Part 2 (of 6)

Structural lyricism: Autobiography, memory, optical printer, indices, vision

Barbara Meter in conversation with Nina Danino (2020/24)

Artist Barbara Meter. Photo: Ewald Rettich (2020). Courtesy of Ewald Rettich.

_______________

This conversation is an edited transcript of an in-person conversation between artists Nina Danino and Barbara Meter conducted in Amsterdam in 2019.

________________

Barbara Meter has been closely involved with experimental film in the UK since completing a master's degree in video and film from the London School of Printing in 1995.[1] Since making her first short film in 1967 she has made experimental films, feature films and documentaries that have been widely screened internationally. One of the initiators of the Nederlandse Filmmakers Cooperatie (Dutch Film-makers Co-operative) along with filmmakers Mattijn Seip and Nico Paape – a branch of the Studio ter Ontwikkeling van Film and Filmmanifestaties[2] (STOFF) – she was a member over the short period during which it was active, between 1969 and 1973. Like other co-ops established in Europe in the 1960s and 1970s, this non-hierarchical organisation emphasised self-organisation and do-it-yourself approaches to filmmaking. It helped foster a coalition of makers based in the Netherlands through production and distribution, as well as the reception of international artists and makers, and screenings at the Electric Cinema in Amsterdam, an underground venue for experimental works run by makers from the co-op. Although short-lived, the Dutch Film Co-op had an influential impact on the cultural climate of Holland and the Electric Cinema helped establish the Netherlands as part of an international experimental circuit.

Barbara Meter programmed experimental films at The Electric Cinema between 1970 and 1972/3, and at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from 1972 until 1975. From 1970 she also lectured on experimental film – in universities, art colleges, youth centres and museums – and worked as a curator for the Shaffy Theater, the Malkweg and the Wilhelmina Gasthuis Theater in Amsterdam (until 1988). In 1988 she organised the Festival van de Moderne Film: Film Als Autonome Kunstvorm [Festival of Modern Film: Film as an Autonomous Artform] at the Stedelijk Museum, a two week programme showing experimental works by artists and filmmakers from all over Europe and the US.[3]

This conversation takes its main points from an article Barbara Meter wrote for Undercut, the magazine of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative (LFMC) in 1990. Titled ‘Across the Channel and 15 Years’ this was an account of the experimental film scene in Britain in the 1980s around the LFMC.[4] During the course of the conversation, each speaker refers to what Barbara Meter said about herself during correspondence and preparation for the conversations, which started in 2018. Nina Danino also refers to the critic P. Adams Sitney and ‘lyrical film’, making references to ‘structural’ film centres of practice, predominantly in New York and London.[5] They refer to its characteristics as a form of film practice in the UK associated with the filmmakers working in and around the LFMC in the 1970s. In this context, structural film centred around the use of the camera as the technological means to produce film experiments such as in the work of British artist Chris Welsby, foregrounding optics and techniques such as superimpositions of images and forms of re-printing. Central to some of these techniques were contact and optical printers. The LFMC got an optical printer in 1976, enabling frame by frame re-photographing of existing footage and effects such as copying, superimpositions, re-framing, re-printing from different sized film-stock formats (such as Super 8 (8mm) to 16mm), colouring through gels and filters, fades, reversals and other visual effects. Another exponent of structural film in the UK is artist Malcolm Le Grice.[6] Despite the different approaches adopted by varied makers in different countries, structural film largely emphasised the material of the medium itself, such as its grain, light, movement, often using mathematical structures and ordering logic.

The discussion also references the often anti-illusionistic stance of structuralism, through restriction of representation and narrative, as advocated in the writings of filmmaker and theorist Peter Gidal, who saw his approach to the structural as a means to counter the illusionist technologies of film as escapist entertainment for ideological purposes.[7]

________________

This conversation is one of a series of six discussions undertaken by the filmmaker Nina Danino in 2020. They were revisited and edited in 2024/2025 when they were published online.

Please note that the opinions and information published here are those of the speakers/authors and not of LUX or the wider research team and institutions involved with their funding, transcription and publication.

Published online by LUX, London (2025)

Editing and research: Claire M. Holdsworth (2020/2025)

________________

Conversation

Recorded 23 and 24 February 2020 (Amsterdam)

_____

Part 1

These conversations are about your films – about how you use film to delve into your thoughts and feelings, your personal experiences as a filmmaker. I really enjoyed seeing your work again. You've made a lot of experimental films and in this conversation we won't go into interpretations of individual works. Rather, I’d prefer to talk about your film language and the notion of inscription and materiality as well as the context in which you practised experimental film in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

You went to film school and attended the Netherlands Film Academy between 1961 and 1963. How did you come to filmmaking and why did you choose to work with film?

Barbara Meter:

I loved film. I remember one of my first film experiences, when I thought, “Oh you can say something with film which you can't say in another way”. It was a neo-realist film – I can’t remember the name or maker – an image of a fly in close up, walking over some dirty things for washing in a kitchen, walking on a dirty window. There wasn’t any language or any music with it – it was just a fly walking like that. I'd never seen anything like it. I remembered that image. Then, when somebody said, “there's a film academy starting” I thought, “well, there you can combine all the things that I like: literature and music, and visual arts.” That's how I came to attend the Netherlands Film Academy. It was a two year course where the technical department was separated from the scenario/directing section. I took directing, of course, so when I finished, I hadn’t operated a camera or used an editing table.

Nina Danino:

You've said that you started to make experimental film because you wanted the freedom it gave, from the fiction and documentary film that one would have learned at a film school.[8] You’ve also said that you became what you call ‘a convert’ to experimental film, after your visit to the London Film Festival in 1970, where you showed your film Familie Nasdalko aan zee (1968).

Barbara Meter:

That's right. Familie Nasdalko aan zee is a short narrative which was a little bit absurd, let's say, a bit hip. It wasn’t experimental at all. In the Netherlands they thought that because it was a little bit hip, that I was experimental. That's why the Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap – in English, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science – said, “Barbara is our representative at this experimental film festival, because she makes experimental films.” I didn't make experimental films, but I didn't know that.

Nina Danino:

What did you see at the London Film Festival that year? What was it that made you take up the camera and make films experimentally?

Barbara Meter:

I was flabbergasted by what I saw there. I thought, “What's happening?” At first, I didn't understand anything, but I was completely fascinated by the abstract imagery of it. Then, at some point, when I tried to understand it, I thought, “you shouldn't try to understand it, just let it work on you”. That's what I did. Then, I came to love it because I felt this freedom – that you don't have to have a narrative. You don't have to have a producer. Like Maya Deren (whom I didn't know about at that point) said something to the effect of you only needing a camera and your body and a brain, and that's it. That was for me, completely free – it gave me a freedom.

Nina Danino:

Were there particular films that struck you?

Barbara Meter:

I think it must have been Berlin Horse (1970). That impressed me. I think I saw Schneemann's Fuses (1967) and some abstract films, like Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970). They impressed me because I thought they had more to do with visual art, real art, than everything I'd learned in film school, which was much more bourgeois. That was also an issue. I felt that the atmosphere at the London Film Festival at that time and all the experimental filmmakers whom I started to meet then, was much closer to me. They lived and felt like I did, like I stood in front of the world, let's say. I felt at home with the films, with the people. They were politically engaged. They loved the same things as I did, so I made a lot of friends.

Nina Danino:

Who did you meet?

Barbara Meter:

I met a lot of people – artists like Malcolm Le Grice, Steve Dwoskin, Paul Sharits, Mike Leggett, Mike Dunford, Sally Potter, Peter Gidal, and programmer David Curtis. I discovered that Peter Gidal knew my uncle from Frankfurt, which is very strange, you know – because that was my past. I'd never met anybody who'd met my family, because they were spread out or had died in the Second World War.

I was so inflamed with all that after I went back to Amsterdam, where I was living together with the filmmaker Mattijn Seip. He didn't go with me to the London Film Festival, but when I came back, I sort of infected him with the whole thing. He became very interested in it and he immediately also started filmmaking. He made Double Shutter (1972) which even then was quite radical. He was also very rebellious: he didn't have a form for it but he found it in experimental film. He felt at home in a different form to the more traditional filmmaking that we learned at the Film Academy, where we met. Together with the filmmaker Nico Paape and later Jos Schoffelen and Lynne Tillman, we wanted to establish an organisation in which you didn't have to submit a script to get a commission, where people would judge if you would get money or not. We needed some equipment, a camera, a printer; some sound recorders. Mattijn and Nico applied for a subsidy from the Cultural Ministry in 1970, and they got it. We established a kind of work-place because we had a space, a room that we could rent, and the equipment, the projectors.

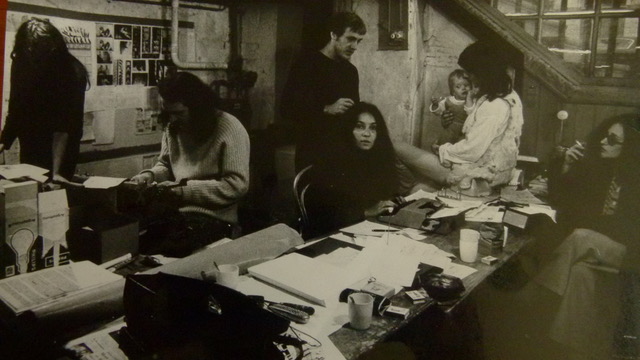

Photo of the Dutch Film Coop, Amsterdam (1970/71). Left to right:

(standing) Jos Schoffelen; (sitting) Albin Thoms; (sitting) Barbara Meter;

(standing) Mattijn Seip; (sitting on table) Niko Paape (with the daughter of

Anneclaar Muller); (sitting with cigarette) Lynn Tillman.

Photographer:

Anneclaar Muller.

We had money. We also wanted to programme experimental films and established the screenings at the Electric Cinema in 1970. Jos Schoffelen and Lynne had a slot in a cinema in Amsterdam where they showed all kinds of films, also experimental and they called that Electric Cinema. We took over that name. The Australian filmmaker Albie Thoms helped us set up in the beginning. Malcolm Le Grice also helped to install an optical printer the next year.

That was just a fantastic time, for two years, at least. Mattijn and myself (and sometimes others) programmed films.[9] Most of the time, I was the programmer at Electric Cinema. For both the Electric Cinema and later at the Stedelijk Museum, I organised a film touring circuit all over Holland where the same films were shown and filmmakers visited Utrecht, Groningen, Nijmegen and other places, also to youth clubs and Museums. The Stedelijk Museum screenings went on for two years till 1975 after the Electric Cinema stopped in 1972/3 once a month. STOFF stopped when the Electric Cinema stopped in 1972/3. The screenings in the Stedelijk Museum, plus the circuit it (and the Electric Cinema) established, were important too: filmmakers were doing performances in a museum. Malcolm Le Grice performed, and another artist from England, Annabel Nicolson performed her Reel Time performance there in around 1975.

Nina Danino:

STOFF then, was the umbrella organisation for experimental film and theatre; the Electric Cinema then was the venue that you took over for screenings; and the Dutch Film Co-op was a space like the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC] with a membership where you had equipment for filmmaking and also was active in the years 1970 to 1973.

Barbara Meter:

Everything came together at that point, when Albie Thoms was with us. I have a nice photo that illustrates that time –one of the most fantastic times of my life. Each week we had filmmakers coming, the British artists Mike Dunford and Sally Potter amongst many others. Mattijn and I had a very small flat with an attic, so people stayed up there.

Nina Danino:

Song for Four Hands (1970) is a dual portrait of you and another person filming each other. It has a greenish hue and there are superimpositions. The sound is a drone which is taken from one chord of a Mahler symphony. It is in-camera edited and the method is playful, the subjects are smiling and reacting to each other and to the camera.

Barbara Meter:

In Song for Four Hands myself and Jos Schoffelen gave the camera to each other. Jos was another filmmaker who was part of the Electric Cinema and the wider Studio ter Ontwikkeling van Film and Filmmanifestaties (STOFF). He's actually not made films for 30 years, but at the time he was very radical and a fan of Malcolm Le Grice’s work and other forms of structural film.

Contact

scan of Barbara Meter, Song for Four

Hands (1970).

Copyright

Barbara Meter. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

Your next film Portraits 1971-1972 (1972) is an intense display of many experimental techniques in the visuals; flickering, superimpositions, fast editing, it has filters or gels which colour the film in red and blue colours amongst others shot in home interiors, at tables, reading newspapers, by windows. It features the faces of the friends in mainly close ups, smiling, reacting to the camera and one man, perhaps the host, ignoring it. You can’t get to know these people, they are only quick impressions, they are subjects of the camera and the shooting.

The main subject is the aesthetic created through the technique. Sometimes the frame is split into four and different faces flash on and off and it is all held together rhythmically. There are lots of processes, which intensify the visual and optical impact of the film. There is re-filming off the wall. Projection of identical films which after a short time get out of sync and the rhythm changes. While the visuals change, the soundtrack remains the same throughout, it is a piece by the minimalist composer Steve Reich, an exponent of modernist avant-garde. All this is highly controlled, but the rhetoric is of improvisation, it looks free and enjoyable to make and feels like an immediate experience.

Barbara Meter:

That re-filming was the first time I did it my work. I didn't know about the optical printer, which photographs images, but I was already doing it by projecting the film and re-filming off the wall in Portraits you know.

Nina Danino:

In your first experimental film From the Exterior (1970), the camera is on the outside on the street and looks at people inside their homes but in the next films Song for Four Hands (1970) and Portraits 1971-1972 (1972), which includes your partner Mattijn Seip and other friends, the camera is amongst the people and you as a filmmaker as well.

Barbara Meter:

At that time the filmmakers Sally Potter and Mike Dunford were living together and staying with us (as I mentioned before). I made a portrait of them and other filmmakers and friends who came.

Nina Danino:

Filming itself is at the heart of it as well as creating a social network between filmmakers. It is experimental film which enables this approach. And this also connected up with filmmakers from the London scene?

Barbara Meter:

It did absolutely, I went to London often because at that time there was so little experimental film or filmmakers here, except for Frans Zwartjes. I came into contact with him before I went to London in the seventies. He was one of the first experimental filmmakers, I think, in Holland. He made his own films, he did his own camera, his own sound which I had never thought could be possible. He developed his own material, very stark black and white and very expressive, experimental, a little bit absurdist films.

The first films I saw, I liked very much, the rest of his work is not very interesting for me. Frans Zwantjes was also chosen to go to the London Film Festival the same year that I went. He had real experimental films and I didn't. I was impressed with the psychological way he thought. They were about human relationships, power, sexuality, cruelty and they had an absurdist approach which was not like mine but still influential for me. He was friendly with the filmmaker Stephen Dwoskin, who was based in London, with whom he had some things in common. Frans was a bit older. He's died now. Despite Frans’ work, there was no experimental context in Amsterdam: we were the first to establish regular, experimental film screenings through the Electric Cinema.

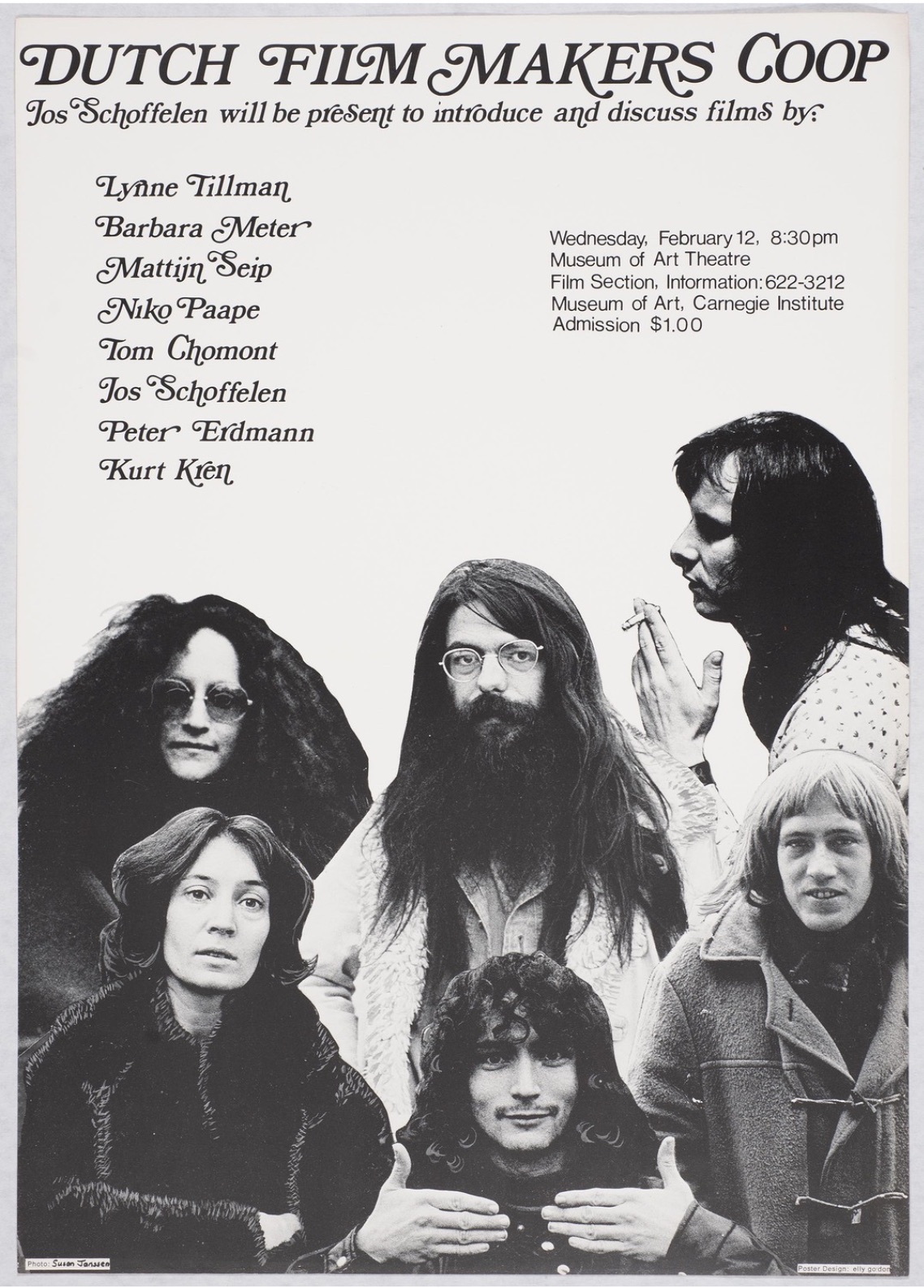

Poster

for screenings by filmmakers of the Dutch Film makers Co-op, presented by Niko

Paape and Lynn Tilmann, Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute (12 February 1975).

Artists pictured: Top (left to right) Lynne Tillman, Jos Schoffelen, Niko

Paape. Bottom (left to right) Barbara Meter, Tom Chomont, Mattijn Seip.

Source: Carnegie Museum of Art Archives (2020).

Nina Danino:

You’ve mentioned Dutch filmmakers and Sally Potter and Mike Dunford, perhaps you could say more about the other filmmakers who visited, to give a sense of how these connections were happening?

Barbara Meter:

Each week we had different filmmakers visiting including Carolee Schneemann, Annabel Nicolson, William Raban, Wilhelm and Birgit Hein, Gill Eatherley, Kurt Kren, Paul Sharits, Tom Chomont, Valie Export, Alfredo Leonardi and others and we made contact with each other. I was influenced by the screenings and it was very exciting and very nice. It was just heaven. [Laughs]. It was great.

Nina Danino:

Your experience of the experimental film context in London and Holland that you are describing puts across how for artists, experimental film created energy and excitement. The practice of filmmaking also created social connections with other artists too, as can be understood in the making of Portraits 1971-1972.

Barbara Meter:

I have never thought of those connections in that way. Portraits has sections within the frame with Mike and Sally on either side. I was so impressed with the people around me and I wanted to make a cubistic portrait of them. I danced with the 8mm camera (it's all filmed on 8mm).

Nina Danino:

You were filming the people around you and yourself.

Barbara Meter:

I'm not so often in front of the camera, except in Song for Four Hands.

Nina Danino:

Your film Traces (1991)[10] was shown as part of the same London Film Festival programme as was my film Stabat Mater (1990)[11] at the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC] in 1990.[12] What stayed in my mind after seeing Traces were the images of you, which are slowed down and coloured.

Barbara Meter:

In Traces I do represent myself, but I have rejected that film. And I never show it.

Nina Danino:

This is a trace-like portrait of you but you're saying, “No, I prefer to be behind the camera”.

Barbara Meter:

That's right.

Nina Danino:

Your films have been described as or associated with a form of ‘lyrical structuralism’. Can you talk about this?[13]

Barbara Meter:

Yes, it's the term that Jos Schoffelen – the man in Song for Four Hands, who was my lover at that time – said of me. I thought – lyricism and structuralism? How can they be together? But at the same time I thought there is something to that, maybe in the difference between them, which is true about my films and structural film. I think that I just liked to be as anti-illusionistic as I could. I actually agree with structural film and not mythologising the filmmaking. So, I did incorporate that notion into my films.

Nina Danino:

The American film critic and writer P. Adams Sitney talks about lyrical film[14] and Stan Brakhage’s film The Wonder Ring (1955).[15]

Barbara Meter:

I didn't have the films consciously in my mind, but it is very possible that the films of Brakhage have influenced me.

Nina Danino:

Sitney discusses that the screen is filled with movement and the look of the camera, that movement is very much part of a lyrical reverberation. The lyrical poem as a form inscribes the feelings and emotions of the poet. Brakhage’s film and yours perhaps both are centred on the presence of the camera and the awareness of the person looking through the lens of the camera. The slight movement of the handheld camera looking is part of this rhetoric. In Penelope (1995), the light is moving and casting mobile reflections. The editing is also interrupted with flashes of colour which also relays a restlessness. The motility of the grain and particles thus creates the idea of movement which creates a sense of aliveness all the while also inscribing a reflective approach.

Departure on Arrival (1998) refers to trains and the passage of time and places. Sitney also talks about the lyrical style in the repetition of shots, the continual flow of movement and images of movement such as trains, distortions, reflections, patches of light and so forth, so all that describes the visual language of this film.[16]

Barbara Meter:

Well, that's everything that I use, yes. I just wanted to move, not always but most of the time, I think.

Nina Danino:

In the outline discussion for this conversation you said that you wanted to go into “your attempts to delve into the romantic thoughts and feelings belonging to my personal experiences”. [17] Do you see yourself as a romantic filmmaker? Can you say more about this?

Barbara Meter:

I think it's more in the subject matter that I wanted to reflect on, especially love affairs: on what you go through as a woman but also what you go through in love. (2005) is completely about that. A Touch (2008) is about my relationship with the English filmmaker Guy Sherwin, but it's also about saying goodbye to somebody.

I was sad at that moment, so I think

that for me – even if that was contradictory to structural film – I wanted to

express my feelings and that is very romantic, I think. My feelings and

thoughts sometimes are undistinguishable, in a way.

Nina Danino:

So did film offer a means and form for responding to your circumstances and expressing your emotions and feelings?

Barbara Meter:

Yes. The atmosphere in which you live and in which you go through things. I tried to spontaneously recapture that atmosphere when I was sad or when I was in love or when I was saying goodbye to somebody, or when I just was observing something which I saw on the street like in my film Andante ma non troppo (1988). I don't know if you remember it, that's made out of this window here.

Still

from Barbara Meter, A Touch (2008).

Copyright

Barbara Meter. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

I recognised the street outside, it’s a corner of your street.

Barbara Meter:

It's about women waiting on the street and women caring for their children.

Nina Danino:

You've referenced female archetypes, the character of Penelope who is the ever patient figure who waits for the return of her husband in Homer’s epic poem.

Barbara Meter:

Penelope(1995) is about waiting, which I experienced, which I still experience and I hate. How do you describe the waiting that you do for a man to take initiative? Although I did take initiatives when I wanted to be with someone, I noticed that emotionally I was waiting often […] for a man to be as devoted as I was. It is not that I was passive in practice, but rather psychologically […] except when I was with Mattijn Seip who was as committed as I was.

Nina Danino:

In my first film First Memory (1980) I wanted to represent this feeling of passive waiting through the pace of the film and waiting as a female condition of ‘femaleness’ – these terms were in flux.[18]

Barbara Meter:

Penelope very much was about women sitting at home. Although I didn't do that myself. I was a feminist and I saw that women were bound to a house and waiting for the men to come home to take the initiative and make the decisions.

Stills from Barbara Meter, Penelope (1995).

Copyright Barbara Meter. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

Ariadne refers to the original Greek myth. Ariadne – a young girl helps Theseus slay the Minotaur through her clever strategy of the thread which helps him out of the labyrinth but soon enough he abandons her. In the Faust legend, the innocent young girl Gretchen is also abandoned in one of the stories, like Penelope she becomes an eternal feminine. To the German author Goethe, who wrote one of the best-known versions of the myth, this figure was one of ‘pure’ contemplation.[19]

The film conveys the disquiet associated with abandonment. This is heard in Schubert’s music and the act of spinning. The shots of the sea, cliffs and mountain landscapes especially at the end evoke the Romantic grandeur and at the same time there are sections of a blurry female figure at the loom which seems to refer to craft and the work of the hands, women’s work. The shadows that the loom casts on the wall echoes the shape of film spools – and film projection or editing through the intermediary of sewing which references other film works within experimental film on this topic, such as Annabel Nicolson’s Reel Time, which was originally shown in London in 1973 before also being shown at the Stedelijk, as you mentioned before. The sewing/weaving metaphor is there in the foot pedalling and of course the hands. There is also the presence of Super 8 in the material and texture. So there is a lot of beauty in how all this is done. It seems to combine a grand ungraspable feeling referenced through the music with a homebound personal evocation.

Barbara Meter:

That is a very personal film, yes. I was brought up in the German culture, and my mother and I read from Goethe's Faust and Gretchen, the lover of Faust, is waiting for him. She falls in love with him and is disquieted, she is weaving all the time. Weaving is also within Greek literature, the Greek myth of Ariadne and her weaving. I thought of that as an image of women. They're busy doing things like weaving but they're waiting. I loved that myth, the imagery and also the music by composer Franz Schubert, of the famous poem about Faust, the beautiful piece Gretchen am Spinnrade [Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel] (1814).

Nina Danino:

There is music in many of your films.

Barbara Meter:

Music has often been my guide actually. It's like breathing.

Nina Danino:

Your soundtracks are very evocative. How do you like to use music to enhance an atmosphere?

Barbara Meter:

You have to be so careful with music in film because it is often used as a kind of illustration of a mood or even a mood.

Nina Danino:

Is creating a mood the same thing as atmosphere?

Barbara Meter:

I don't like the way that traditional films dictate your moods through the music.

Nina Danino:

It can tell us how to interpret and sometimes even be emotionally manipulative.

Barbara Meter:

I hate that.

Nina Danino:

Structural film often used the mechanical sounds themselves and structural/materialist film resisted the use of sound, many experimental films are silent. From a structural background you were always supposed to resist sound and music other than as an objective material or as part of the process or as keeping out cultural associations or questioning or confronting them.

Barbara Meter:

We did, except the very first film I made which was called Norwegian Wood (1967) from the title of a song by The Beatles [Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown), 1965]. There I was throwing it all in. It's a kind of experimental film in a way. I didn't know I was doing that, but I associated the lyrics with all kinds of imagery. I didn't do my own filming at that point.

Still from Barbara Meter, Ariadne (2004).

Nina Danino:

Verschijningen / Appearances (2000) is made from black and white photographs, did you want to evoke a particular feeling of a time and place – mittel Europa? Departure on Arrival (1996) is evocative of different Europes. The Europe of your films as Nick Collins writes is German and Eastern, rather than French or Mediterranean.[20]

Barbara Meter:

Appearances evokes Germany from before the Second World War. At least that is what I wanted.

You can see it in the landscapes, the statues, hear the music. It also refers to an older Germany through Bach etc. It is the Germany mainly of my grandparents and my parents when they were young. The film is made of photographs which I found left by my mother, all of which were taken before I was born.

Nina Danino:

The sound also references German culture to Goethe and his Faust –in the lieder song.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, it was quite important.

Nina Danino:

The images from Penelope seem loosely and freely shot, spontaneous. Did you find it liberating to use the hand held camera?

Barbara Meter:

Absolutely, it became a kind of extension of yourself.

Nina Danino:

Was it shot on a 16mm camera? That’s quite heavy.

Barbara Meter:

I had a 16mm Beaulieu camera without sound.[21] It wasn't light, but I didn't mind that actually because I trained myself to use it.

Nina Danino:

They look as if you're filming on Super 8 because they look so lightly shot and fluid.

Barbara Meter:

Some films like Ariadne were actually made on 8mm and then enlarged. Song for Four Hands(1970) was made on 8mm, edited in-camera and enlarged in the optical printer.

Nina Danino:

The use of light and dark, fading an image to the point where sometimes it disappears but sometimes other images receive light and reappear and this makes them fluctuate and pulsate through the opening and closing of the aperture of the camera. Is this the predominant method to filming the photographs used in Stretto (2005)?

Barbara Meter:

I loved doing that, yes. It's mainly the films made on the optical printer, like Departure on Arrival (1996) and Appearances. That is what the optical printer can do. In those films, for me that was very important for the feeling of time. I don't know if you get that feeling when you look at the film but for me it expressed that feeling. That time is just going in and out and you're running after it, you can't grab it.

Nina Danino:

Do you still have your own optical printer?

Barbara Meter:

I did. I don't have it anymore because I can't see through it.

Nina Danino:

Would you describe what it does?

Barbara Meter:

It refilms what you have already filmed. The optical printer is made out of a camera and a projector. You put the image that you want to refilm into the projector. The projector is lit from behind and you sit in front of that and you can manipulate the film with the device of a little electric button. Moving it frame-by-frame you can refilm it. It means that you can alter the light. You can alter the framing. You can come close, very, very close and so close that you can see the grain and then you can withdraw again or not. You can fade it in, you can fade it out. You can do all kinds of things with it, which is manipulating it to the utmost, but I think it shows the way that you look at the materiality of film.

You can manipulate the light. Therefore, in Appearances for instance, the photos are of people who have died. I thought, “I want to make them a little bit alive.” Not really but you know, I tried to make them have a more three-dimensional quality. I thought about it and I first made a slide of the photographs.

Nina Danino:

It gives it that translucency, so, they're not flat grained.

Barbara Meter:

Exactly. Then, I projected the slide on a little frame that Guy Sherwin made for me which had a grainy layer that you see through. Then when it was projected, I walked a little bit with the camera alongside it, so that the light moved. Because of the light, the film looks as if the person is moving. I actually loved working like that. Playing with light and making life through light.

Nina Danino:

When you blow up an image or you re-film it, there's a point where it begins to lose its relationship to the original source.

Barbara Meter:

That's what I loved about it, also.

Nina Danino:

There's also a struggle to see and a lack of clarity sometimes, the focus fluctuates from shot to shot as previously described in Stretto (2005). It seems to be taking vision to its limits.

Barbara Meter:

It does.

Nina Danino:

Is that a metaphor or something that you wanted to make us think about as physical in the work?

Barbara Meter:

It's not a metaphor, I don't think so. But let me think […].

Nina Danino:

I mean it's an aspect of the way you've filmed it […].

Barbara Meter:

Yes, for sure, but I also like it very much because it goes from the real image into the materiality of film and of the photograph. Then you can see the grain of the photograph and the grain of the film.

Nina Danino:

It's a kind of flux of both.

Barbara Meter:

Exactly and it sort of draws it out of reality. Of course, a photograph already is not reality, but I wanted to emphasise that part. Also, speaking about Romanticism, I thought it was very poetic, when something comes from real imagery it becomes more misty and mysterious maybe. That’s what I really liked about it, plus as I say, the materiality of the filmmaking comes through.

Nina Danino:

It goes through a number of operations, which presumably allows you to kind of get quite close to this material and to know it very well and to see what you want to take from it. It's a very intense process of transformation through re-photographing from its original source.

Barbara Meter:

It is. It was very intense and I loved doing that. I just couldn’t do that anymore, I don't know. Maybe, probably, as it is my eyes doing it.

Still

from Barbara Meter, Verschijningen /

Appearances (2000).

Copyright

Barbara Meter. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

How is your eyesight?

Barbara Meter:

It's very bad. I have macular degeneration, and it’s not getting any better. Degeneration is never getting any better. It's going very slowly. I notice it because when I sat in the cinema for instance, like five years ago, I still could read the subtitles; I can't anymore. I can never go to a Spanish film because I can't understand it. I have to see them on the computer if I can see them at all.

Nina Danino:

So, the physicality of vision is very central?

Barbara Meter:

It is, yes.

Nina Danino:

In a way, vision is also like a struggle.

Barbara Meter:

It is now, yes.

Nina Danino:

But also, in the films, it seems you're always grappling with how to see and wanting to grasp through the eye.

Barbara Meter:

That's true. But then, when I made Appearances in 2000, my eyesight wasn't as bad as it is now, but it has never been good of course. I've been short-sighted since I was a small child.

Nina Danino:

So, vision is a way of representing […]?

Barbara Meter:

Reality.

Nina Danino:

We have to get through your vision to get to how you see reality. It's through a physical engagement with a camera lens.

Barbara Meter:

That's true and the optical printer and the optical sensor, yes. And the light.

Nina Danino:

Even though vision is not a metaphor.

Barbara Meter:

It's not, no.

Nina Danino:

I understand the resistance to metaphor. It is the act of seeing, where vision and how we see is what is at stake or a kind of looking through which one engages with the medium, the material and the optical mechanism.

Barbara Meter:

The material is very important, yes.

Nina Danino:

It is also a physical engagement with the limits of one's own bodily vision and the optical mechanics?

Barbara Meter:

It is also a psychological engagement. Especially in Appearances, because all the people are dead. They have an image, but that doesn't mean that they're there at all.

Nina Danino:

Even though the world of the films is quite nebulous and difficult to grasp, the light and shadows become part of the struggle to get to clarity […].

Barbara Meter:

That's also in my thought, the struggle to bring clarity.

Nina Danino:

It’s a struggle but it’s a creative struggle. In Appearances the vision is making images appear like ghosts, to come in and out of focus, but they are […].

Barbara Meter:

Not quite there.

Nina Danino:

The rhetoric of vision of the films is, as we’ve been saying, quite soft and fades in and out. The sound world of the films also fluctuates in and out. The music and sound lead you as it might a partially sighted person as a guide which leads you through it but it also suggests transience. In Appearances there is a quiet atmosphere of muffled voices, distant steps, radios. These are short quiet bursts.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, it's about an impression.

Nina Danino:

I wondered whether that was your structural inheritance coming up. The idea that we mustn't give too much pleasure.

Barbara Meter:

[Laughs] Yes, it's possible.

Nina Danino:

Pleasure was very much something that had to be measured and resisted.

Barbara Meter:

I don’t know. I didn't do that consciously anyway, but I think I used those snippets of sound of impressions. Not the whole thing, because it shouldn't be an illustration. It was something in itself but it wasn't quite there and it's still about grasping reality which I think is very difficult for me [laughs] and I think there's a sense – not in all my films – here there is a sense of grasping or not being able to grasp reality. I can't grasp it especially not in Appearances, that is true. These are no concrete sounds about which you can say, “Oh that's that”. It's just an impression and it goes away like everything goes. Another theme in my work, I think, is time.

Nina Danino:

It's ephemeral and maybe that is also what creates a sense of loss.

Barbara Meter:

Well, I was just thinking of that today because as a Jewish child, I was in hiding.

Nina Danino:

You sometimes hinted at this.

Barbara Meter:

Yes. I think this anxiety of things being taken away and making everything unsure; you're not sure if the world like it is now, will exist tomorrow. That's what I think I have expressed, that kind of feeling through what you say about the snippets of sound. It's images which go out and in of the light and in and out of focus.

Nina Danino:

Within your grasp but they leave you as well.

Barbara Meter:

They leave me. Time leaves you and everything is sort of ephemeral in my thoughts. Yes. In my reality.

Nina Danino:

Did you feel that as a woman filmmaker representing yourself in the visual language of the films that we are discussing, that they are representing a subject of a sort of slippage where you can’t grasp or represent a totalised self?

Barbara Meter:

I think so, as far as I can tell.

Nina Danino:

The female subject position of slippage could be critiqued for being essentialist – the woman as not being able to keep a grip, yet it is a woman producing the images in a discourse of the woman as film author. Sitney says that the ‘Romantic’ artist portrays themselves as reading books.[22] Your films draw from literature and the European music classical tradition. Therefore it creates a self-portrayal as cultured.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, that's because of my education. Though I don't want to present myself as such consciously – it's because my mother was a music teacher and I was brought up with classical music.

Nina Danino:

You've got a piano here.

Barbara Meter:

I love to play […].

Nina Danino:

Do you still play?

Barbara Meter:

Not anymore, but I did for a long time.

Nina Danino:

Could you talk about what music means to you?

Barbara Meter:

If I were to be born again, I would become a musician I think, if I could. It's what gives me focus. I notice now that when I'm in a mood that is not very nice or I don't feel very well psychologically or about something, when I put on music it gets me back to myself. It makes me whole again sometimes, not completely whole, but it's an essential part of my life. I couldn't really live without it.

Nina Danino:

The range of music in the films is wide from the thirteenth-century hymn Stabat Mater, music sung by Italian soprano Cecilia Bartoli, or the contralto Katherine Ferrier, pieces by composer Johann Sebastian Bach and Italian opera to the minimalist music of composer and artist John Cage. I think that's really what the content is.

Barbara Meter:

It's true. It's in my head.

Nina Danino:

The sounds of Departure on Arrival conjure so many places and invoke many sensations of an acoustic and aesthetic world. Appearances has black and white, muted colours, flicker, it's got fades, it's also got superimpositions. The aperture, opening, enlarging, reframing, grain, dust, handheld re-filming.

These are all pleasurable aesthetics and you talked about the pleasure that you get from your hands-on use of the 16mm film gauge as a medium, and the way that you enjoyed working with it. Can you talk about how you created your image?

Barbara Meter:

You mean altering the image in a personal way?

Nina Danino:

Yes, your work on the optical printer.

Barbara Meter:

Well, can I talk about it in a specific way […]?

Nina Danino:

What did the optical printer enable you to do to develop a visual language?

Barbara Meter:

In Departure on Arrival what I wanted to do – and that's why it's called that – is […] I had this feeling, because I got a bit older and started to think that life is sort of a cliché […]. Then suddenly, it’s today, you can't grasp the time. You can't, it's just happening to you. You are passive, you can't do anything about it. You can't structure it, you can't. In your life you can't […]. That's the kind of feeling, of the fleetingness of time, that I wanted to give a form in Departure on Arrival. That is why there are so many fade-outs and fades-ins, and it just flows all the time. There's never any, let's say, statement in it, and that is why I used those techniques.

Nina Danino:

You’ve talked about grain and how you don't mind the dust?

Barbara Meter:

No.

Nina Danino:

These are not effects, they have a physical materiality.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, in a sense. What I don't like about, let's say, traditional film is that life is presented as perfect and all shiny.

Still

from Barbara Meter, Departure on Arrival

(1996).

Copyright

Barbara Meter. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

Yes, digital definition, like 4K or 8K screen pixels is hyper sharp and flat.

Barbara Meter:

Digital techniques go further and further into that direction. For me, it's getting farther and further away from my inner life: from what I experience as life to me or something like that. Also, the dirt that the film gathers in the optical printer. You know, your life is not perfect, nobody's life is perfect, as it is projected. Maybe not in the stories, but in the digital imagery it's too hard, too perfect for me to enjoy, actually.

Nina Danino:

When I was working on Stabat Mater on the optical printer with the filmmaker Nick Collins it was the struggle against dust that slowed us down. We didn't want any dust. We had to clean the gate every few frames, in the end there was not one speck but this was counterintuitive because it was a dust laden environment and in an experimental approach you would use that as part of the film. However, I was glad to get the pristine blue sky.

Barbara Meter:

Sometimes you don't want dust of course.

Nina Danino:

It was the colour saturation and the London Film Co-op was not dust free!

Barbara Meter:

It was Nick Collins who taught me to work with the optical printer.

Nina Danino:

Well now, you are known as being a master in the use of the optical printer.[23]

Barbara Meter:

I don't think I am [laughs].

Nina Danino:

There’s an aspect of virtuosity in experimental film. There is an aspect of technical display when you take what the technology or mechanism can do, to its limits. Is there a gendered difference in the approach to this? When the male artists do it, it is seen as part of their ability but maybe sometimes if women do it […].

Barbara Meter:

See what I can do?

Nina Danino:

Of course, there's an element of showing off. There were the feminist critiques of the implied mastery. Yet I find it very exhilarating to see something crafted to a very high degree of skill almost as a performance. But I do also wonder whether that is something that is perceived differently in women, to men.

Barbara Meter:

There probably is, actually.

Nina Danino:

The English structural film movement and the canon of artists working with structural film was about the mastery of visual techniques. The use of multiple superimpositions or repetitions was important for films such as Berlin Horse (1970) mentioned earlier or ‘tour de force’ films such as Room Film (1973) by Peter Gidal. David Larcher’s analogue work embodies an intense relationship with the printers, which he knew how to manipulate with skill. That high level of technical display could also be considered intimidating and perhaps there is an element of being highly competitive too. I know that you are considered to be a master of the optical printer.

Barbara Meter:

Not anymore.

Nina Danino:

But your films come out of that mastery of the equipment, of the optical printer. On this question of women and mastery. Do you consider a particular film of yours a ‘tour de force’ – that displays a very high level of skill?

Barbara Meter:

Well, this is not a direct answer to your question, but I must say I was very proud that I could master the optical printer. I was really amazed because I'm a very a-technical person. At the Netherlands Film Academy, I was in the ‘scenario’ division. There was a technical part, which were only men who were Directors, and the scenario part, the women were in there and some men as well.

When I left the Netherland Film Academy in 1963, I had never touched a camera. I had never touched montage, or a Steenbeck machine.[24] I'd never touched real material film. I'd only thought about it. As a result, at first, I was quite awkward. I thought, “I can never handle a camera. It's impossible”. I was completely afraid of it too. Then at some point – also because of Frans Zwartjes who did his own camera and developing, which I also loved – I thought, “well, maybe I can. Maybe it's not too difficult” and I found that it wasn't that difficult. Then, with the optical printer it was a bit more difficult, and of course Nick Collins was a great teacher – I thought, “I'm a woman and I can do this.”

Nina Danino:

Maybe it's from that angle that we have to understand it but your experience sort of confirms that perhaps women filmmakers did not have a sense of being their own masters and yet you are.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, I remember I was really proud of it.

Nina Danino:

Do have a particular way you like to edit? Do you edit mostly in-camera?

Barbara Meter:

Let me see […]. There

are some films of course like Song for

Four Hands and

Nina Danino:

It's very difficult to edit 8mm, the frames are too small. On 16mm, do you edit on the Steenbeck or do you digitise it now?

Barbara Meter:

Yes, now I digitise it and edit that way.

Part 2

Nina Danino:

Can we talk about the context to your work, perhaps your roles as a film programmer and curator as well as artist?

Barbara Meter:

When we talk about experimental film, my involvement started in 1970 after attending the London Film Festival. As we said, after programming at the Electric Cinema, I went on to programme for the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, where again lots of filmmakers showed their work – mainly the same as had also shown in the Electric Cinema. Stedelijk Museum also went on for two years, but not every week, once a month.

Nina Danino:

You mention your involvement with experimental film starting in 1970 after going to the London Film Festival. You were programming and you were making experimental films. Did you have a sense of yourself as a woman in that film context of the seventies?

Barbara Meter:

Not really but that is the funny thing, because I remember that when I saw these structural films, which impressed me very much – I thought “I could never do that.” [Laughs].

They looked technical, but also they looked sort of mathematical. That was not my way of thinking, but I admired it. They were logical and thought out and I am working much more intuitively, which is probably a feminine difference, I don't know.

Nina Danino:

In my experience, it wasn’t that women were marginalised at the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC], not at all, but that the subjective was not considered to be rigorous theoretically or intellectually equal to objective filmmaking. It was particularly dismissed by some second generation structural male filmmakers.

But going to your generation of the seventies, in the article ‘Across the Channel and 15 Years’ (1990), you say that you consider that women were making equally fine mathematically structured films too.[25]

Barbara Meter:

Some of the female makers working at the London Film Co-op [LFMC] were, like the artist Gill Eatherley. I didn't see many of the filmmaker Lis Rhodes’ films, so I don't know about her. I really like her films Dresden Dynamo (1971) and Light Music (1975-1977), but I didn't see them at that time. As we mentioned earlier, what impressed me was Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses (1965) because it was technically very well done but it was the poetry of it which impressed me, together with it being sexually explicit. Of course, Stan Brakhage also made personal films. I don't make the distinction between the personal in the experimental films of the women and the men. Later, I saw films by another younger American Filmmaker, who documented his children and his home. Anyway, there were several men, including Guy Sherwin, who were putting themselves into the films in a personal way, so it's not only women.

Nina Danino:

Film could be a form of consciousness itself or the structural reading would be that it is a representation of consciousness.

Barbara Meter:

I made my first experimental film, From the Exterior (1970) and Peter Gidal wrote a review in Time Out about it, it referred to my being a woman filmmaker.[26] I wasn't as conscious of myself as a woman filmmaker.

My feminist consciousness let's say, came much later. Then I thought, "I don't know very many women experimental filmmakers except the ones that I had already met and talked about", but this was an awakening. It made me aware of something that I wasn't aware of before.

Nina Danino:

Yes, it could be a moment of realisation. You've mentioned how consciousness was so central to the idea of women becoming aware of themselves as women […].

Barbara Meter:

Also, I remember that I was friends with the writer Lynne Tillman at that time, who also was involved in the Electric Cinema. I heard her say, “this is male chauvinism” and I'd never heard the term. In Holland we weren't there yet […] well, it was just beginning, I think. That was the other thing that happened to me at that London Film Festival, I became much more aware of the fact that I'm a woman, even a woman filmmaker and what my position actually would be in terms of being a woman.

Nina Danino:

There were other areas of practice which equally saw themselves as radical in the stories they told and the issues they highlighted. How did you engage with the emergent feminist or women's narrative cinema of the seventies and eighties in Holland?

Barbara Meter:

I wasn’t involved much with narrative film at the time and I engaged with the women's movement some years later.[27]

Nina Danino:

Feminist filmmaking came out of the women’s movement as one form of protest and analysis and different perspectives. Marleen Gorris from Holland made A Question of Silence (1981), a feminist revenge fantasy. It was supposed to be polemical but the film language was arguably conventional but with a feminist message.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, I was quite critical of that film. I wasn’t involved much with narrative film as I’ve said but I did see it of course. I didn't like the answer of violence with violence. I'm a bit pacifistic I'm afraid. I know it ended with the women beating the man with coat hangers, that was the last image of the film. That is what I didn't like about it, because I thought it wasn't an adequate response. It was more angry than it was thoughtful, but it made an impression and of course, in a sense, she was right.

Nina Danino:

After having made experimental films, you decided to turn more to political documentary? In ‘Across the Channel and 15 Years’, you said that you asked yourself whether experimental film could have answers to the political debates of the time –‘I was tangled up in at the time as to whether experimental film was ‘politically relevant’ or not, (to which my answer then was no)’.[28] Not just the position of women in film, but also around social issues – and you got involved in more political filmmaking.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, after I had left the Dutch Film Co-op and wasn’t programming anymore for the Stedelijk Museum either around 1974, I became involved with POLKIN which was a little group with Mattjin Seip, Rene Mendel and myself who become committed to making socially engaged films, a political cinema.[29] That also had to do with the fact that I was pregnant. I was thinking about which world my son or daughter would grow up in. I didn't know at that time, so I got engaged in teaching methods and then I got more awake towards the political situation in the world. My then husband Mattijn Seip became psychotic – he had episodes – and when he came out of them, he would tell me about his treatment. We talked about it and we got involved in the anti-psychiatric movement which was happening then. We made a little film together about that. I also got involved in a kind of movement which was very left wing and wanted to change the whole way of teaching.

Nina Danino:

Who were the films for?

Barbara Meter:

We showed them all over the place, in schools and other institutions. There were at that time, lots of youth centres, because the focus was much more on youth. This had to do with the hippy movement and the whole resurgence of youth being important, and the music which came with it.

Nina Danino:

In conversations in London, you never spoke about your documentaries and narrative films, they seemed to be in a separate part of your practice to your experimental film. And you referred to them as separate.

Barbara Meter:

That's what it was actually, and also in my thoughts because I couldn't find a way. I tried in the political films to find a way between experimental films and documentary, but I didn't succeed. I couldn't find the way in which I could be original enough to say what I wanted to say, to have content in the documentaries.

Nina Danino:

How have you found a way? Up to the Sky and Much More (2015) – for your father– is called an experimental documentary, and Loutron (2009) you also call a documentary.

Barbara Meter:

More of a poetic documentary.

Nina Danino:

So, do you feel now you have found a way of combining these approaches?

Barbara Meter:

Yes, I’d say that's changed because it's coming together more now.

Nina Danino:

Talking about conversations in London, we first met at a screening at Guy Sherwin’s in London in the late eighties or early nineties.

Barbara Meter:

That's right. I met Guy Sherwin in 1991, I think, something like that. I don't know exactly why I was in London at that time. Maybe I was just visiting or something? Annabel Nicolson was there, and I think the artist Nicky Hamlyn, as well as Nick Collins who we mentioned.

Nina Danino:

Yes, it was to keep artists’ film culture going through film screenings where you could bring your work to screen on the 16mm projector and discuss each other’s work which was so much a part of the experimental film context that we discussed earlier but was coming to an end by this time. The London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC] was still there but it wasn't strong anymore.

Barbara Meter:

Yes. I had also enrolled in the London College of Printing. I did an MA and I really enjoyed the thesis, where I compared the way that found footage is used in experimental film and in narrative films.

Nina Danino:

Now we're coming to the end. When we first discussed doing this conversation one of the things you wanted to talk about is your struggles that you have been going through and film. I wondered whether film relieved you of those burdens and struggles not just by enabling a revisiting of the past and your family which must have been a source of comfort but also literally for example, in Convalescing (2003), where making film is a kind of companion.

Barbara Meter:

Absolutely, I was convalescing and as Guy was at work usually during the day, I was alone in this little room and as I got better, I wanted to make something about it.

There was this blue ‘luxaflex’ blind and I was very enclosed. So, it was an expression of a personal experience in one moment of time. It was very comforting, I must say, and I also didn't feel so passive anymore and that is where 8mm is so beautiful. Because the 8mm camera is easy to handle since it’s so light and that meant that it made me use it even when I was ill in bed.

Nina Danino:

Yes, your films to me feel quite calm and quietly observational, sometimes detached even in places.

Barbara Meter:

True, yes, it could be.

Nina Danino:

Perhaps yours do it in a quiet and melancholic way.

Barbara Meter:

Yes. I understand that now.

Nina Danino:

Has making films also enabled you to come to terms with loss or perhaps other absences?

Barbara Meter:

Well, I was just thinking about it recently, because I was interviewed recently for an upcoming film and I was confronted with my period in hiding, during the War.

Nina Danino:

You've mentioned your period of hiding before and I thought to myself, “I've never asked Barbara about her period in hiding. Why have I never asked her about that?” But I'm going to ask you now.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, well I'm going to tell you. [Laughs] I've been confronted with it now and it's very strange. I've realised that I've made a film about it.

Nina Danino:

What is the title of the film?

Barbara Meter:

It's called Distance to Nearby (1982).

I had completely closed off. I didn't allow any emotion to take hold of me, so – it was the whole period. The whole two year period I was in hiding was kind of closed off for me.

Nina Danino:

How old were you?

Barbara Meter:

I was three and a half – four till almost six, when I was there with that strange family.

Nina Danino:

Were you in a particular place hiding?

Barbara Meter:

Well, it wasn't actually hiding in the sense that I had to hide in an attic or something like that. I was taken to the province of Overijssel, to a small town called Kampen. I was told later that I had been taken there by the Resistance Movement. Of course, I wasn’t aware of it and the odd thing is that I don't remember saying goodbye to my father or my mother. My father was not living with us anymore, but I was very attached to him, but I can't remember, you know. I just completely blocked it out.

Nina Danino:

Well at that age you don’t have a concept of memory, do you? It becomes a trauma maybe?

Barbara Meter:

Sure, but when I was confronted with my hiding, recently, I told the woman who was interviewing me, that I could actually from my memory go through the interior of the house I stayed in. Then just some days ago, I was thinking about that actually and I did enter the house as I saw it in my memory. Suddenly, I realised how dreadfully alone I had been at that time. I never realised that, and I started crying. I've never cried. I didn’t at that time nor later, only now I'm 80 [laughs]. So strange. That made me realise that the house influenced me quite a lot. That whole period I did actually experience loss very much, it was more subconscious. You know, your feelings go in strange ways. They go in secret ways. I realised that I sometimes do things because of the loss. That is not a good way of doing things.

Nina Danino:

You mean in life, not in film?

Barbara Meter:

No, not in film. No, I mean in life. Falling in love with the wrong person or something like that, or going after something that you can’t have?

Distance to Nearby expressed what I have just told you. I had actually shut out the middle part, which is the hiding part, which is in black and white and doesn't move very much. Before and after there's more colour and movement.

Nina Danino:

But you were a small child at an impressionable age.

Barbara Meter:

I couldn't exactly trace how it affected me, but I know that I actually adapted to my environment at that time.

Nina Danino:

But you must have shown incredible resilience to be missing your parents and yet at the same time to adapt yourself to the conditions.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, well I didn't miss my parents. I didn't let myself miss my parents. I must say it like that. I realised what I told you now. But I didn't let it through. I never cried then but I adapted to the language as well. When I came back from hiding, I didn't speak any German or Dutch, I just spoke the dialect of Overijssel.

Nina Danino:

Appearances you said is dedicated to your mother and your father. You said you wanted to do something about your background and your family and to revisit it through photographs, and in Up to the Sky through your father’s letters to you as a child, which became quite a successful book.

Barbara Meter:

It was, yes. I think that has all to do with loss, because I don't have any family. I mean I didn't have any aunts, uncles, father, of course not. My father's parents were still alive when I came back from hiding. I saw them once and then they died too, but just from old age. My uncle I knew, because he was still alive after the war, but that was the only one. He lived in Germany, so I didn't see him often. I was one of the children that didn't have any family around me. I think that this whole sense of not having a context, except for my mother, which was a very problematic relationship between us, made me sort of want to recover this context later on in life.

Nina Danino:

Film as a photographic medium has the potential for this spectral or death-like aspect.

Barbara Meter:

Well, I wouldn't call it death, but I would call it time, maybe. For me that kind of film is very much to do with preserving time, because celluloid itself deteriorates in time and disappears from the surface, the emulsion just gets lost. The thing that I wanted to do with Appearances is make the dead alive again. I mean of course that's not possible.

Nina Danino:

They are ephemeral presences which recede and disappear, so they come alive in a way but for very short periods of time.

Barbara Meter:

Very short period, because of course they are not.

Nina Danino:

Alive.

Barbara Meter:

I also remember that maybe that idea came because I was invited to Frankfurt am Main which my mother’s family comes from. Her father was a very well-known doctor there. And he was honoured by the town of Frankfurt and as the only grandchild I was invited to go. Then I visited the grave of my grandmother, she's buried in the Jewish graveyard there. That is her [laughs – pointing to a framed portrait on the wall].

Nina Danino:

In white chalk and pencil isn't it? On a dark grey paper background. The portrait is quite fragile or ghost-like which fits in this conversation.

Barbara Meter:

Maybe it was a sketch. I don't know. I've never asked my mother, but I love it. I think it's beautiful.

Then I realised for the first time because my father doesn't have a grave, my mother doesn't have a grave now. Then I was confronted with the first grave in my life of someone of my family and then I think the idea came about for Appearances. That there were more people and that they really had lived. That's the thing, I realised that my grandmother had lived, before she was just an image or somebody about whom there were some anecdotes – but it was there and when I saw the grave it was much more. It came to me that she is really real.

Portrait

of Barbara Meter at her house in Amsterdam (2020).

Photo

by Ewald Rettich (2020). Courtesy of Ewald Rettich.

Nina Danino:

So, maybe film did present the photographs as a comfort of memory.

Barbara Meter:

It did.

Nina Danino:

Has making the film allowed you to regain access to those images and to the sense of having a family?

Barbara Meter:

Of having a family. I mean it was very ephemeral, of course, because they weren't there anymore. But still, I could feel more – maybe after the film Appearances I could feel that they were there. For once in a lifetime, they were there. They had lived and I was part of them.

Nina Danino:

Appearances and Departures on Arrival are they part of an impulse to leave a mark, to leave a trace?

Barbara Meter:

You always express what you have lived through. I think that even in a distant way, that is always what's happening. If I think of my films now, I can see almost in every film, not every film, but almost in every film I can see parts of myself returning all the time. Different parts but, yes, even From the Exterior (1970), for instance.

Nina Danino:

Your neighbourhood.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, wanting to be part of something that you can't quite get to. You know, looking at these families cosy, behind the windows and I look at them but I can't get through it.

Nina Danino:

You are filming outside but you're looking in through their windows.

Barbara Meter:

So that's very much it. I think it’s why I wanted to do that film – and that is a theme. The windows are a theme in my work which sometimes come back now in the new film. There will be windows again with lights behind them.

Nina Danino:

When I asked you about writing that I should read before our meeting you said, “Oh there's not much written on me anyway”. But your work has been getting shown recently.

Barbara Meter:

A bit more now than it was let's say ten years ago.

Nina Danino:

The work of the eighties and nineties has been restored.

Barbara Meter:

That's true, EYE Film Museum, Holland have restored all my experimental films.

Nina Danino:

The DVD – Pure Film (2008) – looks beautiful. You showed in Alchemy Film Festival and Monica Saviron toured a programme to New York to Wisconsin, seven or eight festivals and also spoke about them.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, this was a big factor in putting me into the light again. Curator Federico Rossin was one of the first actually, I think. I must have been in 2000: he took a whole programme of my films to Lussas Film Festival in France and he wrote about it in the catalogue.[30] It was exposure of my films, which hadn't happened not even in Holland for a long time. That was important. That was the beginning, I think, of sort of reappearing again.

I think what I don't see now is the materiality of film. I mean of course, with digital it is much more difficult to get the grasp of materiality. There is no materiality, I think. Yes, and everybody is now working in digital because you can't pay for 16mm. You can still work with 8mm, sort of, but even that has become really expensive – that's a factor.

Nina Danino:

It doesn't have to be analogue necessarily but how do you think of material practice in how you are engaging with medium and the means of production? It doesn’t exist, quite in the same way anymore.

Barbara Meter:

No, no.

Nina Danino:

Because it's more about the content and the window, we're talking about.

Still

from Barbara Meter, From the Exterior

(1979).

Copyright

Barbara Meter. Courtesy of the artist.

Barbara Meter:

Exactly, exactly, yes.

Nina Danino:

Do you think that there is a reinventing or working with experimental film now, or do you think it emerged out of a particular context?

Barbara Meter:

As far as I can tell, it's the latter. I think it is a very specific time and a specific mode, a specific way of thinking about film which was then. It lasted maybe till the end of the eighties or something, I don't know.

Nina Danino:

As a context it was probably up till the eighties or early nineties, until the London Film-makers’ Co-op [LFMC] was not as strong anymore. For me it continues as forms of practice, but in analogue it’s more difficult because the production has to be independently done. Also the exhibition context shifted to the gallery although the knowledge and critical context which is so much a part of it is still there – like now in this conversation. Again, it was always perceived as an alternative film culture. But there are many experimental film festivals, cinema programmers and publications. Research writing about it is growing so that’s why I thought we should do our own by writing about it ourselves. I agree though it is very much a specific position and way of thinking about film.

Barbara Meter:

Of course, in Holland it was never so strong, so it might have been different in England and in America. In France it is much stronger than here. I mean each week they show experimental films at Light Cone.[31] Also, in America, it is much stronger than here. Here, they sometimes call films which are a bit strange experimental films, when it is not experimental at all.

Nina Danino:

In Britain it is called artists’ moving image which is primarily shown in the gallery and museums in installations.

Barbara Meter:

There's now an exhibition which is very nice in the EYE Museum [Amsterdam]. It's a pity you have to go. It's by Francis Alys – a wonderful exhibition. It's art, it's film, but it's not experimental.[32]

Nina Danino:

Can you say what experimental film means to you, then?

Barbara Meter:

It gives me freedom. It's the freedom – Maya Deren said that somewhere as well.[33] You know, I didn't have to be dependent on producers or money or a crew or anything. It gave me the freedom of handling my own camera which I feared but I could do it, and which enabled me to express myself in a way that I could do when I was a writer or a painter. So, it’s just a very personal way of making film. You had to do it in your own way. You don't have to say to a cameraman, “Oh you have to go to that angle and that light”, you can just do it by yourself so that spontaneity is a big thing.

I also became conscious of the fact that the anti-illusionist way of thinking was very much what I agreed with. Not that I do it all the time, but you know that whole idea that you are conscious of the fact that film is not a record of reality. It has its own interesting and specific characteristics. That is what experimental film brought forward for me, to look at it as anti-illusionistic and anti-mystification which are really the same. I think that is very healthy and good.

Nina Danino:

Deconstructing the apparatus and creating a reflective approach I suppose.

Barbara Meter:

Yes, that's very well put, yes. That is what I have here.

Nina Danino:

And taking it somewhere else through the subjective.

Barbara Meter:

Very important, which is not at the moment discussed at all, which I think is a pity and maybe it becomes again in a different form but, yes. So, I think for me theoretically that was very important.

Nina Danino:

You have had a long career. You continue to make films, you are making documentaries now. What are you making currently?

Barbara Meter:

I am. It’s a documentary, perhaps the title will be Nachtlicht or Light of the Night, something around this. It is about a school called Bunce Court in Kent. It was a school which originated in Germany and was re-established in England in 1933. It hosted mainly Jewish children. After 1938, after the Kristallnacht, many more children came with the Kindertransport.[34] I wasn’t part of the Kinder transport but after the war through family connections, after the first visit in 1948, I went to England by myself. I met a boy there whom I still know, with whom I fell in love with some years after. It is both the story of the school and a love story of two young people. In this film two elements are combined, it is the ‘first love’ experience I had when I was around 14 and the history of a Jewish boarding school. These two are entwined. All in Kent near the beautiful white cliffs and green hills and woods.

I have to have a producer because it’s more expensive than what I usually do. They thought that it would be okay for television and in Holland there is a special Jewish broadcaster. They are interested in showing the film and will contribute. It's 75 years ago that the Netherlands was liberated from the German occupation, the vrijheid, so there is interest in stories that witnessed the war (and escaped it in this case).

copy_cropped.jpg)

Barbara

Meter at her Amsterdam house and

studio (2020).

Photo:

Ewald Rettich (2020). Courtesy of Ewald Rettich.

Nina Danino:

So, I come to my last question. You spoke about making the films you dreamt of. Have you made the films you dreamt of?

Barbara Meter:

Some, the film Ariadne is one of my favourite films of my own. I don't know if that comes across at all, but it is supposed to be about being in love and expectation and an atmosphere of quiet. You don't know whether it's really happening or not and he leaves you in the dark. That whole sort of (breathes hard) and the Schubert is there because the song has, you know, this disquiet of movement of emotion. I think that has been an expression of that feeling; maybe not for other people, but for me it has.

Nina Danino:

Thank you Barbara for this talk with you.

Barbara Meter:

Well, your questions are so precise and made me think. I don't think I've answered all our questions.

Barbara

Meter and Nina Danino, at Barbara Meter’s house in Amsterdam (February 2020).

Photo

courtesy of Ewald Rettich (2020).

_____________________________________________________

Biographies

Barbara Meter finished studying at the Dutch Film Academy in 1963 and then undertook an MA in film and video at the London School of Printing in 1995. Meter was co-founder of the Electric Cinema in the early 1970s, a bastion of Dutch experimental cinema. Throughout her career, Meter made many experimental short films, including feature films and documentaries, whilst also curating film programs and undertaking teaching and lecturing on film.

Nina Danino was born in Gibraltar. She is a Reader in Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. She studied Painting at St. Martin’s School of Art and Environmental Media at the Royal College of Art, London. She was a member of the London Film Makers’ Co-operative in the 1980s, a member of the editorial collective of Undercut: The Journal of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative (1981-1990) and co-editor of The Undercut Reader (Columbia University Press, 2003). Her films have been shown worldwide and premiered at film festivals and broadcast on television and a retrospective of her work took place at Close Up Cinema, London in 2016. MARIA (2023) is her fifth feature-length film. Her soundtracks feature vocals, singing, readings, narration and music in her own voice and in collaboration with singers and musicians. Her recent work crosses into stand-alone audio, live performance and studio recording.

_____________________________________________________

Select Bibliography

Bittencourt, E. 2017. “Flickering Portraits: A Barbara Meter Retrospective.” Art News, 27 April. Accessed 14 April 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/flickering-portraits-a-barbara-meter-retrospective-60046/

Close Up. 2016. “Up to the Sky: 4 Films

by Barbara Meter,” Close Up Film Centre,