Part 4 (of 6)

Artist writer filmmaker

Lis Rhodes, a dialogue with Nina Danino (2020)

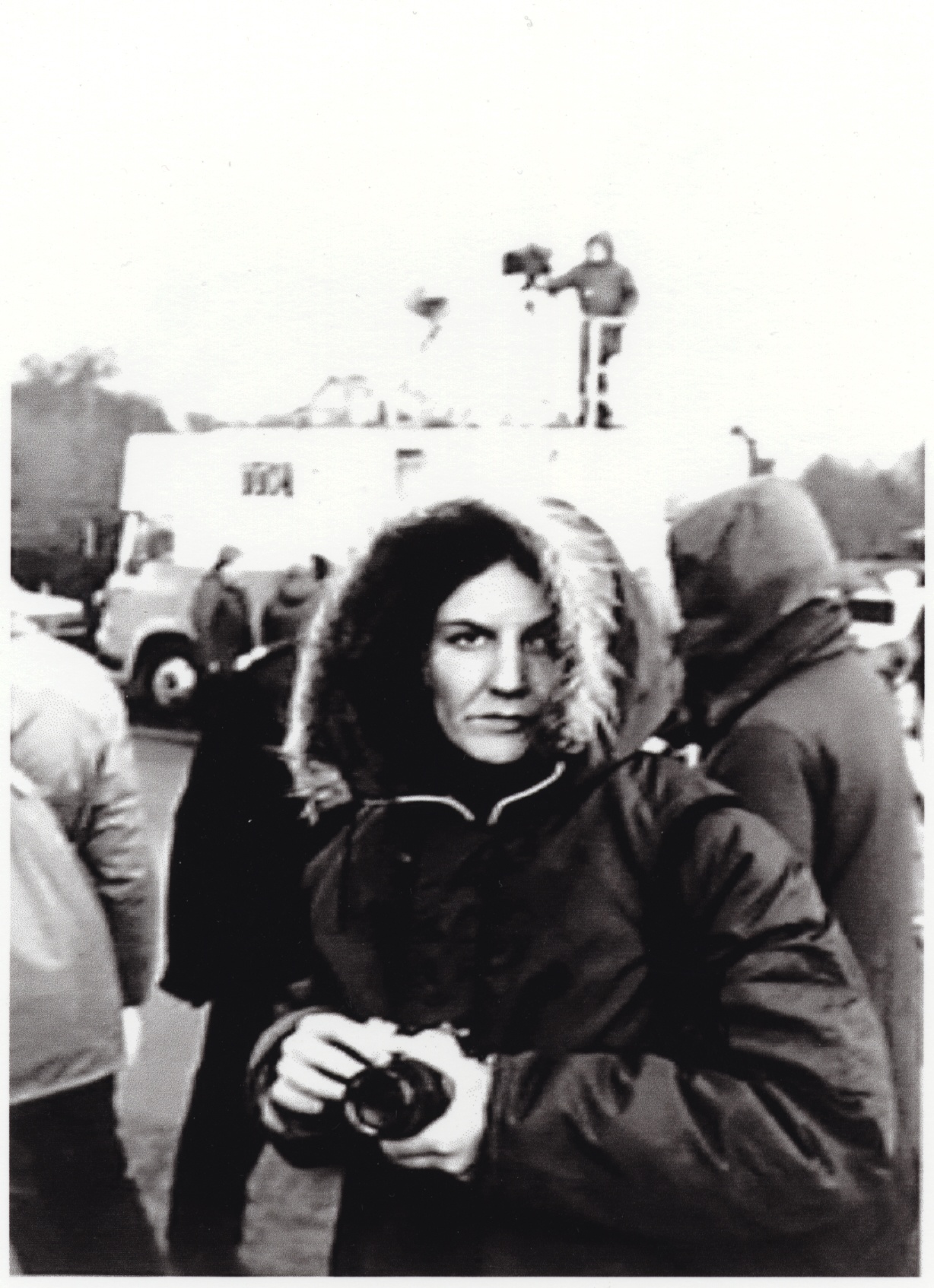

Still showing Lis Rhodes on Greenham Common (around 1982).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist.

_______________

This

conversation is one of a series of six discussions undertaken by the filmmaker

Nina Danino in 2020. They were revisited and edited in 2024 for publication

online by LUX, London. The dialogue was created through an extensive email

exchange between Nina Danino and Lis Rhodes in 2020, which they then edited

carefully, lightly checked in 2023 and proofed for publication in 2025.

________________

In this written dialogue, Lis Rhodes offers her rhythmic poetry as

a way of answering Nina Danino’s questions, which were direct and intense. This

has to do with the written nature of their exchange. Originally, Nina Danino

sent questions that were intended to act a guide for a later spoken exchange,

but Lis Rhodes replied in writing, with meticulous thought and the utmost

focus. This focus is the very aspect of the work Light Reading (1978) that fascinated Nina Danino, as to her the

film seemed to inscribe a homing into something, a seeing of something through

the camera, a framing of it as part of a long process of writing, making and

thinking. As the voiceover in Light

Reading says, “images before thought, words prescribing images – images

prescribing sounds.”

Nina Danino was particularly fascinated about Lis Rhodes’ approach to her own self-image, seen in the blurred and occasional images of her black-and-white 16mm self in the film (which also at times show, though it is not readily apparent, a male figure). Even though, as this dialogue reveals, this self-image was not her intention, these aspects of the film have not been discussed much to date. To Nina Danino,

this process of inscription seemed integral to the iconic film Light Reading and her work as a woman

artist, but the framework for this inscription outlined by Lis Rhodes is very

different to that of Nina Danino’s – connected as it is, particularly in Lis

Rhodes’ later work, to the collective and subjective lenses through which

violence is experienced by women.

The responses in the exchange that follows attest to a critical attention that is also testimony to the theme of the ‘intense subject’ in experimental film – a core theme within Nina Danino’s artistic practice and this wider interview collection.[1]

________________

This conversation is one of a series of six discussions undertaken

by the filmmaker Nina Danino in 2020. They were revisited and edited in

2024/2025 when they were published online.

Please note that the opinions and information published here are

those of the speakers/authors and not of LUX or the wider research team and

institutions involved with their funding, transcription and publication.

Published online by LUX, London (2025)

Editing and research: Claire M. Holdsworth (2020/2025)

________________

Conversation

Written correspondence (emails), April – May 2020 (edited January 2025)

_____

Nina Danino:

The discussion will touch on

how aspects of some experimental film languages can represent – a ‘speaking

from the interior’ and a female/feminist/feminine point of view through key

concepts which are; self-inscription (process), materiality (practice), enunciation

(language).

There is already an archive

on your work, as an artist who writes as an artist/writer and the connection

between writing as practice to filmmaking. Your writing for your films,

catalogue, panel discussions, interviews were published in Telling Invents Told last year.[2] I also refer also to the interview you did with Jenny Lund for Feminisms: Women artists and the moving

image, which is very comprehensive.[3] So this conversation is not to add to this body of work or to interpretations

of the films but to locate concepts of self-inscription (process), materiality

(practice), enunciation (language) in the discourse of particular forms of

experimental film, through some moments or passages and or even frames, always

understanding that this is also an interpretive activity as a way of

approaching this.

Your body of work is diverse

and goes back to the seventies, but I would like to focus on the experimental

narrative films Light Reading (1978)

and Pictures on Pink Paper (1982)

which communicate a personal expressive intensity and are intended for linear

viewing. Perhaps that way that we can find inscription in the work, perhaps it

only exists in narrative forms as moments in given works. You suggested we also

discuss the films Journal of Disbelief

(2000–16) and Ambiguous Journeys (2019).

We will also touch on your experimental film context through the 1980s and

1990s to now.

Lis Rhodes:

In the

introduction you refer to a speaking from the interior – this is a concept that

I find difficult to understand. The binary forms that words are made to take

within the structures of language force absolute divisions in meaning. Implied

in speaking of an interior is the existence of an exterior. The implications of

the two concepts are more complex, in other words they suggest the subjective

and objective.

Surely speaking from the interior and a female/feminist/feminine point of view confirms misogyny in the bias of positioning women as ‘subjective’, driven by the ‘personal’ and ‘intuitive’ – and the misogynist holding the ‘objective’ to itself – defined as ‘(a person or their judgement) not influenced by personal feelings or opinions in considering and representing facts. “Historians try to be objective and impartial.”’[4] My essay, ‘Whose History?’ questions the absence of the subjective in the definition of objectivity.[5]

Equally the word feminine

gives many women pause for thought. There is a connection between the

expression of our understanding of what is seen – in the practice of

representation – and how much that understanding has already been learnt

through previous expression. The binary separation of definition of meaning is

misleading. In reality meaning moves.

Nina Danino:

My contention is that subjectively inscribed experimental film as a language, comes out of a drive, a need, for expressivity but also the rigour of structural, formal and theoretical concerns. An essay I wrote on ‘The Intense Subject’ attempted to locate this as a place of working which was/is unique or historically specific.[6]

Lis Rhodes:

I see your need for ‘expressivity’ but surely the problem is the

artificial fissure between expressivity and the ‘rigour of structural, formal

and theoretical concerns’, which is deeply embedded in a culture of opposites.

Unfortunately this is expressed through the ideology of competition – where

most are going to lose out.

a hyphen splits the world

competition an ethic

and gambling an economy[7]

This

reveals the inequity of a prevailing ethic – in how structures of language and

economics are reflected in each other and determine lived conditions.

Nina Danino:

Naturally I am approaching

artists whose films, as do mine, I feel foreground the subject/ive through the

trope of biography or autobiography and tropes of authorship through text or

voice over saying ‘I’ or ‘she’. I feel that yours perform this inscriptive

register too. Can we explore how the notion of authorship or consciousness is

performed and constructed in these films?

Lis Rhodes:

I don’t think the question

of authorship is particularly important in the work that I try to do. The

sources of the ideas are too diverse – to consider them mine. I make work

through various means - many are drawn to mind from different times – ideas may

find links – be reordered. ‘She’ in the collective sense is the carrier of

sense, the subject of the sentence. If there is an element of autobiography the

ageing of my voice is there. It is in the pitch of my voice between Light Reading and Ambiguous Journeys, a certain measure (from the note of D mezzo

soprano to the B of the alto). That makes sense of nonsense.

Nina Danino:

The soundtrack of Light Reading is spoken in the tone of a

literary reading, did this form influence your writing?

Lis Rhodes:

I’m not sure that I have

ever been to a literary reading. If Light

Reading is spoken in the tone of a literary reading it is simply that my

voice was the cheapest solution. The film had no budget, and I had no money.

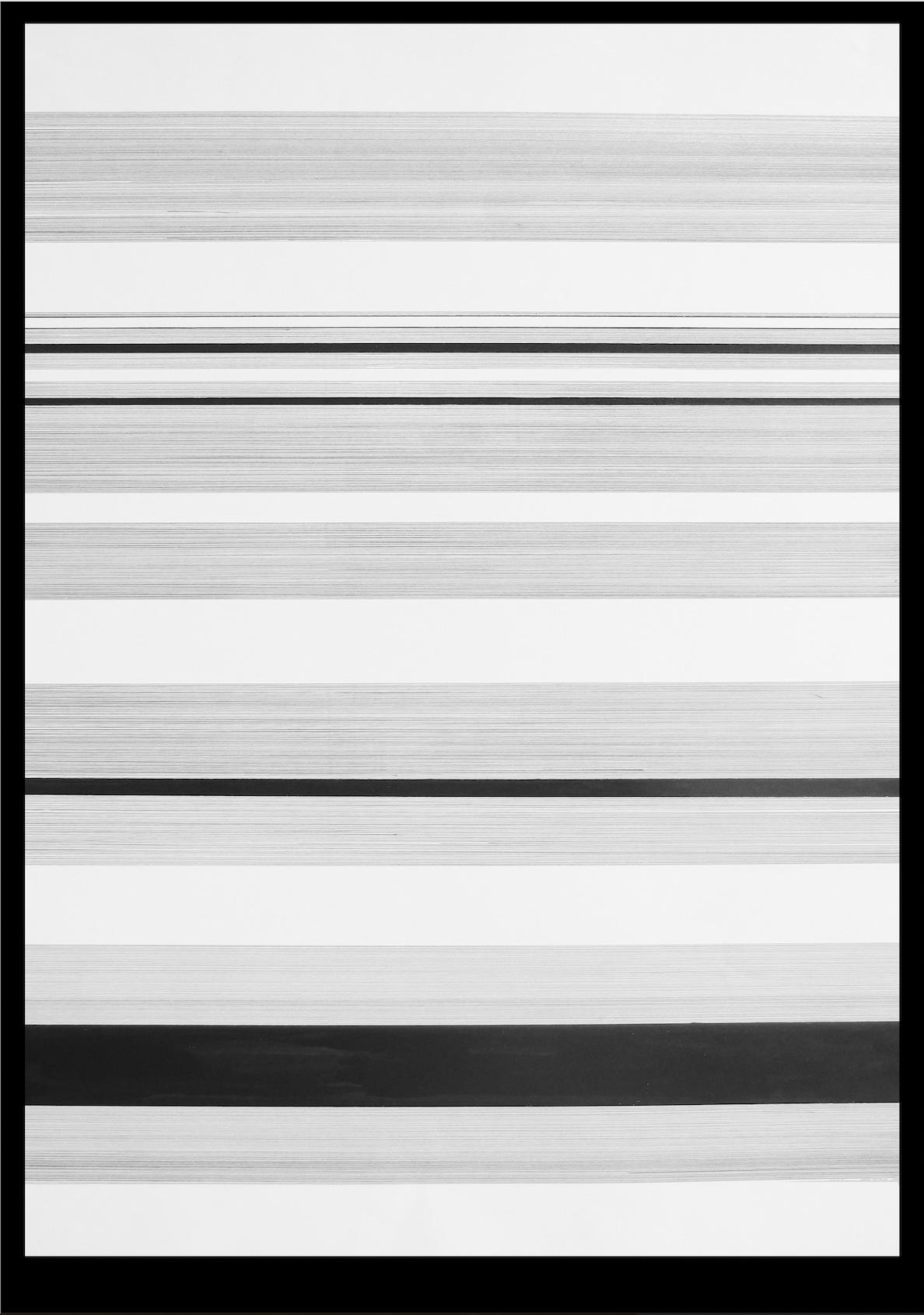

1978.jpg)

Still from Lis Rhodes, Light

Reading (1978).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

You worked in Compendium

Bookshop. Did this set a context – the scene if you like, for the inscription

of writing in your films and practice?

The London Film-makers’

Co-operative [LFMC] moved to Camden in the mid-1970s. Compendium was a hub for

writer/artists, readings/performances. Artist filmmakers performed there,

feminist writing and magazines such as Spare

Rib were sold there. There was the Only

Women Press in relation to the culture of writing – this was the context

that you connected to. It had connections to the art world – all the latest

theory books. I bought Peter Gidal’s Structural

Film Anthology (1976), Juliet Mitchell and Jacqueline Rose’s Feminine Sexuality: Jacques Lacan and the

École Freudian (1985) from there.[8] It was a centre for both ‘political radicalism and literary avant-gardist

writing’ in the 1970s, are these threads that you have wanted to keep running

through your work?

Was it poetry that influenced you at this stage? Gertrude Stein is referenced in the films and quoted as an influence on your own writing.[9]

Lis Rhodes:

I don’t think that working at Compendium was particularly

influential. Images out of the written had always been there from reading.

There is so much to say it brings relief to see sense in brevity. Maybe that is

the premise for poetry. Poetry moves between image and the notation of sound.

Working at Compendium was useful in that between the poetry – and then the

feminist section – I was working and reading the work I was doing. Something

that was rare before.

Nina Danino:

When did you begin to think of writing as part of your film practice?

Lis Rhodes:

Amanuensis (1973) was literally a

visually written film as the title indicates, ‘one who takes dictation or

copies manuscripts.’[10]

The images were printed from already used typewriter tape. The original text

was probably dictated to a secretary – almost certainly a woman. The spoken

translated into the visual. The meaning conveyed, unreadable. Later I used some

of the visual footage in Light Reading.

Nina Danino:

Was it to do with the voice in relation to writing?

Lis Rhodes:

Yes, but not my voice. The typist translated the sound of the voice, in the fragmentation of the words recorded in the silence of the visual on the typewriter tape – ‘she refused to think of the use to which that which was done would be put’.[11]

Nina Danino:

How did you decide to speak your writing? Did you draw on

performance of the poetry readings that might have been part of this milieu?

Lis Rhodes:

To read in reverse the silence of Amanuensis necessitated the decision to speak in Light Reading and that became integral to the film itself. The opening sequence is without image, just my voice reading aloud:

she will not be placed in

darkness

she will be present in

darkness

only to be apparent

to appear without image

to be heard unseen.

This is reiterated at the

end of the film:

she refused to be framed

she raised her hand

stopped the action

she began to read

she began to re-read aloud

Nina Danino:

In Dresden Dynamo

(1971-72) and Light Music (1975–77)

sound is the image and vice versa. What made you move away from this modernist

interest in concrete sound and decide to read the writing aloud in Light Reading which is read by one voice

alone?

Lis Rhodes:

I haven’t moved away from my interest in sound or its relation to

image. Dresden Dynamo was made to

counter the illusion that the soundtrack to a film has necessarily any

relationship with the visual. At the time I had no movie camera or audio

recording equipment. I made the film by hand with the intention that the sound

would be the image - the image the sound - one symbolic order read as another.

In a sense Amanuensis was similar in

that I thought the images on the optical track might have sounded. Actually,

the near silence became the silence of the written - printed from the used

typewriter tape - extracts of which were used in Light Reading. Between Amanuensis

and Light Reading, Light Music was made to counter the

apparent absence of women composers. Later, I composed soundtracks from

synthesiser notes, piano wires 5 metres long, with and without voice.

Image of drawing on paper. The drawing was then filmed on a

rostrum and became the score (printed onto the optical track) for Lis Rhodes, Light Music (1975).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist.

Installation shot (Tate Modern) of Lis Rhodes, Light Music (1975).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

The voice brings with it the subject’s whole body and presence.

How do you feel that the voice related to the body? It isn’t just vocalisations from the

experimental music scene of the 1970s, like Cathy Berberian and Meredith Monk

or Dagmar Kraus, who performs vocals in Pictures on Pink Paper. In Light Reading

the voice is saying, trying, to communicate something in and through language.

Where did you get the idea of speaking in the film?

Lis Rhodes:

The opening sequence of Light

Reading has no image. It is the voice that is present. If there was a

certain reason for using my voice, it was to question the use of English

language, its grammatical structure and binary divisions. That these questions

had been and have been raised by many women - makes explicit the shared nature

of thought. This struggle with the problems of language defining experience

runs through much of my work, realities are denied, expression suppressed.

'A word is dead

When it is said,

Some say.

I say it just

Begins to live

That day'.[12]

Did you weigh every word?

Each one

One by one?

Weighed - weighed one

against another

But if there's no comparison...

No memory

There will be...

No dissent [13]

The idea of speaking in film

was implicitly there in the silence of Amanuensis.

Nina Danino:

How does Light Reading enunciate an authorial

consciousness which could be called inscription?

Lis Rhodes:

The consciousness in Light Reading is hers, she is the carrier of sense:

in her own voice she cried

the end cannot be confused

with the end that ended

somewhere

but not here not here at the beginning.

Nina Danino:

Certain experimental forms in film might be read through a notion of authorial consciousness. Anneke Smelik in And the Mirror Cracked[14] talks about the ‘female subject’[15] as a multi-layered, embodied inclusivity, feminist consciousness is a process that structures relations between direction, film text and spectator, a film form which encompasses strategies and rhetoric. I found her use of literary theory transposed to film convincing because it points to an understanding of the totality of film as a discourse.[16]

Lis Rhodes:

To begin I haven’t read Anneke Smelik’s book And the Mirror Cracked. I’ve never worked within the parameters of

direction, film text and spectator. I think that there may be an underlying

problem in constructing a definition of the ‘female subject’. This is

compounded in ‘feminist consciousness’ – of which there are so many we shall

never know. I think perhaps we should be wary of defining even [as you said]

‘multi-layered, embodied inclusivity, feminist consciousness’ since lived lives

– in their particular context – are infinitely varied. I suppose that the

immediate question is, who is excluded from this multi-layered embodied

inclusivity? I think that I am addressing the problems that women face, not

attempting to define a female subject. Wouldn’t that be the imposition of yet

another limitation not a liberation? Definitions raise problems in their

fictional finality. Everything moves, except misogyny itself – why, oh, why?

Nina Danino:

In Pictures on Pink Paper we hear several women’s voices talking aloud

but there is one voice that asks the questions – a sort of consciousness over

the other two (three?) which lack the same reflective interiority. Is it when

these elements cohere that we reach the discourse of the authored consciousness

of the female subject?

Lis Rhodes:

I did many recordings for Pictures

on Pink Paper (1982). There were five voices in the final version including

Dagmar Krause and myself. The suggestion is that when these elements cohere,

there is a consciousness of the female subject. This implies a certain stasis

in discourse and objectification of their voices. The last words sung by Dagmar

Krause are –

does nature produce

the nature in us

or is it their nature

that’s natural – not us

is it natural in nature

to subjugate us

or is it naturally

nature to them – I mean men

to think of a nature

especially for us

a feminine nature

designed by them

but naturally – quite

unnatural to us[17]

These are really the questions that came to be the work that’s

heard and seen. I again stress there can be no singular ‘female subject’. There

are infinite female subjects. Each voice remains particular. Between the

particular there are certain shared concerns.

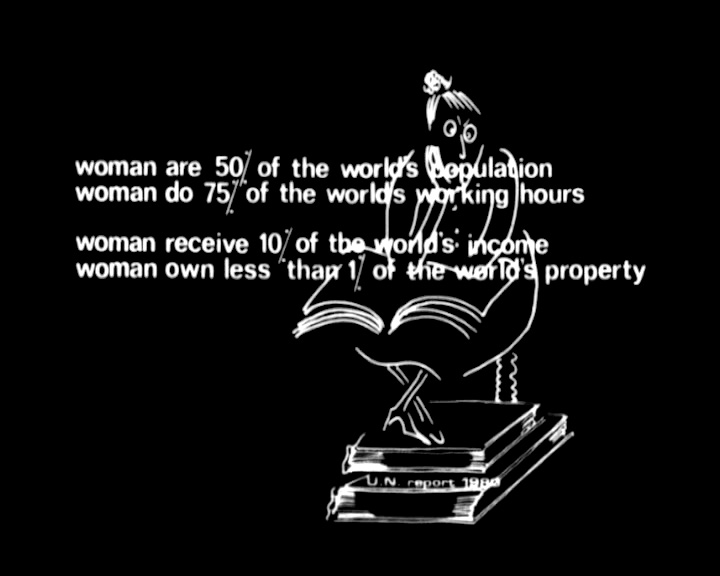

Still showing drawing by Lis Rhodes alongside statistics from ‘UN

Report c.1980’ in Lis Rhodes, Pictures on Pink

Paper (1982).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Yet this consciousness

suggests introspection it is in flux and in Light

Reading it is a constant state of self-questioning or self-interrogative

speaking in a rhetoric of anxiety and indecision, ‘shall I?’ spoken in the

cadence of poetry, such as rhythmic address.

Lis Rhodes:

Light Reading is, in the sense of a

constant state of questioning, a continuum of critique of the structures of

language, which attempt to define so much of the world as it was and still is.

And still women are having to argue and explain the obvious.

was she working back to

front

front to back

images before thought

words prescribing images –

images prescribing sounds

which was in front of why

was it just the orientation

of her look

the position of her

perception

the back of the front

or the front of the

back

she listened

she looked at the soundings

of the image

[18]

[…]

Nina Danino:

I think struggle is an

important part of the consciousness of the subject as a register in/of these

films. Your films often deal with the discourse of social strife which to me

can also be understood as conveying a subjective experience. This struggle then

extends to the form of experimental film practice itself – a form which is not

easy, it doesn’t come easily, and it shouldn’t. It is a struggle to make a new

form for oneself between and the process of making film in the search for

(self-representation). Does this strike a chord with you?

Lis Rhodes:

I’m hearing several chords in your question. Understanding is

complicated, so much is hidden suppressed – refuted and erased. Dangerous for

some, reflected in the number of writers who are or have been in imprisoned. I

see the ‘struggle’ not so much between making a new form for oneself and the

search for self-representation, but rather taking apart the abstract structures

– law, education and economics – that determine how division enforces

oppression. This in itself necessitates an undoing of established forms of

language. Telling this as it is – be careful, truth is a commodity, and it

tends to cost.

Nina Danino:

How do you build in

discourse of a female subject in your films? Is it the use of pronouns?

Lis Rhodes:

she laid the words with care

among the dripping plates

the issues are defined

what is spoken – that is

seen

in black or white – as left

or right

either ... or

two sides to every question

[19]

A pronoun cannot hold the diversity and complexity of gender. It

may work as an indicator in certain contexts. There are many ways to move, in

questioning the two sides of the answers given – the underlying patterns of

control need constantly undoing. I question – the binary opposite of this to

that. Their movement together is the moment of concern and hope. It is

obviously necessary – so many women from all over the world are doing just

this.

Nina Danino:

You write ‘saying what you mean within the confines of syntax is

like squeezing sense from the imaginary.’ In this space of what is squeezed out

is the subject – in abstract structural film, the woman is squeezed out, only

to appear as enigma – the mastery of the apparatus in structural film is itself

the means to an end. How did you cope with this ‘becoming enigma’, did it lead

to the necessity to project yourself through enigmatic concealment in order to

carry out your work?

Lis Rhodes:

As I understand ‘abstract structural film’ it is associated with

the ideas of the structural linguistics of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de

Saussure, the anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss, and later by writers such as

Roland Barthes, Louis Althusser, and Jacques Lacan. If this is the case – that

she is squeezed out of the concept of abstract film it is similar to her

exclusion from musical composition, theoretical mathematics, philosophy and the

underlying structures of language. This is precisely where she was, and needs

to be, but her contribution has been erased. These are the systems that define

the conditions that determine living – and surely it is here that change is

long overdue. Is this ‘enigmatic’? This concealment and erasure of the work

done by many women is still suffered today. Just as domestic work and the low

pay of care workers indicates the disregard of the importance of the work they

do.

Nina Danino:

You show the close up of a face in a compact mirror in Light Reading – it is an image which is

in soft focus. Was this reflection in the mirror a part of the necessary

condition of being and presenting yourself as a woman and the woman artist?

That is, the artist’s confrontation with image and self-image?

Lis Rhodes:

The mirror image is where she was meant to be – and so I had a

look at it myself. The questions that run through Light Reading are looking at the abstract means of oppression that

underly the more overt problems that women are still facing within the varying

extremes of patriarchy.

she watched herself being

looked at

she looked at herself being

watched

but she could not perceive

herself

as the subject of the

sentence

as it was written

as it was read

the context defined her as

the object of the explanation

[20]

Still from Lis Rhodes, Light

Reading (1978).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Hair can be the synecdoche and fetish of self-presentation for

woman. Barbara Meter’s film Traces

(1990), which is removed from

circulation, stayed in my memory through the slowed

down sequences where she is walking and is crowned by wild hair. Your red hair

as a young woman makes me think of a Pre-Raphaelite maiden. Not Ophelia who is

horizontal and thus passive, this figure is standing. Is this photograph the

signifier for the filmmaker and the self?

Lis Rhodes:

The analogies you are suggesting are male concepts. You are quite

right that hair is culturally determined and can be used as a method of torture

and repression. Just this morning I have been looking at a photograph of the

mayor of Vinto in Bolivia in a newspaper article which describes how, on 7

November 2019:

an opposition mob stormed

the municipal headquarters and dragged the mayor Patricia Arce, into the street

before setting the building ablaze.

Morales said in a tweet on

Thursday that Arce – a member of his ruling Movement for Socialism (MAS) party

– had been “cruelly abducted for expressing and defending her ideals and the

principles of the poorest.”

Television images showed her

on the ground, her hair cut, and covered in red paint. She was dragged and

forced to walk barefoot through the town by the mob before being rescued by

police on motorcycles.

Morales’ party demanded the

police bring the perpetrators to justice.

Arce’s office told local

media on Thursday the mayor “is recovering” from her ordeal.

[21]

In the words of my film Riff

(2004):

women accused of

collaborating

had their heads shaved

the deportees who returned

were mistaken for

collaborators

their heads too had been

shaved

being identified is both

ritual and illusion

[22]

Women’s hair is uncovered as a sign of ‘freedom’ and covered as

‘control’ – both unnecessary symbols.

Nina Danino:

In the process of self-portrayal in Light Reading does the subject and object come into conflict in

that compact mirror? Did you see this film as a catalyst or a drama of/for

‘selving’?

Lis Rhodes:

No, I don’t see the images in the compact mirror in Light Reading as ‘selving’. In the film the compact mirror reflects both genders in a frame usually intended to reflect the female only. Light Reading is a reading of violence towards women – whether physically or in the abstraction of language. Felicity Sparrow wrote that the ‘film begins in darkness as a woman’s voice is heard over a black screen. “She” is spoken of as multiple subject – third person singular and plural.’ [23]

Light Reading ends with no single solution. But there is a beginning. Of that

she is positive. She will not be looked at but listened to:

“she begins to re-read – aloud”

[24]

Nina Danino:

Thinking about visibility and woman as author, do you want to be a

veiled figure both in your work and as a persona? Was film authorship part of

an impulse to evade exposure or to come into the field of vision? Is the

avoidance of clear figuration part of the impulse to resist

self-representation?

Lis Rhodes:

I am not resisting self-representation. Light Reading is a critique of how women are imaged – without

voice:

she watched herself being

looked at

[25]

[…]

she refused to be framed

[26]

The

structures of language and the violence implied both mentally and physically

towards women are at issue here.

Still from Lis Rhodes, Light

Reading (1978).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Anneke Smelik says that the speaking subject in discourse is

present, whilst in story they are masked. The subject of enunciation is the

cinematic apparatus as a whole – camera movement, montage, point-of-view,

composition, soundtrack and so forth. The discourse of subjectivity is both

questioned and presented, enunciated in these experimental films through the

camera or sound and editing and the development of experimental film language

to create new forms of representations as authors. We are looking at visual

language in film as part of authorial consciousness – could we look at your

visual language?

Lis Rhodes:

Anneke Smelik makes an interesting comment, but at what point does

a discourse become a story – a story a discourse? The news reader uses the

phrase ‘news story’. The speaking voice is reading the editor’s script – both

are masked – in the representation of the facts. Or are these facts stories?

Equally but differently, the voice in discourse may tell a story whether true

or not – the mask is shared. Do we rely on the filmic equipment to tell us a

truth of authorial representation? If I have a visual language, it is in the

writing I write and the sounds I compose – the images I paint and the paintings

I image.

Nina Danino:

You made expanded works between 1971 and 1976 in an

interdisciplinary context of the avant-garde practices of performance,

experiments in music, structural film, mainly in London and New York. You

resist being read within one form of production instead incorporating a range

of interdisciplinary practices which span across installations, sound and

linear film and you have said that you do not wish your work to be sectioned

off into different compartments.

Lis Rhodes:

I think that most of the expanded film works that I was involved

with were made between 1973 to 1976. The initial thinking was to undo the

established cinematic structure of film to audience. At the ICA [Institute of

Contemporary Arts, London], Ian Kerr and I did a nine-hour performance, Bwlhaictke (1976) with two 100-foot

loops of film where the soundtrack was made while the audience came and went.

The sound gradually increased in intensity from near silence at the beginning

and again at the end. At the Acme Gallery [London] we performed the action of

editing and re-editing in a series of variations on a short piece of music

composed by Cornelius Cardew for the performance CUT A X (1976). It was a live performance creating a series of

variations in sound. In a sense there was no film – there is no film. It all

happened once.

Nina Danino:

You studied at North East London Polytechnic, was that in

Painting? What led you to take up filmmaking as a practice?

Lis Rhodes:

No – it was Communication Design. It was very simple – I wanted to

understand sound in relation to image. In word and image – voice and depiction,

sentence and scene – there is construction of an apparent veracity – a

transparent relationship between what is seen and what is said, which I didn’t

always see and didn’t necessarily believe.

Nina Danino:

In identifying the means of

production as a way of also trying to locate the operation of inscription is

perhaps obvious, but I feel it is the one place where we must look because it

is different from artists’ moving image where content is a given. Perhaps we

need to do this by going into Light

Reading. Would you draw out the relationship between the means of

production and the purpose for which you were using it?

Lis Rhodes:

With great difficulty – I don’t seem to work quite as your

question suggests. I usually find myself working between the sound and drawing

– image and writing. Some images in Light

Reading, as I have already mentioned, emerged from Amanuensis (1973) and then from another short piece of work made in

1975. So the images, conception and writing came together gradually, rather

than in a consideration of ‘production’ and ‘purpose’. This is why experimental

can be a useful word sometimes. The search is to disturb accepted meanings that

permit oppression and exploitation – necessitating re-thinking systems of

production. Hence the significance in Dresden

Dynamo of negating any illusion between what is seen and what is heard. A

noisy moment in the search for precision in the relationship between the heard

and the seen.

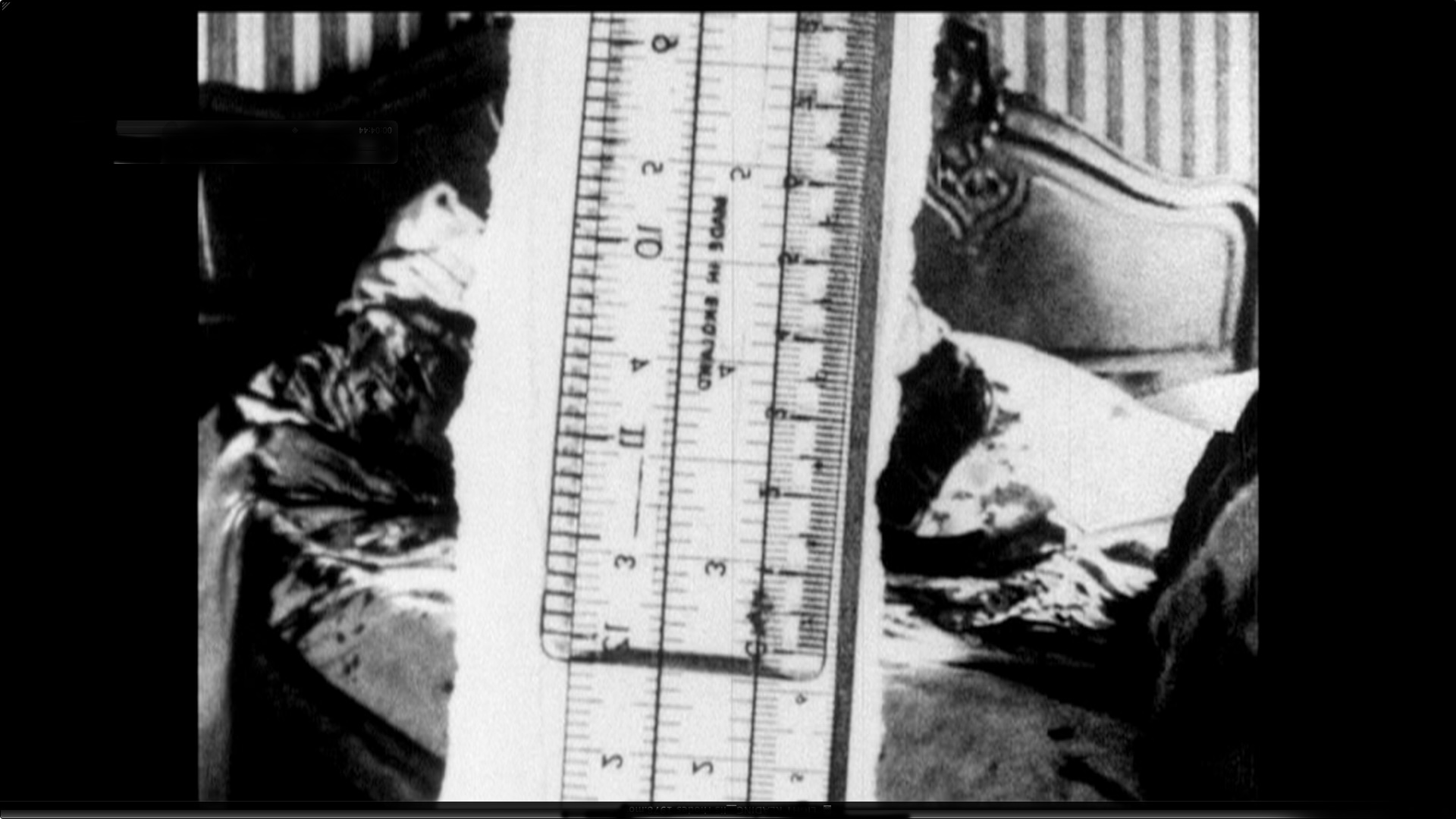

Nina Danino:

Would you talk about the rostrum camera in relation to the visual

language of Light Reading? In Light Reading we see the materials:

rulers, photographs, torn newspaper article, being arranged and re-arranged.

Previously you had made films without film, was this the first time you were

using this piece of equipment?

Lis Rhodes:

I used a rostrum camera in the making of Light Music. The composition of certain sounds is determined by the

distance between the lines of the original drawings. Read by the optical head

on a 16mm projector the distance between the lines changes the pitch of the

sound. The speed of the zoom changes pitch and tempo of the sounds. So, in Light Reading there was already

experience in using the camera. The problem was getting access – that certainly

took time.

Nina Danino:

I’d like to ask about your

process of work. Did you make Light

Reading at the Royal College of Art [RCA]? I recall using the rostrum at

the RCA which I used to make my first film which is not in circulation It was a

large dark room professionally set up.

The rostrum was commercially

developed for animation; much experimental film can be thought of as animation.

You could exert close levels of control, whereas working as a director with a

crew was perhaps a role less inaccessible to women. Did the access to the means

of production as a woman at the time have a bearing?

Still from Lis Rhodes, Light

Reading (1978).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Lis Rhodes:

I don’t get the impression that working as a director with a crew was remotely possible in the 1970s. Certainly for a woman filmmaker with no budget, I was very aware of the constraints on women filmmakers when I joined the union, the ACTT [Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians] in the late 1970s as a sound recordist.[27] There were practically no women camera operators or sound recordists. I also wonder if such a hierarchical mode of work would have undone the premise and way I was working on film.

Nina Danino:

Was it just available – because improvisation also plays a role –

not everything has to be controlled to the frame does it? Did you work it out

as you made the film, or did you have a plan? How did the rostrum open the

possibility of exploring film in different way to you as a woman filmmaker?

Lis Rhodes:

No – Light Reading wasn’t made at the Royal College of Art. I can’t

actually remember where I made it. It might have been Croydon Art College where

I was teaching.

Still from Lis Rhodes, Light Reading (1978).

Copyright Lis Rhodes.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Lis Rhodes:

Light Reading was made over a number of

years – much of the visual material I had printed by 1973, the writing written

from time to time, the images gathered similarly. There was no budget. The work

I do is focussed on the abstract systems that control and measure, so I have

tended to avoid representing the symptomatic as natural. In that sense, a

rostrum camera was both logical and useful.

Nina Danino:

Inscriptive practice could be an attempt to give meaning through

process with reference to structural/materialist film practice which provides a

rigour through a notion of pushing the machine to its ideological limit, albeit

that materialist film wanted to do the opposite, to empty meaning.

Lis Rhodes:

It’s difficult to empty

anything of meaning. Nothing means so much. A line of words across the borders

of a sentence – the image is drawn away. To capture meaning without control –

is difficult to do. Whether that is the grammar of the English language – or

the legal implications of law – there is no separation in the means and power

to capture.

Nina Danino:

As a woman, did the mechanical means of production become a machine for looking for something and meaning giving? Literally looking through the lens and the act of looking is intense. What were you looking for in your process could you look through the lens of the rostrum camera?

Lis Rhodes:

Well, if I remember correctly, I did look through the lens. This

can need a short ladder. But I used several different rostrum cameras –

sometimes at night when not in use by technical staff. With Light Reading the action was more

performative – often literally movements by hand.

Nina Danino:

Can you comment on what kind of looking you were doing – what was

it enabling you to see?

Lis Rhodes:

[…] some things are very

disturbing

and so they are

that is how they are

intended to be

[28]

The succinct attributes of

lines drawn and drawn in words can be very fast in undoing the order of things

– as they are assumed and imposed to be – which is useful when finance is short

and time curtailed.

Nina Danino:

Did your engagement with this mechanism lead to seeing something

you hadn’t seen before or to discover or to do something that couldn’t be done

in the forms you’d been using? Of course, it must give you the power of

control?

Lis Rhodes:

No, not seen before – but yes, it definitely led to something I

hadn’t heard before. This was the relationship between a particular distance,

between lines drawn on a piece of paper that would create a sound that was the

approximate equivalent of a middle C [musical note].

Nina Danino:

How have you transferred this memory in your practice, from

mechanical to digital films today? In your most recent film, Ambiguous Journeys (2018) there is a

repeated series of digital horizontal and vertical pans which frame the text a

bit like Peter Greenaway’s film Vertical

Features Remake (1978). I wrote down in my notes ‘The metaphors of words

and Journeys. Rostrum pull ins and pans combined with stretches’.

Lis Rhodes:

There is no rostrum work in Ambiguous

Journeys. The movement in the images is digital. Usually, I work with the

sound and image together – not one and then the other. But with Ambiguous Journeys I composed the

soundtrack first, recording my voice and using single notes played on a

synthesiser, collected over time, to construct the sound to the voice. It was

in the composing of these digital notes that I stretched notes individually –

changing the pitch and duration – that led to a similar response with some

images: the sound shifting the image, the image defining the written. The text

is open to be read, heard, or both.

Nina Danino:

Can you talk about the act of framing and reframing, as a

repertoire in your visual practice?

Lis Rhodes:

In Journal of Disbelief

(2000–2016), which deals with various aspects of law, there is an image of a

sign – framed and reframed behind barbed wire – of the notice naming the prison

Camp Delta JFT Guantanamo in Cuba. This carries the inscription ‘HONOR BOUND TO

DEFEND FREEDOM’. Written on the images in Journal

of Disbelief is the text:

[image]

with a shift of perspective

[image]

similar actions are

differently judged

when viewed

from a different point of

view

[29]

How this critique will be read depends on who is reading and why.

The framing and reframing call judgement into question.

Nina Danino:

You are against metaphor, so framing is a form of emphasis and

visual control through which you direct the viewer’s eyesight and ideological

attention isn’t’ it?

Lis Rhodes:

Yes. The evidence is there in representation. The frames are

framed to initiate a questioning of the meanings implied.

Nina Danino:

Can you comment on framing

from the perspective of gender?

Lis Rhodes:

In Light Reading the

text takes a direct swipe at gender inequality – through the ideological

structures in language, to the question of who defines the frame in which she

is to appear within.

[…] her thoughts framed

her image outside the frame

re-framed – by whom

in whose frame

[30]

[…] she was seen as object

she saw as subject

but what she saw as subject

was modified

by how she was seen as

object

she objected

[31]

Nina Danino:

My third question is about the soundtrack. Did you train as a

sound recordist in the 1970s? Many experimental filmmakers moved across sectors

– documentaries for television too. We weren’t isolated.

Lis Rhodes:

I didn’t train as a sound

recordist or work for the BBC – I simply joined ACTT. My work has been shown on

Channel 4 and the BBC and the Hang on a

Minute series was funded through the workshop agreement with Channel 4.

Nina Danino:

Returning to the voice – what were you trying-out in Pictures on Pink Paper? You add several

women’s voices and sound effects. When

I made First Memory (1980) I had not seen Light Reading. I made my recordings

in the sound studio at Environmental Media at the Royal College of Art in total

isolation and my use of the voice came from my interest in writing and

narrative literature.

Lis Rhodes:

Perhaps Pictures on Pink

Paper is a philosophical narrative – without beginning or end. A play

between the women’s voices – who speak the words I wrote:

to try to make real

what is unreal

is to mistake the nature of

things

but if the nature of things

is a deliberate mistake

and really not so real

then it’s quite essential

to make real what is ideal

it’s all a question of

who makes real – whose

ideals

whose values are valued <

as the nature of things

i think ... she said

[32]

The catastrophic acceptance of established meanings permits the

use of phrases that are slanted to justify power – as a natural state of being.

Nina Danino:

Many structural films are

silent or mute, thus revealing its own condition of material and thus also

being anti-illusionistic. The sound to Dresden

Dynamo (1971/2), a structural film with a scattergun/staccato noise, is

produced through the application of Letraset alphabet letters on the physical

film itself. In Light Reading in 1978

you decided to use speech in voice over, what made you do this? Did the

feminist context enable this move?

Lis Rhodes:

In Dresden Dynamo the sound is the image.

The sound is not intermittent. It is exactly as the optical head reads the

image. The image laps onto the optical track. This determines the level of the

sounds – there is no actual silence. What is heard – is seen. There is no space

for manipulation as there usually is in the editing of sound to image.

As I said earlier, Amanuensis was made to hear how the used

typewriter tape would sound – would the fractured words be readable. In Light Reading if words were to appear in

the film it would be in terms of voice not image. Women’s resistance had a long

history before Light Reading was made

– philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in A

Vindication of the Rights of Woman in

1792. I’m sure that the voices I was hearing and the books that I was

reading at the time were influential.

Nina Danino:

Ambiguous Journeysand Journal of Disbelief have an electronic sound composition adding a

strongly evocative layer. Can you comment on your decision to use music? We are

free to create accessible and viewer orientated reception for films at a

different time and for a different audience – did you want to assert this too?

Lis Rhodes:

In Ambiguous Journeys I

was editing the voice track at the same time as making various short phrases of

sound, which perhaps indicates how closely the sounds affect the words. The

words are phrased to the sound seen within the image. I don’t know how a future

audience will hear this composition or read the film. At the Nottingham

Contemporary exhibition in 2019 the film was screened in the context of The

List of 36,570 documented deaths of refugees and migrants due to the

restrictive policies of ‘Fortress Europe’. The context will change.

The Journal of Disbelief is different in that it was to be a film and book at the same

time. To be seen in sound and silence – to be read in silence. So far it is

only the film that is complete. The composition of the soundtrack is far from

the image. Some of the sounds as they are come from elsewhere. I recorded them.

There were the voices I could hear and those I couldn’t hear. The sound is

episodic – as is the journal as a format.

Nina Danino:

Recently your work has received solo shows and is being

recognised. What do you take forward from that experience with regard to facing

a new public for the work?

Lis Rhodes:

I think that there is a wide recognition that inequity is now so

great – the damage being done to the planet is untenable – international law is

being broken – violence is endemic underwritten by the arms manufacturers and

traders – and governments represent finance not the people. Young people are

very aware that this must change. I’m with them.

Nina Danino:

The 16mm expanded works between 1971 and 1976 that we have just

described between Dresden Dynamo and Light Music fit in well into the museum

and gallery installation today. The formal and physical aspects of the

installations work for a museum audiences but conversely I wonder if the linear

works are too intense for a gallery viewership? I’m talking about my own films

too here and the other films that have this in common. It’s this that I am

interested in – that aspect of ‘being too intense’ what is that exactly?

Do you call your practice

today say Journal of Disbelief,

artists’ moving image, or experimental film or do you see experimental film as

a historically specific practice? Does it matter? Is it relevant?

Lis Rhodes:

I follow what you are saying. The context of screening matters.

Many films – yours included – need the quiet seating of a cinema – a reading of

film that opens and closes in a linear sequence. In the expanded work that I

was involved in the ICA Festival of

Expanded Cinema in 1976,the Tate in 2009 and 2012 the gallery provided a

space where the transitory presence of the audience – in some degree – undoes

the hierarchical structure of the cinema. I think that the concentration of the

audience can be as intense in either case – gallery or cinema – but differs

depending on the consecutive time needed to read and consider the work being

screened. The gallery space makes this more problematic as the audience is

mobile. This was brought into focus in the setting up of the exhibition Dissident Lines last year – where the

crossing of the various film soundtracks was very carefully arranged

acoustically. It allowed the various prints on the gallery walls – including

the LIST – to be read in the trace of

the film sounds.

In answer to the second part

of your question – I would say no, I am not an artist of the ‘moving image’. I

am not sure that images move – light moves and digits change; but image has no

movement. That surely is an illusion. I’m certain that work depends on context

and the sharing of ideas but not – by definition – under a certain heading.

This is – not of course – always my decision to make.

Nina Danino:

The means and materiality. I

would like to explore the concept of materiality which, in the context of your

current work is digital. The experimental filmmakers that I have talked to,

associate materiality with a direct relationship to a physical hands-on

engagement, with formal mechanisms and 16mm celluloid, but like many artists

now, you produce your work entirely on digital.

Still from Lis Rhodes,

Ambiguous Journeys (2019).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Lis Rhodes:

I began to use digital for sound editing in the mid 1990s. I found

it was more effective for the detailed work in the composing of soundtracks

than recording and cutting reels of tape. There are perhaps more problems in

the controls that are implicit in the digital software that determines the

visual. I still use early versions of imaging software which I find more

flexible and less predetermining than recent ones. But how I actually make the

original sounds can vary from the construction of piano wires in a cellar for Orifso to combining and rephrasing

digital notes in Ambiguous Journeys.

The physical presence of hands is there – in the making of sound and frequently

in the making of images – the final production is digital.

Nina Danino:

We can think of experimental film as inscribed in practices that

are mostly founded in analogue film practice through an inscribed memory or

embodiment of process. Where do we look for it post analogue – I feel that if

it exists, we have to look for it elsewhere too.

Lis Rhodes:

If we are taking the meaning of inscribe in its original meaning

[in – ‘into’ + scribere ‘write’] then it would mean that I have used

‘inscription’ in both analogue and digital work. This relates to my

understanding of the tension between the image and word – the word as image.

Are the external controls of the digital software more direct than hands-on

engagement with 16mm film? Through the software – probably – through corporate

surveillance – possibly.

Memory is obviously crucial

in all human consciousness – the loss of memory a tragedy. It cannot but be

there inscribed in all work – even artificial intelligence has its prejudices

inscribed.

Nina Danino:

I wonder if from the foundations of a hands-on practice (indeed we

see your hands under the rostrum in Light

Reading) how you approach materiality in your working process now?

Lis Rhodes:

You refer

to my hand under the rostrum camera in Light

Reading. I do not see any material connection between this image and

materiality other than the imprint on the film surface.

My fingers are working back

and forth across the keyboard at this exact moment – less interesting than the

image of the hand itself – but hands on – instructive to the apparatus.

In both the image of a hand

and the instructive use of the fingers is there a tenuous materiality? Is

playing a piano rather than a violin indicative of a loss of materiality? But

in all cases, the instruction to the apparatus is similar. I can’t see how this

varies except in the increased methods of instruction – electronically rather

the mechanical – that doesn’t negate the greater control that is lost to

software.

As an artist much of my work

has been – and still is – in the making of images before any mechanical or

electronic equipment is used – a pencil will do – or indeed a pen.

Nina Danino:

For me materiality can be thought as a way to get to deeper layers

of meaning through process. An engagement with materiality leads to a form of

intensity of engagement but what does this mean, where can one locate it?

Lis Rhodes:

The intensity of engagement is difficult to measure. What affects

one may not another. Feeling is part of thinking but I think that materiality

may be indicative of symptom – not of cause. There is a queue outside the bank

– is the bank about to go bust – or short of staff? The layers of meaning are

degrees of materiality.

Nina Danino:

Ambiguous Journeys and Journal of Disbelief are digital and it will be less obvious as to

where to look for it. Both films use a non-narrative flow of images which are

processed and highly treated, creating a textured aesthetic. Jenny Lund

describes the visuals as painterly, textured, visually rich and tactile images,

moving between sharp realism and grainy abstraction.[33]

The images are highly treated in post-production is that right? Could one think

of digital postproduction itself as an engagement with materiality?

Lis Rhodes:

Journal of Disbelief was made in short sections – digitally – some images were originally painted, others collaged – the writing integrated. There was no post-production. It is a journal. The only post-production in Ambiguous Journeys was a final sound mix with Mick Ritchie. If there is a materiality it is in the monopoly ownership of the means of production by Microsoft, Apple, Adobe etc. They also own the Cloud alongside companies like Amazon, and have all invested huge sums in creating ‘homes’ for our personal data. In a sense, materiality has been transformed into a language that few of us are really familiar with – a pre and post production monopoly. A materiality over which we have little or no control.[34]

Nina Danino:

Is there a process there, a pleasurable engagement with the

material – which includes the digital, for example a later film like Ambiguous Journeys?

Lis Rhodes:

Ambiguous Journeys is a tragedy – the deliberately-made damage done by neoliberal

economics and finance capital – the exploitation and the forced movement of

people from the devastation of war. The material making of Ambiguous Journeys was tragic too.

Still from Lis Rhodes,

Ambiguous Journeys (2018).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

We have discussed the relationship of the means of production:

technology, materiality and mastering in women’s films. How does thinking about

materiality enable you to talk about the subject and object, the her and she

that the writing always refers to. How did you feel these means communicate the

she in vision or obscured from vision? Perhaps we can touch on context of the

London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC]. My retrospective construction is that of an

LFMC as the point through which these ideas intersected.

Lis Rhodes:

We talked about this

question earlier. It is certainly present in the exploitation of women – where

vision sees in recognition. Assumptions are permitted in the systematic

appropriation of image. The focus is already framed – before the image is read.

The subject – her image is present in words – the ideology permits their

freedom. The object is forced into being without image. There is no image of

the value of her labour – that has been stolen.

she wrung her hands

round the twisted cloth

and squeezed

the drips that were

to drip down

from their freedom

to wrench their profits

from her labour

[35]

I wasn’t very involved with the LFMC after 1975 or 1976 when I was

running the cinema – and I don’t think that these ideas were being discussed

very much then.

Nina Danino:

It follows that the relationship to material and materiality was

an approach which was developed through the structure of the LFMC in its

diverse manifestations i.e., not just as a physical building or workshop

facilities, but as an ethos and position to film practice as was discussed at

the round table ‘Women of the London Filmmakers’ Co-op,’ and there are

different individual experiences of it.[36]

In the late seventies, who were your peer filmmakers in the film context around

you, who were important to you? Were there particular experimental films that

influenced you?

Lis Rhodes:

It was more the books I was reading – particularly the poets –

that probably influenced the work I was doing. Then in the early 1980s I worked

with Joanna Davis on the Hang on a Minute

series (1983–85) for Channel 4, and with Mary Pat Leece on the initial research

for the film Running Light (1996).

Annabel Nicolson’s Reel Time

performance in 1973 was a transitory moment of great significance.

Nina Danino:

My generation was in the 1980s when the LFMC was a very diverse

place in terms of the work that was shown and different camps using it. You are

associated with the 1970s modernist avant-garde of structural film which is the

first generation of experimental film in Britain, but ‘structural film’ was

diverse too, contrary to perhaps how the scholarship unifies and selects the

history. There are camps and different approaches to it even within the UK and

it also connected to music scenes and to performance in different ways as well

the literary milieus and writing contexts that we described earlier.[37]

The LFMC as an artist-run

collective succeeded in creating a culture for film/video as an art form for

artists and a medium specific practice in the context of avant-garde and

modernist experiments in performance, music and projection as described. Were there

particular artists or filmmakers at the LFMC who influenced how you developed

your thinking about your work?

In your time at the Co-op

cinema in 1975–76 what are your thoughts about your film programming there?

Lis Rhodes:

You have headed this section

on the LFMC as ‘Britain and the LFMC’ – my experience was not quite that. As

cinema co-ordinator in the mid-1970s I was screening work from Germany, France,

Italy and the USA. Sometimes with the filmmakers present sometimes not. I agree

with your remark that scholarship unifies and selects history, and tends to tie

things together categorically. To suggest it was the first generation will

exclude earlier individual artists working in film in Europe and elsewhere. I

think the uniqueness was in the presence of the London Musicians’ Collective

[who shared the same building as the Co-op] and the importance of performance

work to artist and musicians.

Nina Danino:

The LFMC was also a centre of production through the workshop. Is

there an aspect of your aesthetics which relate to the context provided by the

LFMC? Did you make films there?

Lis Rhodes:

I didn’t actually make films at the LFMC – but I did use the

[optical] printer and then Filmatic laboratories to process the prints. Access

to the printer was essential – in the printing of a sound track from split 16mm

frames for Light Music – I don’t

think even Filmatic would have attempted this.

Nina Danino:

The LFMC was also a critical and theoretical space. My connection

with this aspect of it was through Undercut

which in the 1980s played a part connecting experimental film practices,

critical/theoretical writing and artist’s writing. It published artists’

writings and on the work of peers which was different to being mediated by

curators, gallerists and professional critics. Also, it published image and

text for the page – photo pieces as they were known. Your bibliography attests

to your regular writing in different forms for Undercut. Is there anything you want to add to this?

Lis Rhodes:

Yes – I think that Undercut was

a very significant development for the LFMC and thanks to you and Michael

Mazière for all your work as editors.

Nina Danino:

We have spoken about the influence of poetry, artists’ writing but

was this theoretical or critical context also important to you?

Lis Rhodes:

There are many ways of considering theoretical and critical work

and writing on film and art. Some I find very useful – but a quick glance at

the bookshelves a few titles remind – like Review

of African Political Economy

(1984), Women Take Issue (1978), Manushi, In the Shadow of Islam The Women’s Movement in Iran (1982), Women on War (1988), Feminism and the Power of Law (1989).

All strikingly relevant still.

Nina Danino:

In the interview with Jenny Lund you discuss whether making

oppositions between structural/materialist film and personal expressive

filmmaking is problematic in itself and as we can’t get away from the LFMC as a

dominant logos.[38]

You say that you agree, that the oppositional way of viewing is problematic in

its reliance on the conventions of the objective and subjective, and that a

structural/materialist can surely be visionary and personal.

It was a question which was

important in the 1980s too. My experience of the LFMC was that structural film

and positivist approaches were still dominant and there was no place for the

subjective. It was a more purist time, although it was diverse as we have said,

it excluded narrative, representation and the subjective. What were your

feelings in relation to your own position as a woman within the 1970s modernist

avant-garde and the legacy of structural film at the LFMC – was there a place

for it?

Lis Rhodes:

I have

never thought that there was no place for the subjective – as we have already

discussed. My question is simply the divisive proposition that the objective

has a history of expropriation by misogyny. Today this is a known problem with

artificial intelligence – producing algorithms that are from a particular

viewpoint. The theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg suggested in 1927 that

measuring anything is uncertain – it is impossible to measure anything without

disturbing it.[39]

Nothing is unconditional – the subjective is in continual flux with the

objective.

Nina Danino:

Yet representation was an urgent feminist necessity, so how did you position your work as feminist practice in the debates on representation? Did you feel, as Annabel Nicolson says, ‘that the male modernist avant-garde was a natural ally’?[40]

Lis Rhodes:

No – I don’t think that – but I did think that the positioning of

women was a world wide problem – not confined to the LFMC. If representation

was an urgent feminist necessity then the work I have done tends toward

analysing the causes as to why there is misrepresentation of women – which

certainly needs to be made apparent by as many women as possible – from many

different experiences and times.

Nina Danino:

But there were different positions weren’t there? Some felt it was counterproductive to define cinema by its category women. Some women did not want to be defined by this category. Barbara Meter in ‘Across the Channel and 15 Years’ in Undercut magazine in 1990, argued that women were making ‘just as fine structural films as men’ but she admits that she had experiences which still placed her as marginal.[41]

At the RCA Film School women filmmakers of my generation, Lucy Panteli, Joanna Woodward were trying to marry structural non-representational forms with the need to represent but the subject had to be left out of it and this became again about the male dominated objective means of production. The women’s issue of Undercut in 1985 dealt with this question of representation.[42]

Did you make Light Reading with the

intention of challenging this lack of representation and figuration in the

avant-garde through a female specific perspective?

Lis Rhodes:

I made Light Reading to challenge the structures of language in their

effect on and misrepresentation of women. Would it not be wise to re-think the

grammar that forces the separation of objective to subjective – your question

shows the results of this misogynistic divide. A female specific perspective is

fortunately an unlikely occurrence – women have many different lived lives. I

hope that I write from a perspective of a feminist.

Nina Danino:

Did you want your work to engage with a women’s feminist

experimental film? Perhaps it wasn’t called that.

Lis Rhodes:

I don’t think it was called

that in the 1970s.

Nina Danino:

From the 1980s you taught at

the Slade and at the RCA, including myself. Did you also meet artist Sandra

Lahire at the RCA Environmental Media?

Lis Rhodes:

I began teaching at the Slade in 1978 and the RCA in the 1980s. I

think I met Sandra at Saint Martin’s School of Art and then at the RCA. She

played the piano in Just About Now

(1993). We met and discussed work often until her death. Sarah Pucill – her

partner in the last years of her life – was with her in King’s College Hospital

when I saw her that last time. Maria Palacios Cruz and Charlotte Procter at Lux

have recently digitalised and archived her work, which is very important.

Nina Danino:

In the 1970s to the 1990s, the culture of theory and study

supported my work. Film theory had a big influence on filmmakers – but one had

to interpret it, not just apply it. The key avant-garde film theory was only

Peter Gidal’s theoretical writing as such. However, in the 1970s and 1980s

there was a lot of writing on film theory from the new disciplines of Film

Studies on the Hollywood system mainly. Feminist scholars such as Mandy Merck

and Annette Michelson were writing about women’s films in Screen and Camera Obscura.

Undercut was the only journal

focussing on artists’ experimental film. It provided a connection between

experimental film practices, critical/theoretical writing and artist’s writing

as we said. Critics like Gillian Swanson and Michael O'Pray were in Undercut and also wrote for Screen – so although there were film

sectors there were also connections. Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey were

filmmakers and theorists. In Britain the theoretical context for film practice

was highly active and these areas of practice created a connected culture of

film, theory and practice, study and so on in the context disciplines of

psychoanalysis, post structuralism, critical theory etc.

There was the beginnings of

the study of woman’s film. Filmmaker and writer Bev Zalcock programmed women’s

experimental films at City Lit (an adult education college in London). The

essay ‘Whose History?’ in Film as Film:

Formal Experiment in Film 1910–1975 (1979) which is republished in your

book Telling Invents Told (2019) is

the locus of invisibility for women. We have spoken about the influence of

poetry, but do you recognise or relate to parts of this context of theoretical

or critical activity which was important to your work?

Lis Rhodes:

I don’t

think that my work was particularly engaged with film studies or film theory.

Teaching at the RCA and the Slade was in response to the work of individual

students (who were making films, videos, writing and performance works) and

group discussions. There were lively women’s groups at both Schools.

In 1975/76 while I was

organising the programmes for the LFMC’s cinema – I screened Marc Karlin’s Nightcleaners (1975) and Derek Jarman. I

seem to remember Peter Wollen, Peter Gidal and Malcolm Le Grice held a

discussion on structural/material and narrative approaches to filmmaking. Camera Obscura also gave a presentation.

Laura Mulvey and I both wrote individual introductions to Lucy Reynold’s recent

book Women Artists, Feminism and the

Moving Image. So, I was familiar with the issues you mention.

Nina Danino:

Did you engage with feminist debates and psychoanalytic theory,

which was dominant to the 1990s?

Lis Rhodes:

Not in the sense that I

think you mean – but this was clearly on my mind as I wrote the last line of A Cold Draft (1988):

the humming grew so loud

that the censors knew

disorientation had to be

diagnosed

she was certified as insane

a traditionally normal act

it happens - here - all the

time

[43]

The

questions of feminism – how and why we think as we do – are never absent in the

making of work. The questions of colonial destabilisation / theft and

neoliberal economics have proved disastrous for women in many countries. During

the 1990s my work was concentrated on the European US break-up of the Federal

Republic of Yugoslavia and the 1991 war in Iraq – as in Just about Now (1993) and Running

Light (1996), which I returned to in the mid 1990s. I returned to the

recordings I made with Mary Pat Leece in North Carolina in 1985 because I

wanted Mary Pat to see the work I made from them before she died. In one of our

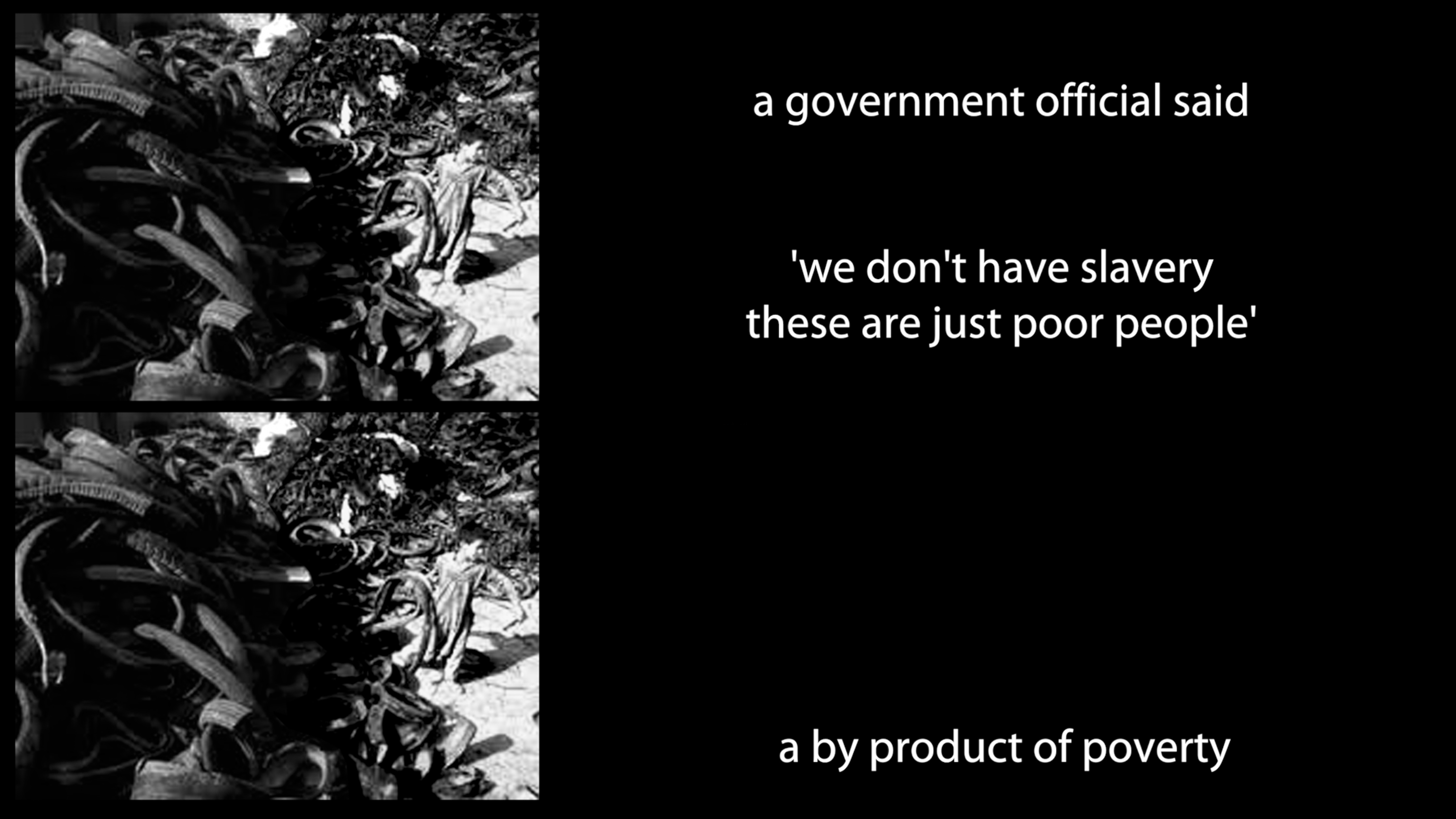

recordings – this is spoken by a local lawyer – she said, ‘I mean why is there

slavery? Why are people held against their will if there's not something?’.

The film Running Light (1996) was an attempt to

understand the system that permitted such practices. This of course connects to

Ambiguous Journeys – a terrible

iteration of now – the conditions faced by migrants, particularly those without

papers.

Nina Danino:

The mirror in Light Reading

is a motif which recurs in feminist deconstructive action on the male gaze, for example, the opera heroine in

Thriller (1979) by Sally Potter, which was a big hit.

Were you using point-of-view sight lines in Light

Reading to de-construct the gaze but also ‘to fragment the narrative space

for the purpose of constructing representations of an internal state’?

The theory of the gaze in

cinema and Laura Mulvey’s woman’s ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ influenced counter

visualities in the feminist films. How did feminist film theory inform your

work? Is the theory of the gaze something that you engaged with? Did you want

the viewer to view Light Reading

through the theoretical framing of the sexual politics of the male gaze? Or is

it to be experienced structurally or to be about perception? Were you wanting

to use the conventions of a visual lexicon to construct or draw us into an

active female gaze?

Lis Rhodes:

As I stress, I was dealing with language – her voice – the

knowledge she carried – unheard. I was surely aware of the critical questions

on female representation. To listen – to hear her – was the reason that only

the voice is heard in the first minutes of the film. This interestingly

prevented it being shown on television. The image in the compact mirror occurs

more than once and represents both genders.

Nina Danino:

The

discussion goes to experimental film culture in the 1980s and 1990s and the

exhibition networks and feminist film and organisations. What was it which made you decide to take the step from formal

structural concerns to prioritise social feminist centred concerns and

political activist filmmaking? What made you move away from the male dominated

LFMC (perhaps the answer is there!) to more social/ist feminist centred

concerns and political activist filmmaking?

Lis Rhodes:

On 30 April

1978, 100,000 people marched six miles from Trafalgar Square to the East End of

London for Rock Against Racism, an open-air concert in Victoria Park.[44]

Many arrived running to catch the performance of the Clash. I was there –

unforgettably so. Obviously, the experience of the Hayward Gallery exhibition –

Film as Film –around that time was

also critical, plainly indicating the need to found Circles. The positioning of

cruise missiles on the [Royal Air Force] RAF Greenham Common in December 1982

moved 30,000 women to surround the base holding hands, and Pictures on Pink Papers was in the making.

Nina Danino:

How did you engage with the

emergent feminist or women’s cinema of the 1970s and 1980s in London? You

became a founder of Circles in 1979 together with Annabel Nicolson and Felicity

Sparrow, to focus on programming and distributing women filmmakers in response

to the lack of visible women filmmakers and produced a catalogue and toured the

programme Her Image Fades as Her Voice

Rises.[45]

The idea of being heard is clear, but is why was the image fading?

Lis Rhodes:

It was so essential that if

there was to be an understanding of women artists’ film, video and performance

work, that we got a distribution network going. As you have mentioned, there

were feminist publishers and contemporary magazines doing similar work in

literature. Cinema of Women was already established. One of the students I

taught at Croydon College of Art was involved and Felicity Sparrow and I had a

very good meeting with COW to talk this over.

The first two catalogues for

Circles were just simple printed pages which we paid for. Then there was a

pamphlet titled Her Image Fades as Her

Voice Rises (1983) to assert the importance of women’s voices. The

tradition of narrative film that Alice Guy initiated in 1896 with her first

film La Fée aux choux, appears to be

drawn from the theatre. She used sets and actors to represent visually the only

form of cultural expression in which women were allowed to play a major part –

the writing of fiction.

Nina Danino:

Why did you position your

work in favour of more political filmmaking rather than abstract avant-garde

and experimental film?

Lis Rhodes:

There is nothing more

political than the deliberate absence of women from history, the structure of

language, economics, philosophy, mathematics and musical composition. Light Music (1975) was made because of

the apparent absence of women composers in European Classical tradition.

Still from Lis Rhodes,

Pictures on Pink Paper (1982).

Copyright Lis Rhodes. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Alison Butler says that

filmmaker Maya Deren turns to anthropology and the minimalisation of personal

identity of her presence on film as an escape from her ‘hall of mirrors’.[46]

This seems to signal a fading of inscription. The personal pronoun is

minimalised in the work after Pictures on

Pink Paper and thus presence of the self. Did you reach a limit as to how

far you wanted to take the personal in order to adopt a more overtly activist

political expression?

Lis Rhodes:

Your question suggests that possibly the personal is separable from as you say, overtly activist political expression – indeed they are frequently forced apart – but the one cannot be divided from the other. This does not mean necessarily that the one is other. I am certain that personal is always present – but in my work the personal pronoun is used as inclusive as I have already explained and as Felicity Sparrow wrote in Her Image Fades as Her Voice Rises (1983) ‘“She” is spoken as a multiple subject -– third person singular and plural.’[47]

she could feel the

contamination

but inquiry is known to be

revealing

the censor would redefine

reason – again

[48]

Nina Danino:

Since Pictures on Pink Paper,

a film I personally like very much because of its sensuality, the voices of the

country women talking and questioning their surroundings which is a local

topography, has receded. Your work since Pictures

on

Pink Paper to your most recent

film is characterised by the dominance of political

activism. Ambiguous Journeys deals

with political topics. Of course these are feminist concerns but do you think

that it needs an inscriptive register to be a feminine language?

Lis Rhodes:

In Ambiguous Journeys

the writing I wrote is literally inscribed in the images – timed to the voice –

punctuated by sound. Whether there is a ‘feminine language’ I doubt. As a

feminist – I work – as best I can – as a feminist.

Nina Danino:

Dissonance and Disturbance is the title of recent exhibitions and of the film of 2012, which frame the curating, interpretations, readings and viewership of the work. In an interview with you, Anna Gritz says that your work ‘is a testament to her enduring desire to reactivate and reinvent cinema as a viable expression of protest’.[49]

Lis Rhodes:

Dissonance and Disturbance was the title of a film