Part 3 (of 6)

Lexicons of Introspection: 16mm, symbolism, editing

Jayne Parker in conversation with Nina Danino (2020)

Photograph of Jayne Parker (2003) by

Simon Parker. Courtesy of Jayne Parker.

_______________

Shaped from an online conversation and subsequent emails between the artists during and after the first COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in the UK, this text involves a dialogue between Jayne Parker and Nina Danino. They later revisited their discussion and edited the transcript in 2023 and 2025.

________________

Taking Jayne Parker’s close work with 16mm film as a starting point, the discussion below is contextualised by an essay on the ‘The Artist as Filmmaker’ by writer and critic A.L. Rees,[1] published in the catalogue for a retrospective show of Parker’s work in 2000.[2] It discusses the visual language of her experimental films as a form for dealing with ideas at the borderline of naming through the use of a visual vocabulary.

The conversation examines Jayne Parker’s

chosen lexicons of gesture, symbol, performance and actions. Starting with a

discussion of her film The Oblique

(2018) and with the work in the exhibition Still

Life by Lisa Milroy and Jayne Parker at A.P.T Gallery in London (2018), it

doesn’t go into interpretation, instead it engages with each films’ own visual

language, and the grammar that is particular to them. Their dialogue doesn’t

try to decode the meaning – this isn’t possible, as the signs in Jayne Parker’s

films can’t be fixed. There are oysters, eels, fish and actions such as wiping

the mouth, diving and washing. Often, the protagonist doesn’t speak, she is

silent. Are these works trance-films, quest films, psychodramas? This

conversation explores the language of the films, which is one of precision,

economy, control and focus.

Editing plays a prominent role in Jayne

Parker’s films, in whose work continuity in editing is transferred to

experimental film, where there is a disjuncture that doesn’t conform to the

standard. In this context, the approach of Maya Deren provides an apt parallel.

A filmmaker known for surrealism and symbolism but also for working as an

editor in Hollywood, Deren wrote precisely on the art of editing. In her

writings on creative cutting she says that ‘the function of cutting can be said

to be that of the thinking, understanding mind’.[3]

She

writes that editing creates, ‘the meaning, the emotional value of the

individual expressions, the connection between individually observed facts, is,

in the making of the film the creative responsibility of cutting’.[4]

Editing is not secondary to the poetics of symbols in the artist’s oeuvre, but

this and the wider conversations in this series discuss how it is part of

signification. They discuss visual language as having the impact to convey

intensity in relation to Jayne Parker’s work as part of the precision and

economy of shots, framing, camera and the cut, in order to convey that which

has no ready name.

________________

Please note that the opinions and information published here are

those of the speakers/authors and not of LUX or the wider research team and

institutions involved with their funding, transcription and publication.

Published online by LUX, London (2025)

Editing and research: Claire M. Holdsworth (2020/2025)

________________

Conversation

Recorded 19 December 2020 (Slade School of Fine Art, University College London)

_____

Nina Danino:

Jayne, it’s nice to see you

and thank you for this conversation. We’re at the Slade School of Fine Art

[University College London], where you are Professor of Fine Art.

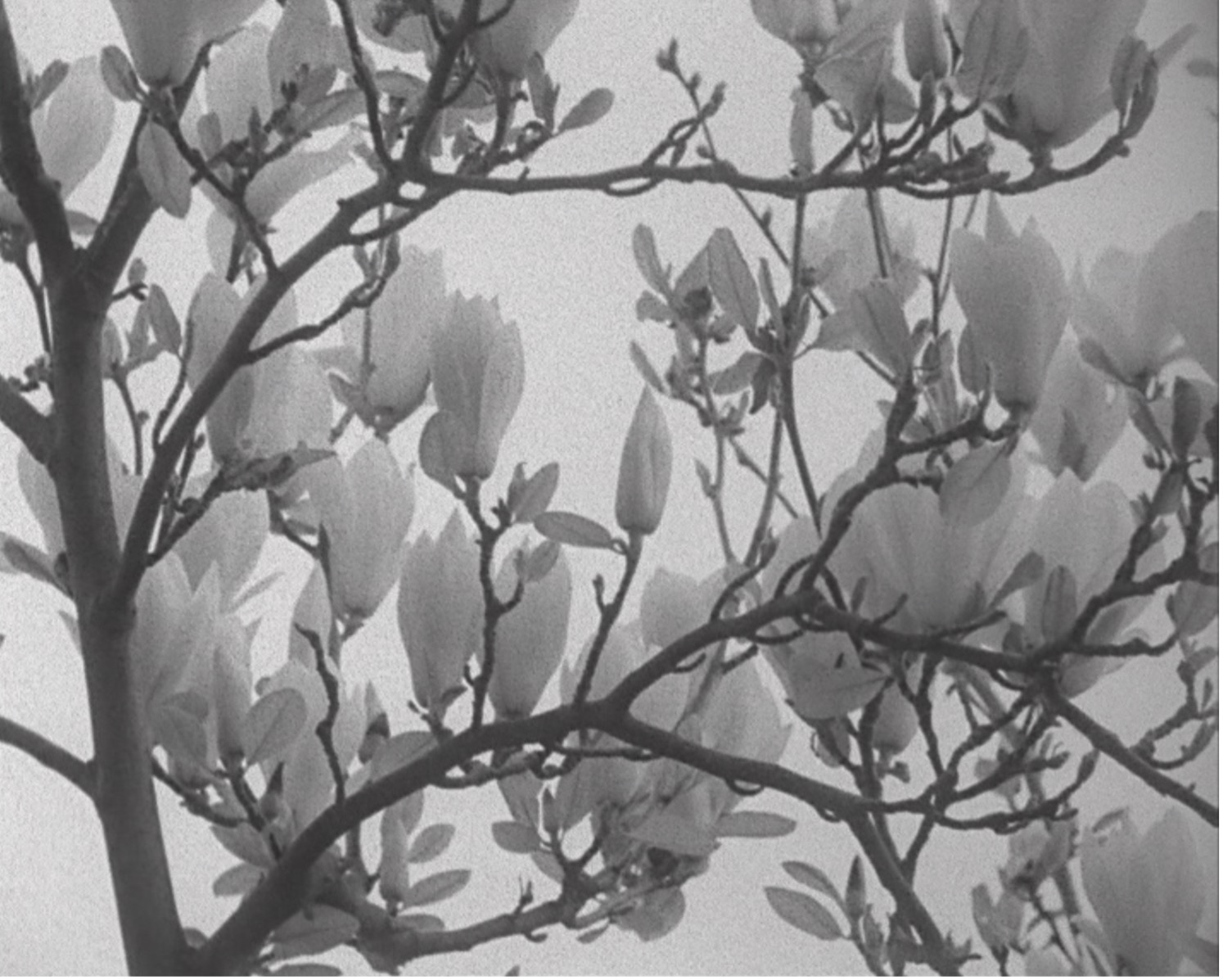

Your film The

Oblique was shown in the exhibition Still

Life at A.P.T. Gallery. It is shot on 16mm and includes images of white

magnolia flowers against a dark night background. It was shown alongside a

series of black and white photographic prints and photograms. Where does the

image of the magnolia tree come from?

Jayne Parker:

It dates from when I moved

into my present home. In the garden there’s a white magnolia tree and the first

year I was there I filmed it at night. It is one of those images that has

become really important to me – filming the tree at night, it felt as if it was

flowering too late. It felt poignant – and it’s a beautiful tree, a beautiful

image. The magnolia tree has stayed at the centre of my work from then.

Nina Danino:

When was that?

Jayne Parker:

Since around 2001. It didn’t

appear in a film until a bit later. I first used the image of magnolia blossoms

in Stationary Music (2005), featuring

Katerina Wolpe, the pianist. It was the first time I used the magnolia. You

know, when you see those closed buds, it’s like everything is on the inside –

and the bud is also like a flame. I think in all my work, things are what they

are, and then they’re also something else, or they point to something else. It

is an image that has stayed central and is still active. Recently, in the last

few years, I’ve been making a lot of objects, sometimes using magnolia wood.

For several years I collected all the petals that fell from the tree and dried

them. I had this idea I could make paper from them, but the petals don’t

contain any cellulose. They can’t bind together without additional material.

Still from Jayne Parker, Stationary Music (2005).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Jayne Parker:

We’re entering this

conversation through materials and photography, through the physical presence

of the magnolia tree on 16mm film. How did you engage with photographing and

also producing photographic prints from it through photograms and the direct use

of the flowers?

Nina Danino:

For some of the prints I use

magnolia petals as negatives, by placing individual petals in the negative

holder of the photographic enlarger in the dark room, which usually holds the

photographic negative. There’s a direct relation between the actuality of the

tree and the image and that’s important. I’ve made a lot of photogram work with

the petals, and the buds as well – it’s very direct, as well as being one to

one in scale.

For the film Stationary Music, I shot on 16mm

negative. With the photographs that you saw in the exhibition Still Life (2018) there’s no negative

involved, it’s purely the petal itself which is used in place of the negative –

in a way the petal becomes a negative. With the photograms, the magnolia petals

and flowers are laid directly on the photo-sensitive paper. I have quite an

uneasy and difficult relation with photography itself, as opposed to

filmmaking. I always feel I am in danger of deadening an image when I take a

photograph. It’s the sense of movement of film that’s always been so important.

Even if I’m filming something that’s still, it’s ‘in-time’. Standing next to

the Bolex camera and counting the seconds of film footage as they run through

the camera – there is something about the act of filming and duration that

creates meaning.

Jayne Parker:

The writer and critic Al

Rees writes in ‘The Artist as Filmmaker’ – which was published in the catalogue

for the retrospective show, Jayne Parker

Filmworks 1979 – 2000 at Spacex Gallery in Exeter in 2000/2001 – that the

films ‘deal with sensations and ideas at the borderline of naming’ which

suggests a subjective aspect.

Nina Danino:

That catalogue accompanied a

Film and Video Umbrella touring show, co-commissioned with Spacex Gallery, and

accompanied that exhibition.

Jayne Parker:

It would be good to discuss some of your films through ‘their own subjective routes’ – K. (1989) is a kind of self-portrait.[5] In K. you’re facing the camera naked and perform a knitting act with the heavy entrails of an animal. You had previously done performance to camera in Almost Out, in 1984 where from memory, you perform naked also standing but in a video suite and conducting a series of exchanges of possibly unanswerable questions and declarations to two other participants who engage with you. One is a middle-aged woman who is also standing naked and patiently answers you standing in the glare of a studio and the other is a man who is clothed and appears in a two-shot with you in the video suite. These interrogations and exchanges take place over a long period of 100 minutes which makes it a durational video work.[6] I posed formalist questions to you about this video for Undercut special issue on women’s work.[7] The LFMC included critical confrontation and questioning but from a position of careful consideration of the work. 16mm has been your main medium of practice and K. is a 16mm film where you film yourself performing to camera. What made you take that step in K.?

Jayne Parker:

It was just pragmatic

really. I couldn’t find anybody to do what I wanted them to do. In that film

it’s as if I’m taking out my intestine, eviscerating and knitting it (using my

arms). I was symbolically taking things out that I felt weren’t mine and then

making a new order through knitting. It’s a very literal film. In fact, a lot

of the films are very literal; they are exactly what they are. I knew I could

do it. I wasn’t fazed by dealing with the intestine, although it was

challenging. It was because of not finding somebody to do it, that I was in

that film.

Nina Danino:

How did you prepare for the

performance?

Still from Jayne Parker, K. (1989).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Jayne Parker:

I always prepare a lot

before filming, although recently, maybe in the last decade, if I’ve wanted to

film something I’ve just filmed it. Now I have a cupboard full of film that is

waiting to find its purpose. It’s like I’m hoarding in a way and that’s not

good: it’s potential without becoming something. I’m slowly working my way

through it, finding a way to bring structure to it. I would always plan before

I filmed something. I’d take still photographs with a 35mm camera and later

used a small video camera, although that could be problematic as the video lens

on a camcorder rarely equated with the parameters of 16mm prime lenses.

I never had a storyboard but

I did have a list of shots I wanted to film. I could never imagine how

something would go together until I was editing it, until I saw what the

material could do. So, I made sure I covered everything, in order to give

myself choice with the edit. It’s not a very economical way to work but I’m not

very good at visualising something until I see it. In fact, I’m really only

filming things that I’ve seen or think I’ve seen, rather than something that

has been constructed purely from the imagination. Through editing, the images

and actions are put in relation to each other, and that’s where the leaps can

happen.

Nina Danino:

You mention ‘finding a way

to bring structure to it’ for K. The

camera is on a tripod, it is very precisely shot for editing so that your

actions can be reconstructed. Maya Deren calls this ‘shoot to cut’. She sees

this as an essential part of economy, both so that shots aren’t wasted but also

economy of thought by having ‘the final cut version of the film in his (sic)

mind’.[8]

There are two parts. In one you perform the knitting of a garment with the

intestines of a cow and in the second

part you are seen diving several times into a public pool. Both are shot on

16mm in black and white. Do you work with the final version in mind?

Jayne Parker:

The two parts were always

intended to go together. For me, part one was about taking something out in

order to make space for something new and part two was entering into a new

space – or attempting to enter into a new space. I saw them very much in the same

light, one naturally following the other. I remember doing a test with colour

film to see if it would work well in colour. The test in itself looked very

beautiful. The intestine was a soft grey-pink, with white fat. But that made it

look more like a horror film, and I wanted to take any horror or disgust away

from the image with the intestine. I wanted the action to be something that I

could just do, just like that; as if it wasn’t a big deal to do it.

Nina Danino:

In K. were you thinking about yourself as a performer to camera?

Jayne Parker:

I was just doing the action.

I wasn’t particularly thinking of myself as performing to camera, although of

course I was aware of the intended framing.

Nina Danino:

Where did the choreography

of the actions for the camera come from?

Jayne Parker:

They came out of the action

itself and I was just carrying out the action as well as I could, for example,

in K. I was just knitting. With the

people that I filmed in my earlier films I was drawn to them because they used

their hands very well and I knew that whatever I asked them to do they would do

it in an adept or particular way. It is the same with the musicians in later

films. There’s a quality of concentration that intrigues me and I want to be

where they are when they’re playing or performing. There might be gestures that

they do that are unconscious. It was interesting filming the musicians because

they would usually make the same gestures at the same points in the music.

I find nuance really interesting and that’s what has

always drawn me to people, to their presence when they do things. I think one

of the difficulties of being in my own films is that I also want to be behind

the camera. But I can plan for it. However, people don’t see things like you do

yourself, and that can be difficult sometimes. One of the main things that came

out of being in K. was the importance

of witnessing myself doing things and doing things that I found difficult or

challenging, like the diving, that wasn’t easy. I had to make myself do it.

Working with the intestine was difficult too. It was heavy and incredibly cold

because of course it had no life in it. I think there are physical challenges

that affect the way I do things or perform. If something is heavy you will see

the effort.

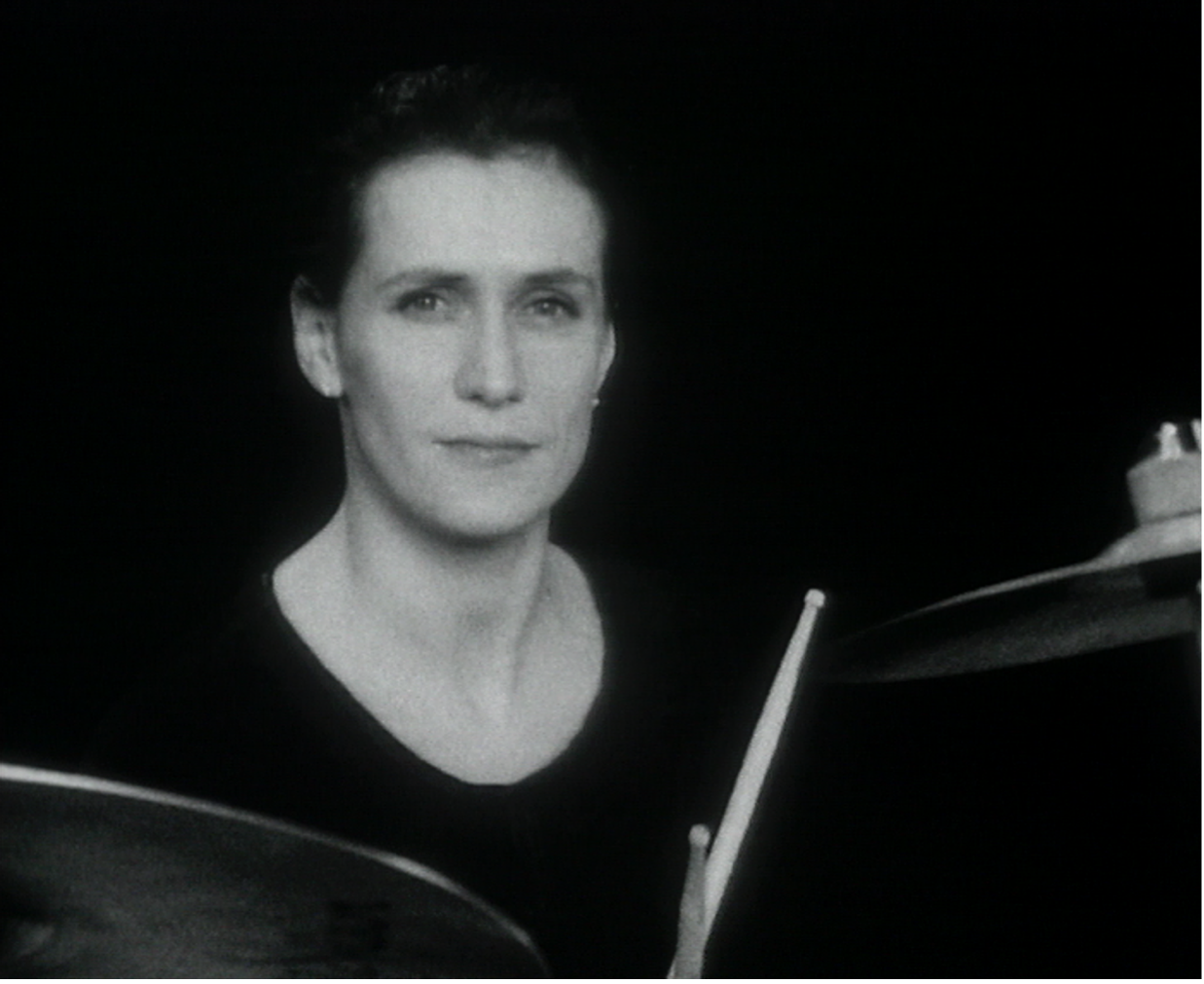

Still from Jayne Parker, Anton Lukoszevieze in Blues in B-flat (part of Foxfire Eins) (2000).

Copyright Jayne Parker. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Were you interested in films where the filmmaker is in them as a character or performer such as in ‘Symbolist’ films (as Rees discusses in the catalogue essay) or taking a ritualist aspect in the quest film or the trance-film such as Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet (1932).[9]

Jayne Parker:

Yes, I’ve always been

interested in such films. I first started making films as an undergraduate

student at Canterbury College of Art where I was taught by Pierre Attala, who

was a great teacher and a strong influence. Filmmaking was part of complementary

studies, it was programmed for half an afternoon a week. It was the first time

I met somebody who didn’t ask me why I wanted to do something, but just said

“Oh, let’s see, how can you do that?” It was very facilitating and liberating.

Nina Danino:

Would you like to say more

about him?

Jayne Parker:

As I remember, Pierre’s

expertise encompassed filmmaking, theatre and writing. He had a scientific

background and a great interest in expression, a broad and rich knowledge base,

which was practical as well as intellectual. I considered him a good friend and

mentor, an important figure, both while I was at college and in the following

years.

Nina Danino:

He’s the interlocutor in Almost Out, is that right?

Jayne Parker:

Yes. We worked on that

together, on those two videos, Almost Out

(1984) and En Route (1986), they were

made in collaboration. Probably, everything that I think about film, comes from

my time as a student at Canterbury College of Art.

Nina Danino:

You have always acknowledged

him as a key mentor and influence in your work of the time.

Jayne Parker:

Yes. There were three of us

who went to those film classes. Claire Winter, a fellow student, was one of

them, she appeared in my films Free Show

(1979) and RX Recipe (1980) but I was

the only person who continued making film in my year. For me, not having to be

good was another aspect that was important, because I always felt I had to get

it right and here was a situation where I didn’t have to prove anything. Even if

something didn’t come out very well, there was always a way to work with the

material – it fostered a good attitude. Thinking about it now, Pierre’s

scientific background brought a different discipline and approach, which was

very liberating.

Nina Danino:

Did Canterbury have 16mm

film facilities?

Jayne Parker:

Yes, there were basic 16mm

film facilities. I remember there were three 16mm cameras, one of which was a

Beaulieu. The editing was picture only and done at a desk with a Murray viewer

and two re-wind arms. There were 16mm projectors and I recall adding the sound

directly onto the magnetic strip of the final print through the projector. The

very first film I made was about someone living in a greenhouse. I took the

camera back to Nottingham and filmed in my Dad’s greenhouse. For some reason I

thought that the tripod could only move at right angles, left-to-right or

up-and-down – I didn’t realise I could move it freely, for instance that I

could follow something. I don't know what happened to that little bit of film,

but it's the very first thing I ever did – I would like to see it again now.

Then there was a film called Show Them a

Leg and The Trumpet Quivers, (1978) which was followed by In Some Rooms it Didn't Matter if I was

There or Not (1978), neither of these films are in distribution. Free Show (1979), I Cat (1980), RX Recipe (1980)

were all made in Canterbury and are held in the archive at LUX, who distribute

them. I made I Dish (1982) and Snig (1982) at the Slade, where I

studied after Canterbury.

Still from Jayne Parker, I Dish (1982).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Can you talk about how you

developed the symbolist vocabulary of the films you made at Canterbury and

later? Snig, I Cat, The Cat and The Woman,

A Cautionary Tale (1987), RX Recipe.

They're populated with creatures, cats, fish, eels. With actions and gestures

of eating, bandaging, washing and actions made by collaborators and performers.

Jayne Parker:

I can try. When you asked

that question, I remembered reading a book about fish, while I was a student in

Canterbury. In this book, I can’t recall the name of the book, it said that

fish didn't experience pain because they didn't have the part of the brain that

corresponded to the human experience, which even then felt unfounded and

untrue; fish do experience pain. Also, I had ideas about fish being in the

earth, and things not being in their usual place, and I think that has probably

continued – things being out of their usual element. For instance being

underwater in Crystal Aquarium.

Nina Danino:

You do startling things like bandage them or take care of these creatures that […] seem to belong to a personal bestiary.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, or creatures that are

dead but are somehow still being treated as if they’re alive, for instance the

conga eel in RX Recipe. The film is

based on a recipe from the culinary classic Larousse Gastronomique. In the film, there's nothing the eel can do to fight

against its condition – I think of it as inert and being force fed. It can't be

[…] I don't know […].

Nina Danino:

It can't be animated

Jayne Parker:

Yes, it can’t be animated.

The eel is an image that can be taken as a sexual or bodily reference, either

symbolically or through standing in for the body. It is out of proportion

because of its scale. There is a wryness there. Incidentally, the conga eel was

lent to me by a fishmonger, who took it back and smoked it after the filming.

Thinking of this now, it adds to the awfulness of the eel’s condition.

Nina Danino:

You hold the eel and you

caress it. It is unsettling and at the same time cryptic.

Still from Jayne Parker, RX Recipe (1980).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Jayne Parker:

There is something about

absurdity and the unexpected at play, and also the beauty and strangeness of

creatures. For instance, the live conga eel in The Pool (1991), there is something about the way its gills open

and close in the footage. It is mesmerising. I mean they are terribly fierce

creatures. I read a lot about eels and their journeys, about elvers and other

types of eels, and the fact that no-one had ever seen them mate, although it is

known that they mate in the Sargasso Sea. I became very interested in the

hiddenness of this, the mystery, not everything can be known, but this was over

thirty years ago. Perhaps it isn’t a mystery now […].

Nina Danino:

Were you wanting to develop

your own symbols? Could you say something about that?

Jayne Parker:

I think I really liked

using, and still do, an image that is exactly what it is. For instance, an eel

is itself, but can also be seen as a symbol. It depends what's happening to it

in the film. If I film a fish, it could be male or female, depending on what

the image is and how it’s placed in the film, so you can never be sure about

what you're seeing, or where it's going to take you. It's quite a line to try

and walk, between something that's so obvious and yet is working to define its

own meaning.

Nina Danino:

Shifting its meaning and

given symbolism.[10]

Jayne Parker:

Yes. If I think about it

now, I think of it as a refusal to be defined. Images can be very slippery,

they don’t always do what you think they are going to do. You can’t assume

meaning. Even with the intent to make a film about a certain subject, when you

get the footage back it is as if you are seeing it for the first time. I've

never wanted to make imagery do something, rather I want to be open to what it

is.

Nina Danino:

Are you discovering how far

you can take images, also not trying to impose too much on them?

Jayne Parker:

Yes, often I might be doing

things in order to confront something, to try and see something, to try and

make sense of something, to find meaning. I think it's that third thing that

emerges when you put two images together. It is something that can't be said

verbally, that can't be articulated, that carries the meaning.

Nina Danino:

Symbols are fixed signs, but

an eel could be a phallic symbol or it can be a metaphor for something slippery

like meaning. But if they are cryptic, they need to be unlocked and we might

not be able to read them. Is it about finding a symbolic language on that

borderline which keeps an open communication where it communicates to the

viewer also?

Jayne Parker:

Yes. When I think about

films I’ve seen where I resist engaging, it’s those where, as a viewer, I'm not

given any space, where no stone is left unturned, for me to actually enter into

the film, to be stunned by an image, or to enjoy the experience of not knowing.

Nina Danino:

At the same time, the films

seem to be communicating something urgently that is not directly communicable –

a certain introspection. Yet there is a lot of control in this language, in the

precision of performed actions, framing, editing, therefore they also

communicate through this language of precision in how you film objects,

gestures, actions. Al Rees points out that ‘psychodrama grew as an avant-garde

genre’[11]

where the artist is the protagonist in their own film and performs rituals or

roles to explore and gain interior insights into themselves such as in personal

quest films mentioned earlier.

Jayne Parker:

There are many films I like a great deal that I have seen over the

years, for instance the films of [photographer/filmmaker] Jean Painlevé, and

particularly [artist and filmmaker] Maya Deren’s At Land (1944). Also Robert Bresson’s films, his film of Cocteau’s

script Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne

(1945) and the films of Carl Dryer particularly Odette (The Word) (1955) to name but a few.

When I was at Canterbury

there was a film club and we saw art house movies, but no experimental films. I

managed to write my dissertation on the artist Andy Warhol and his films,

without ever seeing an Andy Warhol [artist] film. I read about them. I remember

going up to London to see Eraserhead (1977)

by [director and artist] David Lynch. I actually didn’t see any experimental

films until I was at the Slade where I was lucky to be taught by Chris Welsby

and Lis Rhodes and I started going to the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC].

In 1984 I was awarded a

fellowship at North-East London Polytechnic. Filmmaker David Parsons was

running the film area then, and the artist John Smith taught there. Al Rees

came in every Friday afternoon and showed films. It was wonderful because he

just showed them. We just sat and watched films for a couple of hours. They

weren’t heavily contextualised or introduced. We watched and watched and

watched and that was very inspiring. I saw a lot of films then.

Nina Danino:

Was there a particular film

or films that stayed with you or became important?

Jayne Parker:

I particularly remember

Steve Farrer’s Ten Drawings (1976).

That's always stayed with me. It demonstrates so beautifully how optical sound

works and the relationship between the drawn and its corresponding sound, and

how a film can be made without a camera.[12]

I think there is something too about the process of the film’s making from the

rectangular drawing to the linear film strip that captivated me – it made me

think about structure.

Also, early films by Kenneth

Anger, in particular Fireworks (1947),

and early Brakhage such as The Way to

Shadow Garden (1954) and Mothlight

(1963). When Al [Rees] screened Mothlight

at NELP [North East London Polytechnic] the film print was passed around so we

could see the images of the moth wings and seeds that Brakhage had laid along

the original film stock to make the film. Often things I remember hold a

reference to the materiality of film. Another example of this is Malcolm Le

Grice’s Yes No Maybe Maybe Not (1967) where both the film negative and

positive are superimposed, producing a cross-over area – as in a Venn diagram.

I like to think of this third space, where there is neither positive nor

negative.

Nina Danino:

They would have been shown

on 16mm.

Jayne Parker:

Yes. That was the first time

I really began to see things. Then of course being in London and going to the

London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC]. In retrospect I can see that the films I

remember, that stay with me or that I admire, are often the ones where I am

drawn to the makers’ ways of working, ways of thinking. Often, it's the way of

thinking. I like structuralist film for the ideas. It's that which attracts me

to experimental music too. Not because I necessarily get pleasure from

listening, it can be very challenging, but because of the way the composers

think about structure. Even though my films don't obviously explore structural

concerns I like to think about such things, particularly in relation to the

materiality of film.

Nina Danino:

The London Film-makers’

Co-op [LFMC] was diverse in the eighties but structural film from the seventies

was strong with its focus on the material of film and on film as medium

specific practice.

Jayne Parker:

That reminds me – I think

things are coming back as we are talking. When I was at the Slade, and I might

be getting dates wrong, I always felt out of step with what was happening

within film, with structural filmmaking and the New Romantics.

Nina Danino:

The LFMC cinema in the

eighties showed lots of different works by artists but there was a trend

towards Super 8 by artists like John Maybury, Cerith Wyn Evans and others who

were connected to the Co-op such as Cordelia Swan, Jo Comino. There was a group

who associated themselves loosely as New Romantics. It seemed to capture the

imagination of artists. Michael O’Pray’s writing championed it. In the eighties

there wasn’t new writing on experimental film and the avant-garde as a

movement, as Michael O’Pray realised, had ended. So, experimental film exploded

into different modes but it had no over-riding theory as the previous

generation had had. Michael O’Pray wrote about the dominance of aesthetics in

film and curated video programmes.[13]

Pandaemonium was curated by Michael

Mazière. But round about 1988 the YBAs began to exhibit in the London art scene

[Young British Artists]. In the nineties, Michael Mazière describes how the two

camps never connected despite the critics’ and curators’ efforts.[14]

Some of those artists connected to the LFMC, some peripherally, but some

closely, moved into the gallery.

Jayne Parker:

I felt I didn't fit in; I

didn’t relate to the ideas. And I was shy. I felt outside, whilst wanting to be

on the inside. I didn't use the LFMC facilities because it took me so long to

film anything that I didn't want to take a risk with the processing in case

something went wrong and I lost the film. I just wanted to take my film to the

lab. In many ways the films for me were made in the editing and I needed the

negative development to be guaranteed.

Nina Danino:

That's right, because at the

LFMC you could use the processing machine yourself or it depended on who was in

charge of doing it, Peter Milner was a very good lab technician, the baths were

run on certain days of the week but it could be unreliable because the bath

might not be run and if you needed your rushes for a deadline it was better to

go to the professional laboratories such as Filmatic on Colville Road. Also,

there was always that concern that if something did go wrong for example,

under-developing the negative because the bath developer had been used too

often or if there was some technical accident you could lose irreplaceable

footage and it was the risk you took.

Jayne Parker:

Exactly. When I found

filmmaking – I was studying sculpture at Canterbury and felt that I couldn't

imbue objects with the meanings that I wanted them to have – there was

something about film that offered this way of working where you could have

multiple strands, imagery, and things could have […].

Nina Danino:

Jayne Parker:

Yes, levels of meaning. For

the first time I felt that, even if I edited something and I didn't include a

shot, it was still there. I didn’t lose anything. There was something about it

still being there even if it wasn't present in the final edit. Working with

film allowed me to imply meanings that I couldn't manage to do through objects

or sculpture. It was this that was liberating for me, the tools of filmmaking

were liberating.

Nina Danino:

Could we then talk about

those tools of filmmaking and your particular film language?

Jayne Parker:

Yes.

Nina Danino:

They're not just tools,

they’re your vocabulary and they’re your language.

Jayne Parker:

My aim is to capture what it

is that I see or think I see, and I don't want to dramatise it through art

direction.

Nina Danino:

You use a static camera,

there are frontal shots and side shots, close-ups, the use of the tripod, the

frame is emphasised. There is a strong sense of the edit and the construction

of making a film. Also, what was it about the 16mm film gauge, because we were

working at a time when video was an option.

Jayne Parker:

I like the fact that there's

a negative. I always film on negative. I have never used reversal. I never used

Super 8 either [8mm film] because I wouldn't have been able to change my mind

when editing without damaging the material. That's what's so wonderful about

the cutting copy, being able to keep track of every single frame.[15]

I'm very good at organising film – not in tidying up a computer, I can't

organise anything on a computer very easily. It's just that I need to see it; I

need to have the material laid out. I used to love the fact that on this strip

of film was the shot of an action, or on this strip of separate magnetic tape

was the sound.

Nina Danino:

The physicality?

Jayne Parker:

Yes, the physicality. It

stays with me, that way of thinking, through the Bolex, through the camera,

through the shuttering, the adjusting of the aperture depending on how much

light there is, and the effect this has on the depth of field, on what is in focus.

I have made works using video, and when I think back I really like the quality

of early video. With the digital there's a lack of substance to it and I find

that troubling. I tried to make the leap into the digital, like a lot of

friends or colleagues have done, but for me it doesn't hold much interest as a

medium itself, although I often finish films digitally because of the sound.

The sound quality of a 16mm film print isn’t subtle enough to adequately

reproduce music that uses a wide dynamic and tonal range. Digital shooting can

be such a slippery medium and inclined to excess. You can just keep on

recording, producing hours of imagery; whereas the economy of film means having

to anticipate something, not knowing what it's going to be like until you get

it back.

Nina Danino:

Well using 16mm imposes a

structure also because the 16mm film roll is limited to either 100 feet or a

maximum of 400 feet at a time which is either is 3 minutes or 10 minutes. This

determines and places a limit to how you plan and organise the filming, whereas

in digital you can film for hours.

Jayne Parker:

I think it's that structure

that really excites me and to be able to try and make something that is

faceted, that has a lot of different aspects or strands. I think of the films

as faceted objects.

Nina Danino:

Yes, 16mm does have a

physical reality as an object.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, absolutely.

Nina Danino:

When I programme a 16mm film

screening at Goldsmiths, it needs a lot of paraphernalia, the film split

spools, different sized film cores, the film splicer in case the film snaps, a

cloth to clean the film. The 16mm cutting room had a set of beautifully engineered

and designed working tools and equipment. I still have my manual 16mm pic-sync

viewing machine although I sold my Steenbeck to Sarah Pucill in the nineties.

Jayne Parker:

I still have a ‘film room’

at home with a Steenbeck and pic-sync, both of which I use for editing. I've

always enjoyed the act of working with film, handling film and being adept with

it, using the equipment, working on the Steenbeck, running the film back and

forth, cutting the film.[16]

Nina Danino:

I love the rhythm of editing

on the Steenbeck which uses the whole body to feel the pace which you don’t

have with digital which is only one finger. I edited Sorelle Povere Di Santa Chiara (2015) to fine cut on the Steenbeck.

Let’s talk about the camera and filming on 16mm. The earlier films are shot on

16mm stock, and perhaps you used a fast film as they are filmed in interiors

and are lit and the image is full of contrast and grain.

Jayne Parker:

In the early films when I

first started using 16mm I never felt I had a problem with depth of field,

probably because I used a high rated ISO film that was more sensitive to light.

The more films I made the less depth of field I seemed to get. Those technical

problems seemed to accumulate – and now there is never enough light, maybe

because I’m filming in more controlled studio situations.

Nina Danino:

In the films of the

nineties, which are performances for the camera, the cinematography is fine

grained there is less grain texture of celluloid film as a material. Is that

because you worked with cinematographers? For example, in Crystal Aquarium and The Pool

where you film underwater.

Still from Jayne Parker, Debbi Figueiredo performing underwater in The Whirlpool (1997).

Copyright Jayne Parker. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Jayne Parker:

Perhaps that’s the reason.

When I worked with a cinematographer higher-end professional film cameras and

lenses were used, which accounts for the finer grain of the films.

Nina Danino:

Crystal Aquarium the camera is positioned around the performance on

low shots, overhead shots, the body of the performer and the camera are always

in a relationship to each other. There is a sequence of low-level shots of the

skater’s skates gliding on the ice – how did you get that shot? Also the hands

of the pianist Katharina Wolpe are so precisely framed for the sequence of

music she is playing in The Whirlpool.

The framing and the performance and cinematography all fit perfectly.

Jayne Parker:

The close-up shots of the

skates were shot away from the ice rink, on a block of ice mounted on a

scaffold, or else I wouldn’t have been able to film as I wanted to. With the

framing of the pianist’s hands, I always worked out where they would be, either

in the air or on various sections of the piano keyboard, and framed

accordingly. The majority of shots are premeditated but there is always space

for the unexpected or if something doesn’t work on the day. It's to do with the

image; it's to do with realising the image. I think if I see something that I

want to film, like you mentioned earlier, there is an urgency, I've just got to

do it.

Nina Danino:

The drive to make a film is

necessary as it’s often the main reason to make it. There are so many hurdles

to overcome so there has to be an urgency to realising it.

Jayne Parker:

Yes. Then that fear – am I

going to be able to capture it? Will I be able to capture it? When you begin

something new, everything is possible. Knowledge and habit don’t get in the

way, and there isn’t the same fear of failure. It's this striving to get something

right – for me it's either right or wrong, there isn't any middle ground, or it

can be the best that I can do.

Nina Danino:

Particularly when you're trying to make a film communicate about experiences that are oblique in some way. To quote Al [Rees] again ‘on the borderline of naming’.[17] Not in a direct way, but that sense of – what word did you use?

Jayne Parker:

The capture.

Nina Danino:

Capturing. Because capturing

is something that isn't just about the images. It’s also about how the film

experience imparts that ‘intensity’.

Jayne Parker:

For some things I've never

been able to capture the quality I wanted. It is interesting that we are drawn

to one take rather than another. When I am editing, I’m asking: ‘What's going

to carry the tension? What's going to carry meaning?’ Some shots can be

beautiful, really lovely and technically fine and all that, but there is

something missing. A lot of footage that I shoot is discarded – maybe because I

am not following a storyboard. I have a shooting script but that's different.

Nina Danino:

The shooting script is the

order of the shots.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, and a set of drawn

images indicating each shot I want to take, such as a wide shot, mid-shot,

close-up, taken from this angle or that angle, and from this point in the

action.

Nina Danino:

Your films look very highly

executed like they have been highly prepared and planned.

Jayne Parker:

I have a drawn shot list –

but not ordered into an imagined completed film. When working with a

cinematographer I draw directions for each shot, because I want the image

framed in a particular way. I learnt the hard way by saying “I want this – but

do what you think”, by not being assertive and clear – I've really learnt on

the job to trust what I want. It was quite hard to learn that, particularly in

the industry, when funding came with different working demands.

Nina Danino:

The films that you made in

the nineties, The Whirlpool (1997), Crystal Aquarium (1995), Cold Jazz (1993) were all produced with

funding from television.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, the first was The Pool (1991), a commission for

Channel 4’s Eleventh Hour experimental slot, funded by the Arts Council. It

came with the proviso that you worked with a production company and a small

crew.

Nina Danino:

How did you find that

experience after having made your work yourself?

Jayne Parker:

Difficult but also very

valuable. I worked with the cinematographer Patrick Duval and that worked very

well. He took great care filming. I worked on several films with the

cinematographer Belinda Parsons. She's very sensitive as a cinematographer, and

we had a very good relationship, we worked well together. I think one of the

problems for me is that it made me lose confidence about using the camera for a

while. I could decide what was going in the shots, set the frame, and then

somebody else would check the exposure and press the button. I felt it more

keenly with the music films. Belinda filmed several of them but with the later

ones I returned to filming myself. That gave me back something that I felt I'd

lost - a connection with the moment of filming.

Nina Danino:

I agree, Sarah Pucill, Anna Thew and Barbara Meter have also

spoken about the importance or difference of filming and of looking through the

camera oneself.

Jayne Parker:

I think for all of us, there

is the effect of funding, often you can see it in the resulting film –

commissions can take you on a certain route. It can affect the look of the

film. Funding opens up the possibility to do things you couldn’t do on your own

but it comes with its own demands and production values, which is something

that I always wanted to resist.

Nina Danino:

Commissioning editors from

television and from the BFI had editorial control whereas the Arts Council

Artists’ Film and Video was more artist-centred funding. Maya Deren does warn

‘against the complications that would arise from an effort to emulate the industry’.[18]

I had to make a shorter version of “Now I

am yours” (1992) which was funded by Channel 4 because of broadcast time

slots.

Jayne Parker:

During that period I learnt

that funding is amazing because it allows you to do things that you might not

be able to achieve on your own, but it doesn't give you any more time. For

instance, for Crystal Aquarium, we

were able to film in Channel 4's studio and construct a scaffold to hold a

block of ice. It was an amazing stage setting that would have been impossible

to do on my own and yet we still had to be out by what, five or six o'clock.

You have this extraordinary set, but you have even less time than if you had

set it up in your front room or somewhere.

It's just a different way of

thinking and working. If I didn't know what to do at that moment, I had to

learn to take myself away and think about it and not transfer my own anxiety

onto other people because they didn't know what I wanted. They were just doing

their job, waiting for me to direct. But I should say that I don’t think I ever

feel out of control during filmmaking, as the outcome is my responsibility.

Nina Danino:

All your films still come

across as very controlled, precise and very highly crafted. Could you talk

about how you achieved this?

Jayne Parker:

I worked as an assistant

film editor, which was very useful and good training – in fact you got me that

job at the BBC when it had its own in-house training for directors.

Nina Danino:

There were a few of us from

the LFMC there. It could be frustrating if you wanted to be an experimental

filmmaker. I worked mainly on documentaries for the BBC and independent films.

I was totally committed to a path in experimental film and felt very conflicted

about those two sides but now I am glad I went through that training and

professional experience.

Jayne Parker:

Directors and producers were

making short training films and we assisted the editors. I didn't know how to

sync rushes when I went in on the first day. I remember Marek Budinsky showing

me how to do it. I feel very grateful for that insight into the industry.

Nina Danino:

Nicky Hamlyn, Marek Budinsky

were other artists at the BBC from the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC]. I was

fascinated to see how there are ways to shoot different kinds of films. The

Directors’ Training Programme which I worked on also did music and dance films

and short dramas.

Jayne Parker:

I liked the role, I liked

learning from them. I always like to be behind the scenes, being in the wings

of the theatre or being in the rehearsal room or being in the edit room,

they're the places of making.

Nina Danino:

It was interesting because

it showed the method. I'm fascinated by method. To learn how to organise a

cutting room or how to shoot for music or dance or point of view in drama.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, and a way to do it. You

know, even if it's small things like using a red pen to mark up the tins

containing sound, and a blue pen for those containing the image. That way you

can see at a glance what material is in the tin.

Nina Danino:

Yes, in documentaries where

there were often many hours of footage, it was imperative not to start editing

the ‘rushes’ – the footage developed by the labs – till you were properly set

up which meant having transcripts for the interviews and all the footage

logged. All these methods placed an order on the material. It was gruelling to

do. I never so much as cut one single frame of my films without logging

everything meticulously. This means that I can find everything on paper from a

description of that shot without having to search for it, to look for it

physically. No editing that I have done would be possible without the training

I did. Even a film such as Stabat Mater

or “Now I am yours” that are very

experimental and seem freely put together, every shot is logged and the whole

film constructed on paper.

Jayne Parker:

I also log every shot – it’s

necessary to keep track of the footage and know the limit of your negative. It

is also a way to get to know the material, to see its potential and let go of

pre-formed ideas or disappointment. It was very useful learning about editing

and filmmaking procedures. When I edit my films I am using an established

editing language.

Nina Danino:

Can you talk about using

this language in your films. You don't use the cutaway. This shot was the

standard method with which you could bridge jumps in the continuity of eye line

in drama or cover the jumps in an interview in sections of a documentary. This

jump is often smoothed over or left exposed today because the cutaway looks too

contrived. But these were professional techniques designed to hide the edits.

Also, it is somewhat violent to jump cut between shots of the person being

filmed, which is why it is often used as jolts in experimental film. Do you use

establishing shots which are a wide shot of the scene?

Jayne Parker:

I sometimes use establishing

shots but more often I shoot them and don't use them. I'm often filming

parallel actions and inter-cutting back and forth, so continuity continues

between shots as well as in the action itself.

Nina Danino:

You do use it in the

continuity form?

Jayne Parker:

Yes. I follow it, I'm using

the language.

Nina Danino:

But you're also disrupting

the language. Because you're not using all of the grammar, you're only using

some of the grammar. Could you talk about your use of the grammar.

Jayne Parker:

Yes. I remember someone

saying to me, it's usual to put the close up after the wide shot and I'd done

it the opposite way round. I didn’t like being told how to do, because the edit

was the way I wanted it to be.

Nina Danino:

Yes, I was taught that you

put the wide shot or establishing shot first and then the others. I worked

often with a very good editor called Colin Hobson. He would make changes on the

fly on the Steenbeck if we had the commissioning editors or the director in the

cutting room and they wanted to see an alternative cut and he did it in a

flash. I don’t like the point of view system and especially filming the over

the shoulder shot. I do like continuity as it is a way of giving a space to the

subjects filmed.

Jayne Parker:

For a long time, in my

films, there were never two people in a frame. Scenes were shot separately and

people brought together through the edit. I didn't have that crossing the line

problem when filming, although I might encounter it later when editing. Everything

is implied.

Nina Danino:

Can you talk about the music

films Thinking Twice (1997), the Foxfire Eins series (2000), Stationary Music (2005), Catalogue of Birds: Book 3 (2006), and Trilogy – Kettles Yard (2008)? They are pristine and shot immaculately in

terms of continuity and music.

Jayne Parker:

With those films, I have to

follow the linearity of the music. I am locked into it.

Nina Danino:

Do the performers play the

piece multiple times and you shoot it from different angles?

Jayne Parker:

Yes. For all the music films

I prepared detailed shooting plans, working out in advance the framing of each

shot and where in the music it began and ended. I would also film a master

shot, sometimes two, of the complete composition. Repeatedly playing some of

these pieces could be very tiring and I tried to minimise the number of times

the musician had to play. I only ever used one camera.

Nina Danino:

These are live and very intense performances. Do you take up a role as a director regarding the performance and also directing the performer musician?[19]

Jayne Parker:

I think with those films,

with filming people generally and with the musicians, I never want to take away

from the integrity of the performance, if it's ice skating or swimming or

musical performance. I wouldn’t tell them how to perform but it would be clear

in advance what they were going to do.

Still from Jayne Parker, Natalia Gorbenko in Crystal Aquarium (1995).

Copyright Jayne Parker. Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

Crystal Aquarium is also so precisely shot.

It has four performers: a drummer, a swimmer, an ice-skater and you.[20]

This film was awarded the Grand Prize and other accolades at Oberhausen in

1997. The music films have the same quality of precision, economy and

intensity. You never forget that there is a camera and framing and editing, but

the performer is able to perform. How do you combine the two?

Jayne Parker:

I always want to leave space

for them to be the musician or the performer. As I mentioned earlier with the

music films I follow the linearity of the music, its continuity. Some sections

of other films are shot with continuity in mind too, for instance the first

part of K. as I wanted to follow the

action through to the completion of the knitting. I think there is a different

approach when I’m not filming a musician or continuous action.

Nina Danino:

Could you say in what way is

it different?

Still of Michelle Drees in

Jayne Parker, Crystal Aquarium

(1995).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Jayne Parker:

Maybe it is slightly different in that the pace of the film is

determined by the editing and not driven by the tempo of the music. In the

diving section of K. I cut in-between

the action when the frame is cleared. I cut when there's nobody in the frame,

before I enter the frame and after I leave the frame – shots aren’t intercut.

This was a conscious decision. I've always liked the work of filmmaker Yasujirō

Ozu and it is a technique he uses. For example, if Ozu is filming a

conversation, we see an image of the first person, they speak, he then cuts to

the second person and they answer, then he cuts back to the view of the first

person, they speak and so on. The dialogue isn’t overlaid while someone reacts

to it. Also, I like his placement of the camera at the level of whatever he is

filming – I like to be in front of the subject I’m filming.

Still of Natalia Gorbenko in

Jayne Parker, Crystal Aquarium

(1995).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

The formal decisions and

spatial continuity also allow space for the performer which I like to give as I

mentioned earlier.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, I am very interested in

space, and I’m particularly interested in touch – and the action of touch, for

instance, the feel of the cold eel held next to the skin in The Pool, feeling the underside of the

ice in Crystal Aquarium, the act of

the musician playing a musical instrument, which determines the expression of

music. I think there is something absolute about material knowing through

sensation, through the hand. Also, with the music films, particularly because

music in itself has no obvious visible material quality, other than vibration

and the site of playing, you can film anywhere in the room and the sound would

be continuous in that space.

Nina Danino:

Does structural film inform

the formal precision, especially in the music films?

Jayne Parker:

I’m not sure it does in a

direct or conscious way. I definitely like a locked-off camera, the image

framed so the action happens in front of it. When I made Cold Jazz (1993), I realised I'd become so formal there was nowhere

to go, and that was difficult. This difficulty crossed over with the subject

matter of the film too. In that film there is no transformation, and the desire

for transformation is something that drives all of the early films. I felt

really stuck, nothing happens in the film, it's just consuming in the hope that

something will happen. In the film I open and eat a lot of oysters. I don’t

enjoy eating oysters – there is no pleasure. When you open an oyster you

destroy it. It's probably the most violent of all those films, because there's

a real death. For me, it is an image of consuming the most wanted thing, and

the act of consuming destroys it.

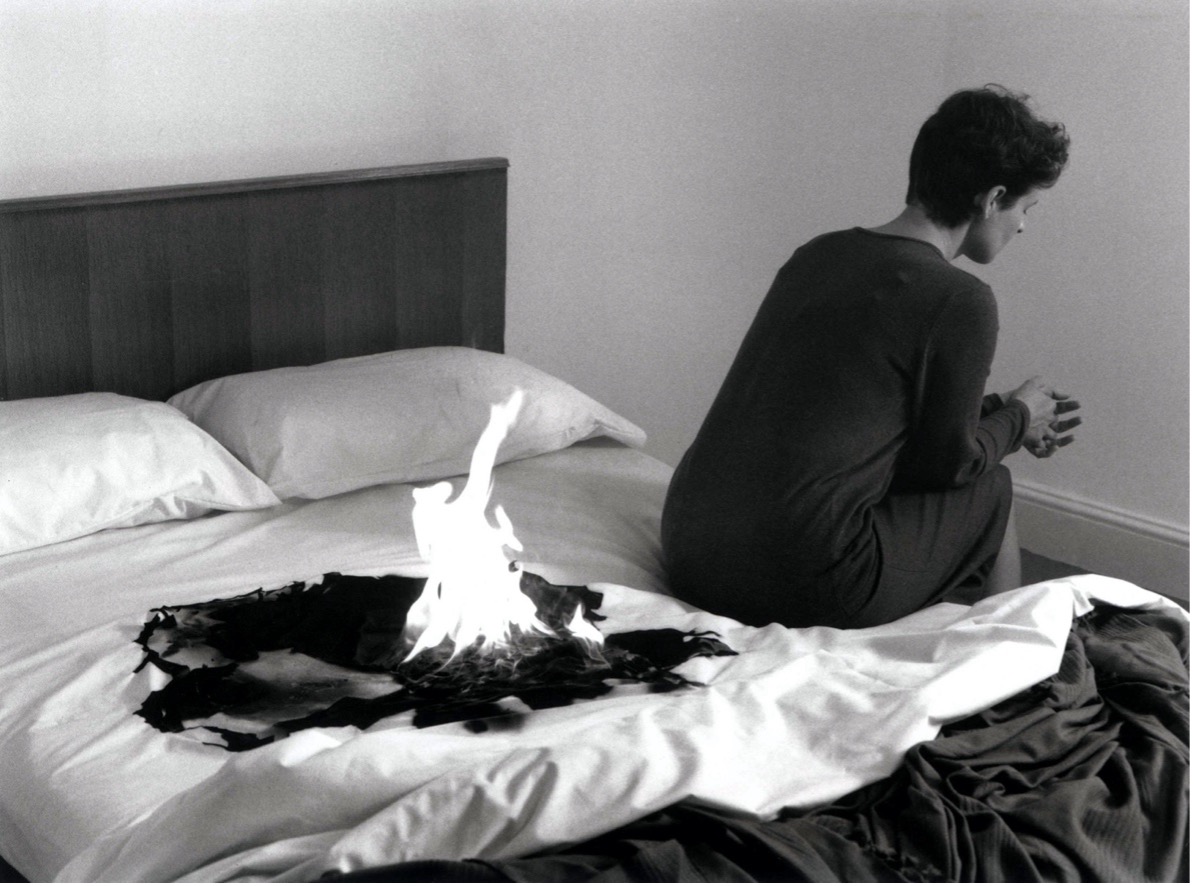

Nina Danino:

Was it the formalism or the

symbolism in Cold Jazz, the oysters,

and in Crystal Aquarium, fire, that

became something dead to you?

Jayne Parker:

The images are highly active

but their meaning within the film is one of arrest. With Cold Jazz it was the formalism within my approach that felt like

entrapment but then this was the subject matter of the film. There was no space

for spontaneity. I didn’t feel like this when I was making Crystal Aquarium.

Nina Danino:

You are the protagonist.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, I'm in both Cold Jazz and Crystal Aquarium, which I feel marked the end of me taking a

protagonist’s role in my films, although I appear briefly in Blues in B-flat (part of Foxfire Eins) (2000) and The Oblique (2018).

Nina Danino:

From 2000 onwards, you are

not so present in the work as a performer then? Did you begin to use other

performers again? Why did you decide to minimise your presence?

Jayne Parker:

First of all, I think of my

films as a form of documentation of performance on film. There is a strong

documenting aspect to how I film things. I’m directing the viewer to what I

want them to see through the editing, but also in the way the shots are framed,

and where the feeling is in what I'm filming. With Crystal Aquarium I felt I reached the end of what I could actually

embody as a performer. I'm not an actress, and that was my limit.

Production still from Jayne

Parker, Crystal Aquarium (1995).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

I wonder also whether,

because these are intense practices and you are at the centre of the work,

whether you wanted to be free of that role of protagonist and of being the

subject – under the camera lens and the gaze?

Jayne Parker:

I wanted to make work that

was less introspective, and the move to placing the musician as the focus

offered a way out of that. I felt I was repeating myself. But in the end, even

with the music films, there's the same subject, there's the body in relation to

object, object as body, inside, outside. Maybe it's not as obvious, but it's

exactly the same scenario really as in the other films.

Nina Danino:

Can you talk about making

these films and introspection?

Jayne Parker:

It was certainly a way of

looking at and confronting things that I found difficult. I've always made a

big distinction between my work and my life. What’s on the screen is not an

analysis of me. I move on, I change, I might think something different tomorrow.

Although it's a bit of a contradiction as I can't really separate out life and

making, as I’m filming things that resonate with me. I think of myself as a

gleaner, looking for images that carry or resonate in a particular way. I used

to think of the early films as beacons or holding structures, and when I saw

them they would reactivate what I felt, but contain it too.

Nina Danino:

Do you think that you were able to realise or confront yourself to some extent through the making of the films? Through a particular visual language of filmmaking?[21]

Jayne Parker:

It's a form of expression.

It's certainly a way of looking at and exploring things – trying to see things

as they are. I've always felt that the filmic space was completely free, and

even though my life might be moderated or moulded by society, or a situation,

or personal traits, no-one can tell me what to do on the screen. It is a

completely free space.

Nina Danino:

Are they a confrontation

with /of the self. Did you make them primarily for yourself?

Jayne Parker:

I made them out of a

compulsion to make them, and that drive that we talked about earlier, and

because it was a way of structuring, understanding and reflecting on the way I

see the world, the agency of the body, relationships, longing, restriction,

resistance, and so on. It is a way of ordering things.

Nina Danino:

Yes I see them as

confrontations with the/a self through visual language. Experimental film is

thought of as a free self-expressive form but at the same time we've been

describing it as a highly structured form. As a form of expression, it gives a

framework around which you can make a film which is not a limitation but a

structure. So, it's not just about unconsidered expression, it's a rigorous

visual language.

Jayne Parker:

Yes and also the

understanding of material – of 16mm film material. Just thinking of it purely

materially, for instance, the way you have to plan if you want to have

something superimposed or you want a dissolve – although I've never been able

to find a reason to do either of those two things, despite trying. The material

will only allow you to do certain things. If you haven't got the negative, you

haven't got the negative. I really like that necessary rigour.

Nina Danino:

It was so important that the

chosen visual techniques were intrinsic to what you are trying to say rather

than as a special effect or something which you could lay on top without having

a reason.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, it's the same with the

optical printer which allows you to reframe and repeat an image or repeat

frames in order to slow down the motion, or still the image. I love that

machine but then I think why would I reframe something? I should have framed it

like that in the first place. Why would I step print something? I should have

filmed it like that. This is my own inner voice, which won't allow me to alter

those things that I should have thought about at the shooting stage. I can see

other people do it and I like it, but I can’t do it myself.

Nina Danino:

The framing is so important

in your films.

Jayne Parker:

Yes. I like film’s

precision, that it can only be this frame. I always found that very difficult

when video first came in, that there were more possibilities with the material,

that there could be multiple edits and endings – for me there weren’t. There was

only the one I chose.

Nina Danino:

With video you can copy over

multiple times, whereas experimental film emphasised the present of making, the

means, the medium, the material – perhaps the photographic original. The

mechanics of film; camera, printers, editing machines, the engagement with the

means of production came from a structural approach but your films add the

symbolist and dramatic language. As well as Pierre Attala, your mentor at

Canterbury, were other teachers, thinkers, theorists important?

Jayne Parker:

There were teachers I had at

art school that were very valuable to me. On foundation in Mansfield Trevor

Ellis was a great supporter and early influence as was the artist Brian Catling

at Canterbury, who told me that I was dying in painting and got me to move to

sculpture. Chris Welsby and Lis Rhodes at the Slade were important figures and

introduced me to the world of experimental and avant-garde film in London.

Still of Claire Winter in

Jayne Parker, Freeshow (1979).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

A.L. Rees was an important

figure and a good friend. If I showed a finished film to Al, he would never say

very much, but he would indicate his reaction with a characteristic nod and a

pause. I always thought ‘if Al likes it, it's all right’. Yes, he was a very

important figure. The critic Michael O’Pray too, and the journalist-critic Jill

McGreal. I would like to mention Maya Vision and in particular Christopher

Collins, who over-saw the production of many of the funded films.

Nina Danino:

What about the feminist

debates, did you engage with those at the time?

Jayne Parker:

I've always considered

myself a feminist. When I was young, I was particularly aware of women's work

and feminist debates. I never wanted anyone to tell me what to do. I think I

thought that I could avoid being subjected to patriarchy!

Nina Danino:

Did you engage with feminism

as a context for your films?

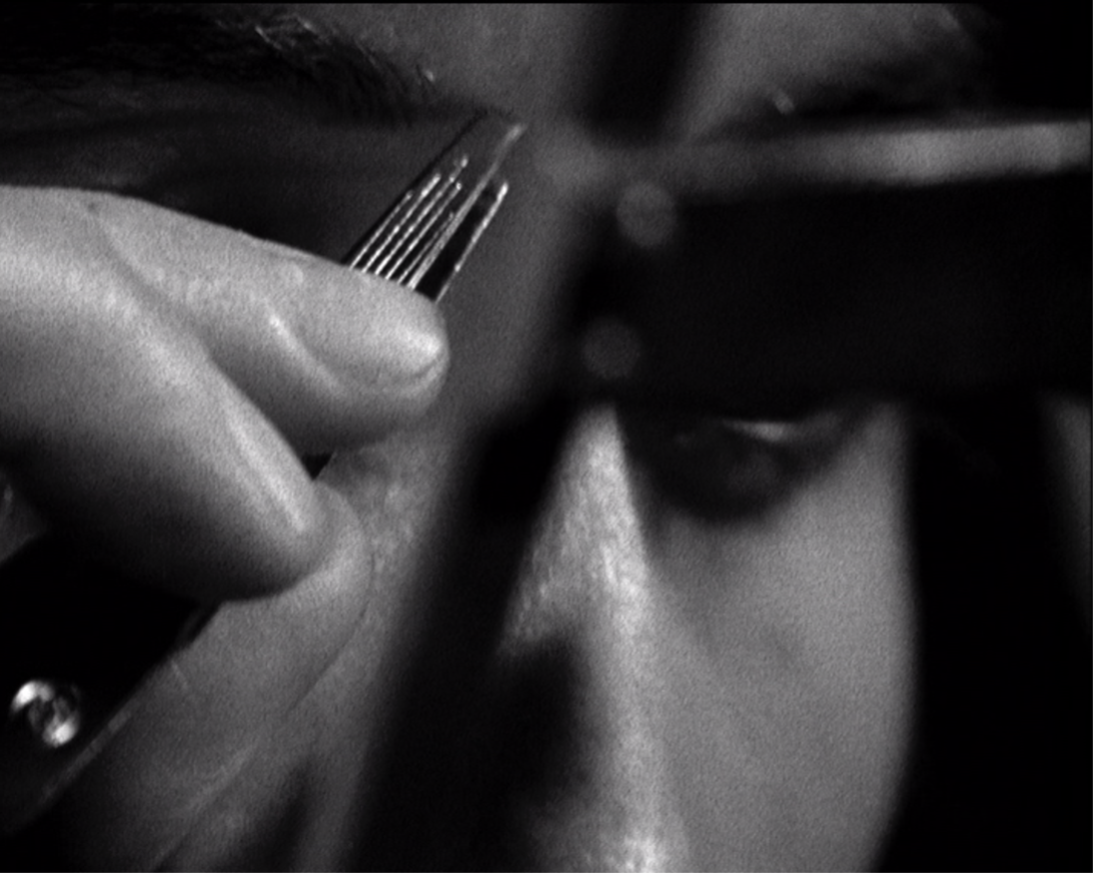

Jayne Parker:

Yes but in an oblique way.

In a film like Free Show (1979), it

is more direct. Free Show looks at

where violence starts, and it can be in the domestic, in the smallest action in

the home or in personal bodily attention such as the violence of plucking

eyebrows.

Nina Danino:

Yes, the films could be read

from a feminist perspective. Certain acts refer to domestic chores which seem

to be performed against their purpose as an act of resistance, like the ironing

in Freeshow, which is burning a hole.

The protagonists are female and play out restrictive social conditions, the

re-staging of domestic chores is performed in a restrained way: the cutting,

the chopping, the recipes, highlighting the violent gestures.

Jayne Parker:

That film, through its title

‘Free Show’, references performing

without the giving of oneself, as a form of resistance. Everything is done with

a sense of withholding, and maybe resentment.

Nina Danino:

The obsessive plucking of

eyebrows is painful to watch because in big close up it shows the pull of the

skin. The sheets in Snig are hung to

dry in the normal way but when spread out are full of nightmares emblemised by

eels squirming and then the dead eels which are shaken out.

Nina Danino:

I Dish, which is a signature narrative experimental film of yours I feel,

stages the gestures of the two protagonists, a man and a woman, who are never

seen together but perform different ritualistic activities in what’s implied as

the same space. The woman is seen in a somnambulist-like act of solitary

eating. Then the man is seen washing himself also alone – the images are

unexpected and dissonant. The lack of sound further isolates the protagonists

from each other in the domestic space.

Still of Claire Winter in

Jayne Parker, Freeshow (1979).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Jayne Parker:

I had this idea that men

could wash and be cleansed but women couldn’t be cleansed in the same way.

Nina Danino:

The films are less read or

written about from that perspective. Yet they are feminist in the sense of

depicting female protagonists’ resistance and gesture.

Jayne Parker:

It’s interesting. When the

films were first distributed I went to Circles,

which was a women’s film and video distribution organisation. I felt at the

time it was a way of having control over how my work was seen. It was good to

be part of Circles.

There was a lot of work

being made by women about women and health, social issues and agendas, and I

began to see that as soon as you put one of my films alongside these films it

was out of place. Also, I made Snig

and they didn't want to distribute it over concerns that it was too violent,

and although I understood the reasons for their decision, I felt silenced. At

least this is how I remember it. It was probably 1982 or 1983, and there was a

lot of discussion about how women should film women, how you mustn't fragment

the body, and awareness of how images and signifiers could be read as

patriarchal, for instance filming a women behind a desk may be seen as a

patriarchal symbol. It came out of a need to challenge accepted ways of filming

that perpetuated patriarchal view points and values. Women were challenging and

changing the way they were portrayed and their place in the industry. But, in

my youth, I felt I didn't want women to tell me how to do something – I never

want anyone to tell me what to do.

Still from Jayne Parker, Snig (1982).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

Nina Danino:

There were a lot of rules

and messages.

Jayne Parker:

Yes, there was Cinema of Women, Circles and the LFMC. I had a great respect for the people in all

of these different organisations and for what they were working to achieve. Film can be such a useful tool for

raising social issues and consciousness. I moved to the LFMC when I felt out of

place, when I felt I wasn’t

addressing things in a way that fully reflected the values of Circles.

Nina Danino:

Circles distributed historical and feminist films by woman. Cinema of Women had a more social,

political activist, educational and social agenda and the London Film-makers’

Co-op centred on artists’ filmmaking. There was a perceived choice as to where

you distributed your films as Sarah Pucill also talks about in our conversation.

Jayne Parker:

It is interesting to

remember the times and reflect on the history and the endeavour to take

control.

Nina Danino:

What was your experience

when moving image started to shift into the gallery in the nineties? Did it

shift your artistic identity also? In the eighties and nineties, we called

ourselves filmmakers, I don’t recall anyone being called an artist filmmaker. Being

an artist was a given but no one used the term artist. Expanded cinema was part

of experimental film it was not called installation then but I don’t recall

galleries showing film before the mid-nineties. I may be wrong. In the eighties

if you were an experimental filmmaker it was in the context of a cinema-culture

in which you showed in programmes, festivals, film tours and cinema screenings.

Jayne Parker:

It was an interesting time.

I always felt divided as an artist and a filmmaker. My films didn’t naturally

find a way into the gallery. There were some artists or filmmakers,

video-makers, who made the transition into the gallery. But I don't think I've

ever been seen as a gallery artist.

Nina Danino:

Did you want to be?

Jayne Parker:

In some ways yes – I wanted

my work to be seen – and maybe more now, but in other ways I found it

problematic seeing films within the gallery context, and still do. When you can

come in to the film at any point it makes a nonsense of the decisions you make

when editing, when you don't want to reveal what's happening until later in the

film. Creating meaning in film through editing is cumulative, what we see, what

we think we see, and the pacing of it directs the meaning.

Nina Danino:

Do you want to show your

work mainly in galleries now?

Jayne Parker:

I’m mainly showing in film

festivals and film screenings but I am very happy to show in a gallery if

anyone asks me. But I think it's changed something. I used to love going to

film screenings and afterwards thinking about what I saw. What did I see? Did I

see that? How you remember or mis-remember things, how sometimes you can see

someone's work and elide two films together, and then when you see it again you

think, I can't remember it being like that. It's like a new experience each

time. In a gallery a looped work is playing all the time, and I think we’re not

prepared to engage with duration in the same way, at least I don’t find it easy

to settle into the pace of extended moving image work in a gallery.

Nina Danino:

Yes giving the time to the

screening and one’s full attention till the end of the film.

Jayne Parker:

Yes and to actually give

oneself to that work. One wonderful screening I attended in the 1980s – I don't

remember where – was of US filmmaker Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954). It was projected in a

pitch black theatre, screened in darkness. It was so rich. The experience has

stayed with me all these years.

Nina Danino:

In the gallery, sound is

difficult to control. Also, as a viewer it is grey light and you are aware of

the other people around you.

Jayne Parker:

It's almost like you're one

removed from it, rather than being lost in the space of the film. The black

isn’t black, now almost everything is digitalised. In a cinema setting it's an

experience, a collective experience. It's one of the things that made me – and

this is more in relation to performance art really […] – turn towards experimental music. I found in

experimental music the live experience, when a lot of performance work had

become mediated through video. There's something about being present in the

moment of projection or performance that I value. That is where the experience

is – in the moment.

Nina Danino:

Yet you said you want to

engage more sculpturally with the physical space. And you're making sculptural

pieces using magnolia wood and stone carving? You were also talking about

expanding out from the intensity of linear experimental film.

I still want intensity and I still want to make films – that

hasn’t changed. When I was a student at the Slade, I was in an area called

Experimental Media, and we were based in what is now called the North West

Wing, in white cubical spaces. I hadn't realised how important being in a

sculptural environment had been for me as an undergraduate student, and I

missed the materiality around me. I think from that moment on, object making

seemed to fall away, and filmmaking drew everything in. I was never able to mine

the strata of my ideas, or make different variations through other means,

either in photography or through object making. Now I can see how I could have

done that, and how I can do that now. A turning point was the work commissioned

by Spacex Gallery and Film and Video Umbrella, a series of films with Anton

Lukoszevieze, called Foxfire Eins (2000).

They were commissioned for and installed in gallery settings. It made me

realise that I could make work that could occupy space. It’s the same with

making objects. It's about extending out into the material world.

Nina Danino:

Which perhaps is a

reconnection with your sculptural formation.

Jayne Parker:

To the physical world, yes.

Nina Danino:

As well as showing the film The Oblique in the exhibition Still Life together with photographs at

A.P.T. Gallery (London) which we mentioned at the start of this conversation

you are also showing hand sized stone sculptures and branches.

Jayne Parker:

Yes – it was a joint

exhibition with painter Lisa Milroy. That was a big thing for me because it was

the first time I'd shown predominantly sculptural works and photographs, as

well as film, in a very long time.

Nina Danino:

So it is a new phase of

making?

Jayne Parker:

Yes.

Nina Danino:

Would you like to make any

concluding remarks or is there anything that you would like to comment on from

this conversation before ending?

Jayne Parker:

Only that I really value

this chance to speak with you in such detail. Our conversation feels like a

receptacle for common ground, shared history, experience, materiality and

process. I’ve thought about things I haven’t thought about for a long time. Thank

you.

Nina Danino:

Thank you too.

Still from Jayne Parker, Stationary Music (2005).

Copyright Jayne Parker.

Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London.

_____________________________________________________

Biographies

Jayne Parker was born

in Nottingham in 1957. She completed her foundation at Mansfield College of Art

(1977) before studying sculpture at Canterbury College of Art (1977–80) and

Experimental Media at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London

(1980–82). In her films objects, performance and gesture are brought together

to explore space, expression and the physical body. In 2008 a DVD compilation

of her films was released by the British Film Institute in their British

Artists' Film series. She participated in From

Reel to Real: Women, Feminism and the London Film-makers’ Co-operative (2016),