a collage or bricolage. Temenos is a 35mm film although it has other formats in it. Some

films are one gauge, Communion is 35mm

and Sorelle Povere de Santa Chiara is

photographed on16mm. These choices are part of the film. In this way, the

‘master’ gauge is the language of the film too, but it doesn’t need to be

literal. I embraced the possibility of video and digital but as a means to an

end. I did have difficulty when digital started to be called ‘film’. I know it

is all called film now, but in many ways, the interview series of which this

conversation is a part, has been about exploring that lacuna.

Helen de Witt:

As we’ve touched upon already, the dominant theme of your work is devotion. This takes many forms and is complex in itself. The early films present religious devotion, but also devotion to beauty and shared experience. Your later work explores personal passions and loves, for individuals and arts. Can you say more about devotion?

Nina Danino:

I don’t think of the theme of devotion per se. Experimental film to my mind is not associated with the observance of devotion because it is a disruptive form, and devotion suggests a meditative and attentive approach. However, it is making me think as to whether devotion can also be expressed as something fervent and passionate. In I Die of Sadness Crying for You (2018), the performance of emotion in the songs can be close to religious exaltation – Marifé de Triana is a ‘grandissima’. I show adulation for Maria Callas in MARIA and a meditative devotion to Nico in Solitude – thus they become icons through my film devotion. In Sorelle Povere di Santa Chiara (2016) I wanted to show my devotion through attention to composition. The year before, I made the film Jennifer (2015), exploring the life of Jennifer del Corazón de Jesús, a Discalced Carmelite nun. [43] It is documentary in the interview with her but structural in the filmed interiors as the static camera creates a feminist devotional space within the monastery, especially in the last scene, where the community are praying the Divine Office in the Oratory. The scene was filmed by Jennifer herself – she turns the camera on and walks into the frame she takes her place with the others and joins the prayers. I think it becomes devotional at that point because it is a connective act between the viewer and the community through the duration of the scene which is long and the performance of prayers as well as Jennifer’s own inventive devotion to the film in realising a recording of the community in their inner sanctum, which also is a disruption because it contravened the expressed prohibition of the community on filming them, much less in such an intimate act of prayer.

Helen de Witt:

Another important aspect of your films is beauty. Your works deal with beautiful things, but perhaps sometimes with damaging impacts – such as promoting repressive or gender-stereotypical notions of Catholicism. How do you incorporate things of physical beauty that simultaneously connote things from another realm or imagination, some of which may not always be positive?

Nina Danino:

I can’t see how beauty can be repressive unless it is the perfection of a Chanel perfume advert or a fashion commercial – that is not beauty. Beauty is about imperfection and disturbance, but it doesn’t fetishise it or commodify it. I’m not sure I understand anything about beauty or its pros and cons – I am not sure if my films deal with beautiful things. They are made with such low budgets and so much struggle that their flaws are clear – they are made not in the stables of luxury art nor artists’ studios of productions for galleries and museums but in adverse conditions. They come out of struggle and if I create something that despite all these deficits presents windows to something that can be beautiful – well, maybe it is not beauty, it is something else because their foundations, based on struggle, are there. The dialectic of production is there, I think it has to be there to create something that is not just the lure of surface luxury.

On the other hand, there is a lot of beauty in experimental film obviously, due to its relationship with and dependence on, aesthetics. Gidal’s films in particular. Like other experimental filmmakers, I am also trained in aesthetics, in painting and that permeates experimental film.

Catholicism has strong aesthetics also and as a discourse it enabled me to proceed into a heightened register once I realised that I couldn’t get further in the secular models of literary-critical analysis, continental feminism, post-structuralism and psychoanalysis etc. I was seeking a new discourse that could take me higher so to speak. Catholicism holds many of my sources of art, painting, music, theology, writing and cinema. Andrew Greeley’s book The Catholic Imagination (2000) argues for a Catholic consciousness being deeply immersed in sensuality and sexuality. [44] At the same time, Catholicism is also non-hierarchical and does not differentiate between high and low art forms, simple hymns and sublime sacred music, popular devotion and high Mass – kitsch doesn’t exist. It is messy and includes cheap and precious materials. It is extravagantly iconophile, which is very contemporary, and seeks transfiguration. It has a global spread and a slippage of boundaries between life and art and a rhetoric of abundance. Although, I am indebted to the style called ‘structural film’ with its over-sparse and austere form, which has supported feminist forms, and to some of its claims of spiritual progress,[45] my instinct at present is to follow a rhetoric of abundance especially via the auto-inscriptive aspects of my practice.

Helen de Witt:

Although you appear on camera in later films, in the earlier films do you see yourself as a character or a subject in your films?

Nina Danino:

I was against the idea of characterisation such as in the use of performers or actors in vision or spoken word and theatrical norms of self-presentation because it is a high-level signifier and thus can be an illustrative form of representation. I was constructing a female subject that has no direct or fixed representation or resists representation and different degrees of totalisation and thus rather than illustrate it, to bring it into being, to adopt a use of Gidal’s terms.[46]

In the conversations published here, myself and the other artists I have interviewed have discussed our work through the subject/ive, which we searched for in our filmmaking. The subject isn’t something unified and easy to locate, it is always dispersed and deconstructed, so I think of the subject not as myself, but as an enunciation that comes into being from the film.

Helen de Witt:

How did you begin to see film as a form of self-inscription and personal filmmaking? Was it through autobiographical literature or the tradition of self-portraiture in another form?

Nina Danino:

Self-inscription to me has to do with being in the place of speaking of film, there being no individuation in this enunciation, it is a being at one with the film, of enfolding, of putting yourself in a place, in the place of the film’s enunciation. Becoming film. The camera disappears and there is no observer anymore, but this is the filmic jouissance produced through this process. It replicates or perhaps is itself, a mystical state, it is both undifferentiated and theorised. That’s how I felt making the films. Only the films in the Religious Trilogy perform this mode of self-inscription in my work. I can perform it again, but I didn’t want to repeat it and thus reduce it to a style. When the right film comes, I will use this visual language again. I think self-inscription is something particular and specific and it is not possible with an objective or positional camera.

Helen de Witt:

Do you have a concept of this intersection in your work and how you inscribe yourself in your films?

Nina Danino:

The films Stabat Mater, “Now I am yours” and The Silence is Baroque are published in the Religious Trilogy: Rupture, Rapture, Jouissance DVD, following an impulse to jouissance, trance, transport and psychedelia, where the borders of your body disperse, in this case, in film. It is done through the materials themselves; editing, voice, image, camera, what is recited or narrated – song, location, light, view, pace, rhythm etc. It all has to be confluent and intersect in the right way. If one of these is out of enunciative alignment, the structure collapses and inscription doesn’t happen. But it comes together in the Trilogy, the only films I’ve made in this mode.

In “Now I am yours” I was very clear that I was approaching the saint and mystic not as a unified biographical or hagiographical subject but as an expanded textual production. That I am, as an artist, enmeshed in this expanded network, in photographs, readings, the choice of texts, the personal pronoun. I am enfolded and networked as part of the textual materials. I talk about the film and the fold and this enfolding in Susanna Pool’s The Touching Camera documentary (1998) and in “Now I am yours”, as well as the essay ‘Film, The Body, The Fold’, which I co-authored with Susanna Poole, included in Jackie Hatfield’s Experimental Film and Video Anthology in 2006.[47]

Helen de Witt:

Some women artists such as Maya Deren and others decided at a certain point to move away from appearing in their work and turn to more objective forms Where do you stand in the process of minimization of personal identity in your work?

Can you speak about self-inscription in your films. What does this bring to the work, and do you feel it has changed you as well?

Nina Danino:

The self-inscriptive films are intense and liberating. I don’t believe I was ever trying to create or find a personal identity through my work. I consider identity to be the thing you have to get rid of, thus undoing yourself through avant-garde art. I think it’s the thing that makes something not be avant-garde if I can put it like that. In “Now I am yours” I am mapping myself to St. Teresa as a construction – both of us. The films are part of me, and I am part of them but making films has been a way to find out about film not to find out about myself. The fluid identity that I have created for myself in the self-inscriptive films is not burdensome, on the contrary, it has been self-liberating through the surplus created by the performance of expression. I have increased rather than minimised my presence, so I am probably thinking that more self-inscription is necessary.

Helen de Witt:

How would you differentiate your practice of self-inscription from that of say Chantal Ackerman, Maya Deren or VALIE EXPORT?

Nina Danino:

I consider the personal mode of these filmmakers to be self-staging rather than self-inscription, in the way that I think of it. In my work I am also using other means and media to inscribe myself.

Helen de Witt:

In some films, you use archive footage, particularly of the films of Pasolini and Fellini. What do these scenes add to your work and how do you see them as being re-presented through it?

Nina Danino:

Only very few films that have left such a significant impression on me, and I want to include them in my work. The footage from Teresa de Jesus by Juan de Orduña (1961) is from a generic biopic on St. Teresa and is in my film. In Orduña’s version she is seen in certain dramatic actions personified by an actor, so the film is not charged in the same way. Barthes uses the term studium for what is legible study through standardisation.[48] But it doesn’t have to be an iconic cinema film, any material including television shows can become charged or not. It depends on how it is situated and framed in each case.

In the case of iconic

cinema, film rights owners have to approve the presence of these scenes and be

sent the film at a near-final stage. It is something very big for my film

because these films are cinema icons, and they are not being used as clips in a

documentary to illustrate but as art in art and they also become part of my

film.

Helen de Witt:

Developing your notion of self-inscription, in your later films, you appear on-camera more often. Sometimes this is to lead the viewer into the realm of the film, as if through the looking glass, at other times you are the central performer yourself. Tell us about how you decided to figure yourself within your work in these different ways.

Nina Danino:

My notion of self-inscription is less to do with appearing in the film and more to do with how the film itself enunciates. In I Die of Sadness Crying For You I am being a guide taking you through the film because it is an essay film. In MARIA (2023) I am walking in Maria Callas’ footsteps along the Seine – as she does in the memoire written by her, which I am reciting. Then I step into the film itself in the portraits taken at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. I am more than a guide, I put myself in the film’s frame. I think I wanted to start the process of performing and appearing on camera.

Helen de Witt:

Temenos (1998) was your first feature film. Following that you made Jennifer (2015), I Die of Sadness Crying for You (2019) Solitude (2022) and MARIA (2023). What took you into longer form feature filmmaking? Are these films individual projects or do they have common themes or methods?

Nina Danino:

It’s the medium of time that I love. To set out ideas and to measure, to create a reflexive experience of viewing in some films is important. Time is scale and in Temenos I wanted to work on a larger scale and in a slower time after the fast self-inscription films. I’ve mentioned how the use of real-time in Jennifer creates devotional space and also is an act of trust. It enables the viewer to join them in their real devotional time, to be in their duration as an act of community-building with them. In this way, real time can open routes to a woman-centred and even feminist duration. In I Die of Sadness Crying For You, time is needed to perform the song in full – this is the creation of feminist space, which is being claimed and it is needed also to convey the full emotion of the performance and thus also honour the central performers, Spanish singer Marifé de Triana and my mother. Thus, these decisions make a film longer. Also the feature length is an industry form which is male director dominated and there’s something relevant about that too in using this form in films that are marginal to this and woman-centred.

Helen de Witt:

Temenos certainly takes your work in a different direction in in terms of inscription – it is about the presence of absence. How did you create this powerful work that combines abstract presence and signified absence? How did you make them function together?

Nina Danino:

Yes, after the self-inscription of ecstasy in “Now I am yours” Temenos is landscape camera film. How to create heightened perception was very much at the centre of Temenos. In this film, listening is enhanced by insignificant sounds, quietness, the rustle of a tree, the sound of a bee, and small things which disturb outward normality. The film depicts the cycle of the seasons. There is a slowing down of our senses and this enhances and clears the frame for something else to appear. All these elements are creating the world of Temenos as the presence that we tune into through a sense of cinema.

Helen de Witt:

Temenos is a breathtaking film in many ways. Ostensibly tranquil, but haunted. The landscape carries meaning beyond its mere physical geography – the pain and sorrow of generations past, particularly women. The music is also breathtaking, with sounds that it is hard to comprehend and place but that penetrate the soul. Please tell us about this film.

Nina Danino:

This film is founded on a study of the phenomenon of Marian apparitions in Europe. These apparitions are reported supernatural appearances of the Virgin Mary a few are officially recognised and approved by the Catholic Church. There are many reports that are considered false, which can sometimes be referred to as the work of the devil. Where there is transcendence there is darkness.

The film shows a woman praying at the site of the first apparition at Medjugorje, marked by a pile of stones. The Tuvan throat singer Sainkho Namtchylak sang a deep moan of grief or Houwa (as we titled this track). The woman is like a Dolorosa or ‘woman of sorrows’ at the foot of the cross and also an archetype of the grieving woman, found all around the Mediterranean. It was a manifestation in itself to find her there. I found manifestations in all the landscapes of Temenos, a film in which the landscape is haunted.

Still from

Nina Danino, Temenos (1997). Photo: John Somerville-Large.

Copyright: Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen de Witt:

I Die of Sadness Crying for You is a deeply personal project in that it includes footage of your mother singing. It takes the female voice as an elemental communicator of emotion that resonates beyond its time from the past into the future. It looks at the lives and performances of the women of Copla, a form of Spanish song usually about unrequited love, tragedy and suffering. What took you to this extraordinary place and how does your mother fit into that?

Nina Danino:

To talk about I Die of Sadness Crying For You is to talk about my mother as the source. I have touched on it in other questions. The research for this film took seven years and it has many layers, it would take the rest of the interview to explain them all. However, just to say the deep source is my mother’s voice in singing and her repertoire, which is part of my memory of the songs. There are several songs by my mother (shared on my Soundcloud and other platforms). The Eleven Copla Songs album can be found on Spotify and other platforms. This album includes some of the songs in the film soundtrack as well as other well-known coplas interpreted with subtle feeling and emotion.[49] If you listen, you will hear and understand everything there is to know.

Helen de Witt:

It would be good discuss your recent feature film MARIA. It explores the opera singer Maria Callas – actually moving beyond Maria Callas: it’s like you use her as a totem to investigate wide-ranging areas around women's creative practice and the toll that it can sometimes take on the artist’s identity or subjectivity.

Nina Danino:

I don’t know why I gravitated towards Maria Callas, perhaps

because she is an extreme singer and also lived an extreme life. She is a

sacred monster and a fascinating woman and plays Medea in Pasolini’s film

version of Medea (1969).

Taking on Maria Callas is a big deal – a big beast – I felt it could have sunk me, and I wanted to see if it would and to see what kind of film I would make about such a supercharged icon. I was just responding to her not trying to tell her social story or investigate anything. It was pure allure. I know you have to couch it to funding bodies with research questions and social outcomes but in reality, I was just drawn to Maria Callas as a talismanic figure, to her talent, beauty and work ethic. Her glamour and all these things pulled me towards her like a lodestar. She also has a similar metallic quality of speaking voice to my mother. Then once in her orbit, of course, I read and studied and listened, but I didn’t start with the idea of making an objective study or investigation. I operate more or less intuitively through the drives and in fact, ‘Piercings’ (referring to the piercing cry and scream) was the original film title for the film in an early treatment written in 2009, which was intended to be an expressionistic flow resembling “Now I am yours”. I don’t have underlying questions or themes that I want to tackle in my films. I’d just give up filmmaking if I did. It would not be interesting to me. I’m resistant to this. I am driven towards each film.

Still

showing archive footage of Marifé de Triana in Nina Danino, I Die of Sadness Crying For You (2018).

Copyright: Nina Danino. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Helen de Witt:

You approached the subject using unique archival footage, recorded interviews as well as material originally from television and Pasolini’s film version of Medea. How did you go about finding these rich sources?

Nina Danino:

The film includes performances by Callas in opera rehearsal, recitals and opera performances and scenes from Pasolini’s Medea. There is limited footage on Maria Callas performing, these are well known performances, they circulate in many documentaries.The difference is that I used fragments of this archive to transform them. What is unique is the spoken transcript which I recite in a long monologue in my film. To transform the footage I used optical techniques that relate back to the optical printer and workshop facilities at the LFMC, intercutting negative and positive, solarisation, superimposition, the use of colour filters, re-framing, open scan framing and slow motion. I wanted to return to the orbit of the LFMC using these now classic experimental techniques as they have become. I felt that these would be the route to Maria’s transfiguration. The technique has a purpose, and I had to wait for the right film to use them (I didn’t need to use them in my other films). These techniques forge transfigurations from existing archive images of Callas. The intercutting, flashing and strobing, the flicker of Tosca enhances the demonic aspect of the stabbing and Callas’ rage. The technique of the flicker refers to other experimental films such as Kurt Kren’s White/Black (1968) and its violent optical, shattering and energising effect.

The filming techniques used

for the Paris footage, which was shot on 16mm, were inspired by Stan Brakhage’s

The Dead (1960), which he also filmed

in Père Lachaise and on the Seine. There are shots of Kenneth Anger in a café

in flashing images, with fast intercutting of black-and-white negative and

positive. Through The Dead, I was

able enter the gates of the cemetery of Père Lachaise physically and filmically

– MARIA is, in this sense, a classical experimental film.

Helen de Witt:

As you say, the film ends in Père Lachaise cemetery, and we hear a memoire that Maria Callas wrote about a day when she walked there, we hear The Doors’ song The Changeling (1971) on the soundtrack. Can you talk more about how you set up this scene?

Nina Danino: