Part 5 (of 6)

A

camera of one’s own: Dramaturgy, Super 8, expressionism, chronicles of the

London Film-makers’ Co-op

Anna Thew in conversation with Nina Danino (2020/25)

Still,

Anna Thew filming in Poems and

Constructions II – L’Isle sur Serein (2008).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

_______________

Shaped from

an online conversation and subsequent emails between the artists during and

after the first COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in the UK, this text captures an

extended and ongoing conversation between Nina Danino and Anna Thew, who have

known each other since the 1980s, when they were both members of the London

Film-makers’ Co-operative, where Anna Thew was Distribution Organiser

(1980–1982). They recorded this discussion on 10 May 2020 and later revisited

their transcript in 2023/2024/2025.

________________

Anna Thew has worked collaboratively with friends, fellow artists

and filmmakers on her films from the time she was in her final year at Chelsea

School of Art in 1978. She likens her practice to belonging to a theatrical

troupe. In her authored films there are strong group and collaborative dynamic

production methods, where participants take up roles and parts in the films.

There is a strong performative and live aspect, which is not scripted but

invited through mise-en-scène, staging, lighting and camerawork.

Anna Thew’s films often are

strongly referential of other experimental films. They follow her erudition in

Italian Literature, Renaissance Art History and film knowledge, with a

chronicler’s focus on detail and mapping artists around the London Musicians’

Collective and the London Film-maker’s Co-op in the 1980s. Anna Thew operates

the camera and is the maker of her films but she crosses roles, also becoming a

performer and member embedded in the group by appearing in her films. There is

a strong aspect of being in front of, and looking through the camera, framing

events and scenes, with the camera as the impetus and centre of this theatrical

environment. Being a subject in the film slips into being an actor through

adopting parts and roles, or being herself as a filmmaker. Roles are always

interchangeable, performative.

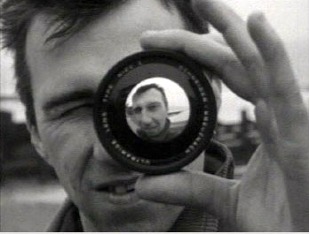

In her works, the camera is

frequently hand-held, handled and a central eye. In the context of this wider

interview series examining Nina Danino’s conception of the ‘intense subject’ in

filmmaking, it was not easy to find an individual subjectivity in Anna Thew’s

collective movability, although the collective can and does form a body in her

works. There is strong aspect of self-inscription. However, a subjective thread

is discernible. In this interview discussion, the piano emerges as an

instrument of solo moments of nostalgia through both Anna Thew’s playing, or

playing by other pianists. Her love of piano and music emerges as a strong

presence of a singular introspective activity: the path also followed by Nina

Danino and Anna Thew as their discussion progresses.

Extract from an email sent by Anna Thew to Nina Danino (28 March 2020) – There's perhaps an urgency for us to get our archival act together, “Before we too into the dust descend” and the ether may not be the best vehicle – a solid tangible tablet, a desirable tangible heavy book – as if it’s as bad as the Black Death of 1348 that reduced the population of Europe by over two thirds, I doubt that anyone is going to be trawling through a little known group of experimental women film-makers' mountains of 6TB drives – not even on LTO yet – with only a 3 year guarantee – if we snuff it from the virus…

________________

This conversation is one of a series of six discussions undertaken

by the filmmaker Nina Danino in 2020. They were revisited and edited in

2024/2025 when they were published online.

Please note that the opinions and information published here are

those of the speakers/authors and not of LUX or the wider research team and

institutions involved with their funding, transcription and publication.

Published online by LUX, London (2025)

Editing and research: Claire M. Holdsworth (2020/2025)

________________

Conversation

Edited transcript of conversation

recorded remotely, 10 May 2020 (London)

Later compiled/edited via email

(2020/23/25)

_____

Nina Danino:

These

conversations are on the theme of inscription and the subjective rather than

going into interpretations of individual works, but to take some themes in the

work and the practice to gain an insight into how and where the inscriptive, or

inscription might be in experimental films. Could we talk about the singing in Eros Erosion (1990). Is it you singing

at the end, over the shots of the

Alps from a plane?

Anna Thew:

It’s a friend, American

beat poet, Carlyle Reedy singing My Funny

Valentine. I secretly recorded her playing my piano after her wild young

lover, musician, Pete Smith tragically died in a fall leaping from roof top to

roof top. It’s Carlyle’s voice that you hear over the ropes and boats in Naples

Port describing how she came to the mortuary and found the dead body of her

lover, “and I saw the dead body and I

knew it was dead”. Her voice is filled with grief. Then that Rogers and

Hart song is picked up at the end of the film over the Alps.

Nina Danino:

It is haunting. There

is piano music also over the scenes in Naples. Is that you playing?

Anna Thew:

I did play a little

Domenico Scarlatti sonatina (Longo

No.104, K.159, Allegro), over the Naples Street scene. So you play and make

a mistake and then you can cut (the mistake) and join the 16mm magnetic sound.

Domenico Scarlatti and his father, Alessandro Scarlatti were from Naples. So, I

played this little quick Neapolitan bit. Then I play a drift of Benjamin

Britten over the moors. Otherwise, what’s important in Eros Erosion, is the use of resonant abstract piano sound, which I

made inside my Dad’s old Steinway upright piano. I collaged sections. Some are

slowed, so you hear ‘Vroom…’. Then

sometimes you hear a bright tiny tinkly sound. I actually layered them across

one another, so you get a recurrence of that prepared piano sound throughout

the film.

Nina Danino:

The

piano provides the soundtrack to many of your films, you often talk about your

music and what you are practising and playing on the piano.

Anna Thew:

The piano, my Father’s

piano, has its own story that I was beginning to map on film in 2010/11. It was

really going to be an installation called Stolen

Time, from when I had the action restored. In music, the expression tempo rubato means stolen time… like

gathering something rather rapidly. It’s not accelerando. You’re stealing

time. You’re shrinking time. It’s a great phrase. I’ll send you the

quadraphonic soundtrack, which was played from four speakers with a rough cut

double screen at Contact Festival, Apiary Studios, London (2016). My Father was

a miner’s son from Castleford and everybody in mining communities up North,

almost every household had a piano, a violin (fiddle), or a flute. My Father

played and sang as many working class families did in the 1930s and 1940s

before television killed it all off. When he was posted to India during World

War II, my Mother went out – she didn’t know anything about pianos – and bought

this rather wonderful Steinway vertegrand

(upright-grand) from a lady pianist in Sheffield. It’s overstrung. It’s got

long strings and has a really resonant tone… a fantastic tone in the bass. When

my Father could no longer play, he let me have the piano. We had it restored in

the Steinway Marylebone (Lane) workshop in 2010/11 and Christopher Hughes and I

documented the process over 3 months, on film and Hi-band. Dad’s piano’s been

part of my life. It was always in the living room, and it has a wonderful tone.

It’s a bit like the Pied Piper of Hamlin

that draws you in… My Father and Mother both sang. My Father had a beautiful

bass voice and my Mother was a contralto. People would get together round the

piano and sing. I started piano lessons when I was very tiny. I hated the

teacher so I would lock myself in the outdoor loo in this School House in

Woodlesford near Leeds and kick and scream and refuse to go. Then he stopped my

lessons.

Nina Danino:

You

said you had been playing Duke Ellington’s Solitude

(1934). How much is playing a part of your life as well as its role in the

films.

Anna Thew:

I actually never

stopped playing the piano. I taught myself to play from learning to sight read.

It’s always been at the centre of my life, but more recently when I started

having lessons, it actually became even more critical. But in all the films

there is a little bit of piano music and piano sound.

Nina Danino:

In

Hilda was a Goodlooker there is a

scene with you as a cabaret singer. This is intercut with images of Sheffield,

workshops and steel works. Can you talk about your role as a cabaret singer in

the film.

Anna Thew:

Now in Hilda, I’m just doing what we used to

do. I mean, at Christmas my sister and I used to dress up and put balloons down

our dresses like Hinge and Bracket

and we’d sing, “Who is Silvia, What is

She?” (Schubert, An Silvia,

1826). So I dressed up for Hilda. It

was important because Hilda was about

family and home and my mother mentions Harry, my mother’s half-brother, “an’ ‘e used to croon at the piano” and “’is little dog Floss used to croon along with ‘im”. In Hilda, I play and sing, “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” (Cole

Porter, 1936), meaning I’ve got Sheffield under my skin.

Nina Danino:

The wide shot of the

cabaret singer is intercut with close up shots of you scratching your arm or

your leg which disrupt the performance and you and the pianist, who is Martin

Lugg, stop to have a cup of tea, which is comical.

Anna Thew:

I was spoofing. I’m

scratching my arm because I’ve got Sheffield under my skin and I’m scratching

my leg. So it’s just a spoof, but I’m not singing how you’d normally hear it

sung.

Nina Danino:

How would you hear it?

Anna Thew:

I’m a cabaret singer in

that film and the type of voice I’m using, is because I have a rough contralto

voice. At the time I was a smoker and I used to be able to do and still can do

a very effective Marlene Dietrich impersonation. My sister and I used to

compete about how we’d do a turn from Der

Blaue Engel (1930), “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuâ auf Liebe eingestellt…” (Falling in Love Again).

Nina Danino:

It strongly makes me

think of Germany and Berlin in the 1930s?

Anna Thew:

I just did what we used

to do at home. Martin’s Father was a pianist and organist, so Martin’s trying

to look like his Dad. He’s got these spectacles. We were learning. We weren’t

very good at lighting, so it looks as if the shadow of the microphone is sticking

out of the top of his head [laughter].

Nina Danino:

The sound drops out in

places and there are a series of halting phrases. The singer is also at points

detached from her own voice.

Anna Thew:

Well, the films play

with synchronisation. I hardly ever use sound synch in my films and in that

scene in Hilda, there’s no-one behind

the camera. We’re in the old London Musicians’ Collective. We stuck the Arri BL

on the tripod. We raced in front and Martin’s pretending to play the piano. I

rush over, turn the camera on, then rush and turn the sound recorder to ‘PLAY’.

It was a Nagra III, not a Nagra IV with crystal synch, so the playback was out

of synch. Fortunately, we’d filmed ourselves having a cup of tea and scratching

my leg, just in time.

Nina Danino:

Were you thinking of a

method of filming which is Brechtian perhaps and the results are disrupted?

Anna Thew:

Yes, well the use of

the piano and the way in which you introduce those pieces, because you’re

having to assemble them and you’re not doing a whole performance, you’re using

a fragment and you drop it in and you take it back out again. I think with Hilda, what one was doing, was using and

playing with all the things you like to have. It was an intentionally

deconstructed narrative.

Nina Danino:

Cling Film (1993), you perform the

role of Rose Hobart in the black and white silent film East of Borneo (1931), which is the found footage which Joseph

Cornell used in his blue tinted film, Rose

Hobart (1936). The tint of the film and the mannerisms of the actress are

so funny. Did you want this to be a reference to early studio film within an

avant-garde film within an experimental film and so on?

Anna Thew:

Yes, that’s the

reference to Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart

(1936) which was the earliest

found footage collage film.

Throughout Cling Film there are

references to avant-garde film. It’s a little game that you can play. Rose Hobart is one of my favourite

films. I couldn’t afford the copyright from Anthology Archives N.Y. My

performance is not really like Rose Hobart, more like Pearl White. The

soundtrack is Holiday in Brazil (1957).

That’s the sound track that Joseph

Cornell played with Rose Hobart. It

was a Latin tune that was in vogue at the time. Joseph Cornell never put it on the film. The reel-to-reel sound was

always played separately from the film. So I appear as Rose Hobart, who’s a voyeuse

and I’m re-acting with alarm to the action (sex scenes, crocodiles and

volcanoes). Holiday in Brazil was out

of copyright. I was able to purchase the rights for very little, but we’d

transferred it both forwards and in reverse and that is collaged in. There’s a

snatch of Bela Bartòk over the Nosferatu

clip and some staggered chords dropped in from Gershwin’s The Man I Love, but

infringement and playing with copyright is a game throughout Cling Film (1993).

Nina Danino:

More direct is the

voice over of your mother in the soundtrack of Hilda was a Goodlooker where she is talking about her memories of

her family.

Anna Thew:

My Mother would have

loved to have been in the theatre and she was very good at storytelling. She

was quite theatrical. She used to read poetry. Had she not been from a lowly,

humble background, she probably would have been like us and she would have gone

into drama. My Mother tells the story of how she dresses up in an orange coat

with this (rabbit) fur collar and walks up the marble staircase like Lady Muck and she tells of her brother

Harry who was dark and handsome, how she was posing as his girlfriend going to

the Scala Cinema in Sheffield, which was all marble. We filmed this scene in

the Cambridge Theatre on Cambridge Circus, where they were showing Les Misérables. I used the marble

staircase there. We only had an hour to light it. So I waltz up the marble

staircase “like Lady Muck” and I play

my Mother (lighting/camera Ian Owles, Marek Budzynski).

Nina Danino:

You said in our e-mail

exchanges prior to this conversation that the reason you made the film was

because, “My Mother had always wanted to be near to the theatre […]. Now that

she was retired I would help realise her dream to be near to the theatre.”

Anna Thew:

My mother died in 1983

during the making of the film. I play my Mother play-acting, my Mother’s dream

of being a diva, of being an actress, of being in the movies.

Nina Danino:

Were you always going

to play the part of your Mother as a young woman? There is also Hermine

(Demoriane), who plays your mother’s half-sister Hilda. Hermine was herself a

chanteuse in the London performance art scene which in turn mirrors you as a

singer. In these female roles the real women and characters play each other.

Anna Thew:

No,

I’d intended my Mother to re-direct scenes that I’d imagined wrongly. There’s

also singing of Kurt Weill and other variety songs. At Chelsea, I was involved

in this theatre group and I wrote some song music for the staging of Brecht’s The Messingkauf Dialogues, after Hans

Eisler’s “Ich hab’ mein’ Sohn die

Stiefeln und das braune Hemd geschenkt” [I sent my son the boots and the

brown shirt].

Nina Danino:

Kurt

Weill, you use Brechtian alienation techniques in Lost for Words (1980) and in the singing and assemblage in Hilda was a Goodlooker (1986), as we discussed, where you perform

Cole Porter’s song in the style of voice of Dietrich – one of her most famous

roles – the avant-garde theory of montage is invented in this period but it is

also a shadowy period of history.

Anna Thew:

I studied

German language and literature, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Heinrich von Kleist,

Rainer Maria Rilke, Goethe naturally and Bertolt Brecht’s Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder [Mother Courage and her Children]

(1939) and Erwin Piscator.

Nina Danino:

You were studying

Painting at Chelsea between 1974 and 78 but said you were involved with a

theatre group. Was it part of the course? How did this influence your films?

Anna Thew:

There was a Brechtian

theatre workshop lead by Alexei Sayle (ex Chelsea) and my old thesis tutor,

Yehuda Safran. Actually the tutors were so into it that we had about four

tutors and four or five students and we staged these pieces (by Bertolt Brecht

and Garcia Lorca). I wrote the Hans Eisler sound-alikey tunes with impossible

intervals to some of the Brecht poems. So film for me, was an opportunity to

involve all those aspects. The first film that really inspired me to pick up a

camera was Anne Rees-Mogg’s Real Time

(1974).

Nina Danino:

You

have called the teacher and film-maker Anne Rees-Mogg, the Great Aunt of your

film family, who changed your life with her film Real Time.

Anna Thew:

In

Real Time, she uses words. She uses

accounts. She uses diary, the family and she uses direct experience. She also

uses songs that she likes, like, “I would

sit there in the gloom of my tiny little

room, if I had a talking picture of you-ooo, you-oooo!”, as she drives

Westwards and home and it’s so, so poignant. It’s like OK, you can do this. You

don’t have to just do painting and

because just painting was getting to be a problem… I didn’t realise that I

quite liked words as well, you see,

because I was steeped in literature. And then I started to do word paintings. My first word paintings, the

really big diptychs (2.4m x 1.2m) were layered conversations about having Dad’s

piano, Wordpaintings (1982).

Nina Danino:

In Eros Erosion (1990), as we said earlier, ends with the shot over

the Alps and it is set in the back streets of Rome and Naples. Italy and

Italian literature permeate many of your films. Eros Erosion re-tells Lisabetta’s story from Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1350–52). Italian is

heard recited in quotes of poems, readings and words, in text and on the

soundtrack.

Anna Thew:

I’ve always been

interested in words. I talk all the time. I’m a chatterbox so there’s no way

that I’m not going to be interested in words [laughs]. I always liked poetry

and song. I wanted to be a painter all my life. I went into languages, not

because I wanted to, but because I couldn’t do Art A Level at the school I

ended up at, Don Valley High, where they were trying to up their Uni figures. I

got into Manchester to do French and German BA Hons. I noticed that if I

studied BA Hons Italian Studies, I could do Art History as well as literature.

I started studying Italian in earnest and got onto the Italian Studies course.

Philipe

Barbut as Lorenzo and Toni Dominici as the brother of Lisabetta in Anna Thew, Eros Erosion (1990).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

How did you go to a

Fine Art course?

Anna Thew:

Through

Alastair Smith at the National Gallery and my old Professor Giovanni

Aquilecchia at Bedford College, London.

Alastair was my Italian Art History lecturer at

Manchester. He later became director of Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester. I

was applying to the Courtauld Institute to study MA in Quattrocento (1400-1500)

Italian Renaissance Art and both of them, who were going to give me a

reference, said the same thing,“Why don’t

you just do what you’ve always wanted to do and apply to do painting?” So,

I did. I went to Chelsea and I did Foundation and then FA Painting. There were

these wonderful opportunities, meeting people like Anne Rees-M on the very

first day, when rather than doing any painting, we were sent out with a stills

camera, a roll of Agfa Dia-Direct film and a tape recorder to document our

first day at Art School. We did a slide-tape piece, which we then re-filmed on

Super 8. Slide-tape and Super 8 were introduced very early on, as were film and

photography. These were new things to me and there, they were offered on a

plate in the Foundation year at Chelsea. When I was painting, mostly abstract

very early on, I was doing collage and that collaging process is in the films

and the ways in which I edit are the things that one learned and really loved.

I was very into Dada (1916). I really liked the notion of chance procedures

which are used almost entirely through my film/editing process. I might have a

plan, but then there will always be an element in which you will have a kind of

automatic writing, an automatic drawing, an automatic choreography/calligraphy

of the camera. Then once I started to return to figuration in my large dancers’

paintings and chiaroscuro drawings in series, I began to film.

Nina Danino:

In

our exchange of e-mails prior to this discussion, you write that “Playing can

lead to a kind of self-fashioning and create a sense of community.” And that,

“Often also the enlistment of friends and those willing to help plays a role in

experimental film. Sometimes this becomes an important documentation and

history in itself. Often those participating become themselves known in their

own right, lending the activity validation.” Can you

say more about the collaborative aspect of your practice which is very strong,

like being a ‘family of travelling players’, the methods of the theatre are

very forming and you also refer to your use of Brechtian acting techniques in

your first 16mm film Lost for Words,

“a parody on the urban wasteland film, where a little girl recites Karl

Marx and the last man on earth to read and write is interviewed”. The mix of tutor performance artists and

film-makers at Chelsea were part of an

experience of collective practice that appealed to you.

Anna Thew:

Well, there were

wonderful people that I met there like Keith Milow, who was one of my tutors,

whom I’ve actually met up with recently again. He was doing subversive abstract

reliefs with crosses at the time. He was quite important to me. Then someone like

Ken Kiff who worked with the subconscious. It was more the tutors like David

Medalla, Ron Bowen and of course, dear Anne. I quickly ditched out of the

Manresa Road building, because I became friendly with Jock McFadyen on the MA

down at Bagley’s Lane. The undergraduates’ studio was a huge empty studio. So

he said, “Why don’t you come down to Bagley’s Lane?” So I went down there and I

was doing huge abstract layered paintings. I mean, they were very big

triptychs, around 18 foot across, washing the paint off with hose-pipes. They

looked a bit Frank Stella like… and I loved Elsworth Kelly.

Nina Danino:

That gives a really

good description of the art school experience of the 1970s. We were almost

entirely self-taught. There was no pedagogy as such when I went to St.

Martin’s. What was your experience of the studio?

Anna Thew:

I started making a

Super 8 film of 35mm slides of men’s faces, called From Face to Face (1978). I’d

started taking their pictures with b/w Agfa Dia-Direct (slide film). In a way,

I was playing around with the idea that men actually really liked to have their

pictures taken, to be desired, like women. I had three particularly handsome

ex’s and then there was riveting David Medalla. So there was one gay person in

there. I went to Paris to film my first love, Sandy (Spencer). His best friend

Alain (André) was a clown who appears in the film. He takes the mickey out of

the guys having their photographs taken. At one point, a friend (film-maker,

Debbie Gillingham) and I were on the sound track, saying they weren’t really

good enough, like a casting. In the end, I decided it was too mean and I wiped

the track. Now the film is just faces of these men you love to look at, that

look at you through the camera. In that film, it’s how men become objectified.

Stills

(left to right) of Karel Zuvaç, David Medalla, Sandy Spencer and Martin Angel

in Anna Thew, From Face to Face (1978).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

In Laura Mulvey’s

concept of ‘to be looked at-ness’ woman is coded as the object of the male gaze

and it isn’t supposed to be symmetrical with a female gaze on a man. Some men

in your films present themselves as ‘to be looked at’ like sailors – is it a queering

of the look?

Anna Thew:

No, it’s not queering.

It’s woman-ing. This was the female gaze. I wanted to show that men

enjoyed being objectified… desired…

Nina Danino:

Films are all about

positions. How did you start making films?

Anna Thew:

I started filming the

opening scene of Lost for Words in

1978, when I was still at Chelsea. That was the wasteland scene. I had a lot of

help from Anne Rees-M, of course. I was also very friendly with artist Jock

McFadyen, who was making films. So was Richard Welsby, who was in the same year

as me on the BA Hons course, and Ian Owles, then at the RCA. So there was a small group of us who made film and did painting.

People were swapping from one to the other and there was a small community.

Jock had us in his film The Case

Continues… (1977) with Helen Chadwick and Giles Thomas. I was a cloud. Then

I was in a film and my friend Monica (Molnar) was also in Jock’s Close Encounters of a Martian Missionary (1976)

which was very picaresque. I don’t think he probably knew about the American

avant-garde, James Broughton or Sidney Peterson, like The Pleasure Garden (1953) with Hatti Jacques, or Loony Tom (1951), or The Lead Shoes (1949), but there was

certainly a very, very close link, because Jock did these paintings which were

sort of quirky with subtitles. We were all very much into semiology, Roland

Barthes and the meaning of the image and the play with word against image. That

was very current at Chelsea in particular. Jock was hugely influential on me in

the beginning.

Nina Danino:

What made you decide to

perform in your own films? In Behind Closed Doors (1988) you are in front of the camera and also

director, where you become the Christ-like figure from the Raphael painting, The Deposition (1507), where you are

carried around naked like a corpse. There are quite a few people, film-makers

involved as dramatis personae

including Derek Jarman, Kenny Morris, Julie Osborne, Adam Elliott, Steve

Farrer, Emina Kurtagic and Richard Heslop (James Mackay was camera operator and

Christopher Hughes was lighting camera for that scene).

Still

from the final ‘Deposition’ scene, Anna Thew, Behind Closed Doors (1988).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Anna Thew:

It was just an

automatic thing to become involved. If you’d actually been involved in language

and you played the piano and you used your voice and you performed, because

I’ve always been a bit of a performer, so you do that and then you use

yourself, where it is too difficult for others… to be a naked corpse being

dragged over a pile of rubble.

Nina Danino:

Was theatre

and performance also part of early expanded film experiments ‘somewhere between

theatrical and performance art’?

Anna Thew:

Well, yes, with Anne,

we went up to the Co-op. We went to see Jock’s film. I think it was Close Encounters of a Martian Missionary in

which I was in jumping in and out from behind a tree and there was a chase

around Battersea Park… a cupboard with its doors opening and closing so that it

looked like a human being, and it was very

silly. Yes, we’d go up to the Co-op with Anne in her Ford Cortina. So I had a

few little sessions where I went to see other people’s films at the Co-op, when

it was at the Piano Factory in Fitzroy Road, Camden. That would’ve been in

1977. It was Anne who introduced us to the Co-op. She introduced every student

of hers, Chris Welsby, Richard Welsby, Renny Croft, David Pearce, Ian Owles,

Jenny Okun, Guy Sherwin, Willi Keddell, Tony Potts, Nick Gordon-Smith, Mark

Greaves, Mark Sheehan, me, Jock. All of those people were at Chelsea and they

were all posted off up to the Co-op by Anne, who believed in the Co-op, still

(from 1966).

Nina Danino:

You say

that before 1980, there was almost no theatrical performance at the Co-op. Can you talk about the overlaps

between the LMC and LFMC? In On Leonardo

(1977) you combined your performance and slide/tape projection of the Mona Lisa

with “burning screens and readings from Leonardo Da Vinci’s Trattato della Pittura [Treatise on

Painting]”. Did you engage with expanded screen and collaborative work with

artists in other fields like music or theatre in the context of the Co-op?

Anna Thew:

Yes, there was David

Medalla and his Artists for Democracy,

Whitfield Street (squat, 1976–1979), where I did my first performance in 1976….

and where I met Tina Keane (from London Video Arts), Harriet the stripper, beat

poet Carlyle Reedy, musicians and performers Anne Bean, Stephen Cripps (from

the London Musicians’ Collective), dancer Atilio Lopez from the Lindsay Kemp

troupe, and at the Co-op, Paul Burwell who was on the London Musicians’

Collective Exec. and was Annabel Nicholson’s ex.

Nina Danino:

The Co-op was based

on16mm, did you use the workshop?

Anna Thew:

My very first film, From Face to Face, was Super 8, with

sequences re-filmed from b/w slides, but my first 16mm film was Lost for Words. I filmed the first

wasteland scene and Ra, my daughter, reading from Marx’s Communist Manifesto when I was at Chelsea, as I said, but then I

carried on making that film at the Co-op in 1979-80. When you worked at the

Co-op, you made a cup of coffee and you chatted to people, then you were stuck

in your edit room with your pic synch, which wasn’t even a motorised one. It was

just a winding pic synch. You got really bad eyesight after you’d finished

looking at the tiniest little screen with one eye and so I edited Lost for Words there. It was when I was

at the Co-op editing that I met James Mackay, who was doing the Cinema, and

Mick Kidd (BIFF cartoons), doing the Distribution. They then persuaded me,

along with Jock, who was in and out of the Co-op at that time too and living in

our house, that “it’s about time you got

a job and there’s a job going in Distribution”. So they persuaded me, these

three guys, to apply for the Distribution job.

Nina Danino:

Can you

give a window into that context of your time distributing? When in distribution were there

particular initiatives that you set up? You launched

the annual Distribution Preview Show in 1981 and were involved in the Summer

Show in 1982. The Summer Shows were so important to artists. I showed my

RCA film First Memory (1981) at the

1982 Summer Show, it made all the difference to have a cinema exhibition

context for your work.

Anna Thew:

I started working in

distribution in 1980 and that’s when I met Peter Gidal. I wrote about it in Between The Lines for the 20 years of

the Co-op catalogue, LIGHT YEARS (1986).

He was sitting next to me at the 1980 AGM and he put forward the motion that

was voted in, that at least 50% of women should be on the Co-op Executive

Committee. Yes, that was my first AGM.

Nina Danino:

The LFMC as a feminist structure that’s very good. There had been

a split and Felicity Sparrow, Lis Rhodes and Mary Pat Leece founded Circles in

1979, but Peter Gidal was very feminist and both he and Malcolm Le Grice

proposed 50% women, as you say. In another interview I have done for this

series, Barbara Meter quotes Annabel Nicolson, who said the men at the Co-op

were natural allies. The men founders were central in bringing the structure to

50% representation in the organisation.

Anna Thew:

At that time, in

Cinema, you were only there for a year. At the 1980 AGM, they voted Steve

(Farrer) in for the Cinema. I was voted into Distribution and Jeanette Iljon

was voted into Workshop with Nicky Hamlyn. The two workshop organisers would be

there for only two years and would overlap. So each year they were voting in

new organisers. I started working with Steve in 1980, but interestingly there

had been an anti-feminist débacle over the Susan Stein affair the year before

and almost the whole executive had resigned, like Deke (de Dusinberre the IV).

It was quite interesting because Susan, who had a crush on Steve, had been at

the Royal College (of Art) and she wanted to do the Workshop job, but she’d

also started as a student at St. Martin’s and the men said she couldn’t hold

down the workshop job and be at college at the same time. She replied that

Steve had done the workshop when he was at the Royal College. Guy Sherwin did

the workshop when he was at the Royal College and William Raban! “There are

men that are allowed to do the workshop when they’re at college, so why can’t

I? It's only a part-time job.”

Nina Danino:

Susan Stein recently

posted (on Facebook) a portrait of herself at this time at the LFMC in front of

the Debrie contact printer holding folds of film like a bouquet of flowers.

Anna Thew:

So, the whole thing

blew up and most of the executive had resigned. So, when Steve and I started,

there were only two people (film-makers) on the executive. There was a woman

called Serena Rule from the Royal College, and I think Paul Botham.

Nina Danino:

Can I say something

about her because she was friends with my friend Tony Mucklow, when we were at

the Royal College. The RCA film school was factionalised into camps, feminists,

Carolyn Spry, Robina Rose, the structuralist film-makers led by Peter Gidal,

and the independents such as Steve Dwoskin, the political activist film-makers

such as Chris Reeves, whom I had come across at St. Martin’s Painting

Department and the fiction directors. I was surprised when I met Serena Rule at

the Co-op (she was on the Executive) because she was in the fiction and

documentary camp, like Tony Mucklow I think.

Anna Thew:

She was the treasurer.

She was a treasure. Anyhow, at that time, all the people who were on the Co-op

Executive were film-makers. As we

didn’t have really a functional Executive, we didn’t have a boss. We got on

like a house on fire. So, there was me, Nicky [Hamlyn], Steve [Farrer],

Jeanette [Iljon] and Mick Kidd.

Nina Danino:

We

kept the Undercut bits and pieces,

galleys etc., in the Distribution office. We used to meet there on Saturday

mornings, when it was unoccupied. Nicky Hamlyn who was in the Workshop, was

also on the Undercut editorial

collective. I joined in 1982 at the same time as Michael O’Pray and A.L. Rees.

Anna Thew:

Nicky would go, “Roland Barthes, the silly old fart!” He

had a very sort of anal sense of humour and he used to chuckle. Nicky and Mick

Kidd, who was a truly co-operative person (BIFF with Chris Garrett), he was doing t-shirts and fanzines from the

start and he made Standard 8 films and he loved Kurt Kren. A lot of folklore

came down to me through Mick Kidd, who was a great storyteller, and we all

worked together very happily. He was a very nice guy. He was so honest.

Nina Danino:

Undercut published Mick Kidd (BIFF)’s lampoons, ‘Understanding Media Part Four’ and

‘Win a Fabulous Holiday’ – Undercut

also had writing by and about artists.

Anna Thew:

I wrote about Sandra

Lahire’s films for Film Waves – Art in Sight (2002) after she died in

2001. I was asked to write about Anne [Rees-Mogg] and George Saxon and Steve

Farrer for the Arts Council British Film and Video Artists Directory (1995).

Then I got very annoyed, because they only allowed such a short text. Then when

it came to Johnny Maybury, they (David Curtis) allowed him to have three pages

and everybody else had a piffling little amount. But anyhow, yes, I wrote also

about David Larcher’s Eetc., (1987)

and Granny’s Is (1989) for Eyeball magazine in 1998.

Nina Danino:

Writing was very much

part of artists’ film practice. But probably out of necessity because as Sarah

Pucill says, feminist film scholars were not writing about women’s experimental

film. They were writing about Hollywood, and neither were art critics. The

structuralist filmmakers of the seventies wrote about each other. Materialist

Film has become almost the only record of the theory, through which to approach

the practices. It is structuralist film-makers writing about each other. This

ethos was carried forward into Undercut.

Anna Thew:

I was asked by Stephen

Thrower, a writer and musician, now with Ossian Brown as Cyclobe, and also an authority on horror films, particularly Dario

Argento and he’s a very clever guy. He’s good on theory and on almost

everything. He was with Coil and

appeared in Derek Jarman’s Imagining

October (1984). Steve wanted me

and Ron Peck to start doing a section in Eyeball

[magazine] on avant-garde film. I did two things. One was ‘Notes from the

Underground’. The other was, ‘A Profile: David Larcher’ (Issue No.5, 1998). In

‘Notes from the Underground’, I talk in some detail about the importance of Lis

Rhodes’ abstract films Dresden Dynamo

(1971) and double screen Light Music

(1975) and the pulsating rhythm as bands of different widths travel into the

optical sound track… the physical sexual energy that’s in those films. You

know, because she was in her youth when she made those films and somehow or

other, everybody’s going to respond to those films from a physical point of

view.

Nina Danino:

The clatter of the film

passing through the projector, the beams of light which the viewer can walk in

front of and interrupt, casting shadows and so on. It feels very contemporary

as an interactive installation also because the image and sound are abstract.

Anna Thew:

Yes, but in some ways

that’s the point. That’s what I’d call feminist.

Nina Danino:

Apart from editing Lost for Words, did you make other work

at the Co-op workshop?

Anna Thew:

Yes, Blurt and Shadow Film (1983) were processed, contact and optically printed

there. Behind Closed Doors, Hilda

were edited there. Scenes for Hilda,

Behind Closed Doors, Eros Erosion,

Cling Film, Broken Pieces for the Co-op, were filmed there. Sound

transfers, cameras, rostrum, through to optical printing (1979 - 2001). I

didn’t really start making films properly, until I’d left Co-op Distribution in

1982 and started teaching on the Film and Video at St. Martin’s. I was doing a

lot of drawing in my time off - big influence on Steve (Farrer) because as an

‘organiser’ you worked two and a half days a week. Mick Kidd and I had a

fantastic scheme where we did a week on and a week off. That meant that I spent

the whole week off painting and drawing. In 1981, I won a prize at the

Cleveland International Drawing Biennale and it was a rather nice amount of

money for a piece of paper that only cost 7p. I got £500 and so I bought a

Super 8 camera, a Bauer with a Schneider lens. It was one of the ‘top of the

range’ cameras. What was actually very important, were the films that you saw

and the people you came into contact with.

Nina Danino:

What films did you see?

Anna Thew:

All the films deposited

in Co-op Distribution, 1980 – 1993 and beyond… Stan Brakhage’s Murder Psalm, The Act of Seeing with One’s

Own Eyes, Deus Ex and Love Making I and II, Chick Strand’s Waterfall, Anselmo, Kulu Se Mama, Bruce

Baillie’s Mass for the Dakota Sioux

and Castro Street, Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks, Scorpio Rising, Eaux

d’Artifice, Derek Jarman’s Home

Movies I and II and B2 Movie,

Carolee Schneeman’s Fuses and In Quest of Meat Joy, Margaret Raspé’s Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, Cordelia Swann’s Passion Triptych and Der Engel [The Angel], Jo Comino’s Spleen, Anne Rees-M’s In Grandfather’s Footsteps, Alle Macht der

Super Acht [All Power to Super 8], Dore O’s Frozen Flashes, Manuel de Landa’s Itch Scratch Itch Cycle, Robert Breer’s Swiss Army Knife and Pigeons,

Michael Maziere’s Cézanne’s Eye and The Bathers and The Red Sea, Moira Sweeney’s Imaginary

I and II, Richard Heslop’s Death

Comes Creeping Through the Door, Ian Kerr’s Persisting, Post Office Tower

Re-Towered, Sally Potter’s Thriller,

Nicky Hamlyn’s Guesswork, Paul

Sharit’s Episodic Generation, T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G and Razor Blades, Kurt Kren’s Baüme

im Herbst [Trees in Autumn], Tree

Again, Mama und Papa and Selbstverstümmelung

(Self-Mutilation), Georges Rey’s La

Vache Qui Rumine [The Cow Chewing],

Chick Strand’s Kulu Se Mama, Anselmo and Waterfall, Martha Haslanger’s Circus

Riders, Ron Rice’s Chumlum, Ken

Jacobs’ Little Stabs at Happiness,

Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour, Andy

Warhol’s Kitchen, Couch, Chelsea Girls. Sydney Peterson’s The Lead Shoes, Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks, George Saxon’s The Emperor’s Mother, David Larcher’s Monkey’s Birthday and Eetc., Marie Menken’s Dwightiana, Vanda Carter’s Mothfight, Peter Kubelka’s Adebar und Schwechater, Matthias

Müller’s Aus der Ferne [The Memo

Book], Michael Brynntrup’s Liebe,

Eifersucht und Rache [Love, Jealousy and Revenge]… How many pages can you

give me? We had over 2,000 titles in Distribution from 1966/7 (to 1999) and I

programmed some 500 films at Chelsea from 1985 to 2006 and FLUX from 1994 and

on.

Nina Danino:

I’m

sure you have lots of stories about the Super 8 scene in London. Nights and events at B2 Gallery, Metropolitan [Wharf] and

Butlers Wharf and Derek Jarman etc. You had cameo parts in some of this

Super 8 scene. Super 8 were also associated with the

post-punk context of the nightclubs and music videos like in the work of John

Maybury. What was your experience of it? Super

8 hit strongly in the middle of the 1980s, didn’t it?

Anna Thew:

No, no, no, no,

absolutely not. It started in earnest in the UK in 1981. Jo Comino, who was

running the Co-op Cinema (1981–82), made Super 8 films herself. She made Spleen (1982) and she made a documentary

feature about Super 8 (shown on Channel 4). In Art Schools from the early

1970s, Super 8 was common currency. We had Super 8 cameras and projectors at

Chelsea. They had Super 8 projection at St. Martin’s.

Nina Danino:

As I recall, at St.

Martin’s in 1976, there were no Super 8 cameras in the film unit that Malcolm

Le Grice had set up with William Raban in the basement of the main building at

Charing Cross Road. They were working with 16mm.

Anna Thew:

By 1982 (in Long Acre),

that had changed. Derek Jarman was using Super 8 at the Slade and Anne was

using Super 8 as diary film in 1972

(at Chelsea). So the use of Super 8 was nothing in particular. It was cheaper

than using 16mm. You could have sex scenes in Super 8. You could do all sorts

of naughty things because no-one in the lab sees it. It's automatically

processed, so there were certain things that you could do with Super 8 that you

certainly couldn’t do with 16mm. So you see some scenes with boys cuddling in

John Maybury’s films and post punk chest slashing films so on and so forth.

Those wouldn’t have been so easy to get through laboratories if they had been

on 16mm. Super 8 had this kind of privacy for the person making it. I used

Super 8 and 16mm. Anne Rees-M made a triple screen Super 8 film, Red Green Blue, which was shown in the

1981 Summer Show. She also documented a nephew of hers, Little James, on Super 8.

Nina Danino:

Super 8 became a group

identity for some artists.

Anna Thew:

That is just something

which is written about in a certain way, but the actual reality of it, is that a group called Alle Macht der Super Acht [All Power to Super Eight] came over to the Co-op in 1981, invited

by Jo Comino and they showed their films. They stayed at the Goethe-Institute

and there was a great debate. The programme,

Alle Macht der Super Acht, was touring. It went to the United States,

courtesy of the Goethe Institute and Padeluun stayed in my house. He and I had

a little, sort of, thing. Then he met Derek Jarman and he appears in Derek’s SUPER 8 book, looking into a crystal

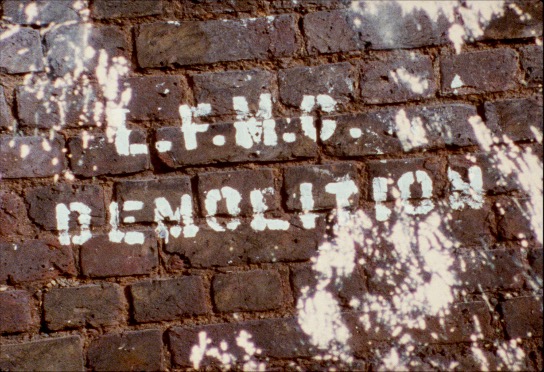

ball. There’s a link there with British Super 8 and Padeluun then invited me to

go to Berlin and to programme Filme der

Mitarbeiter an der London Film-makers’ Co-op (Films of the Workers at the LFMC)

in the Counter Film Festival (1982) and Padeluun is then in my Berlin Meine Augen (Berlin, My Eyes), double

screen (1982). So, that whole Super 8 thing at the Co-op started with Padeluun

and with me and Jo Comino, Thomas Mutke and Bruno de Florence, when we came

back from Padeluun’s Counter Film Festival

in Berlin. We were full of it. Double, triple screen. That’s when Super 8

began as a movement…at the Co-op!

Nina Danino:

Could you say more

about what you think is the post-interpretation? Everything is to some extent

post-interpretation including our talk right now.

Anna Thew:

There are certain

things that have been written in books. When something gets written by somebody

who’s not even necessarily been

there, they contextualise it in the terms of what they’ve read, or heard

elsewhere. So the history of this period depends entirely on who scrivened what

at the time, not on what actually did

happen.

Nina Danino:

What, in particular, do

you think has been misinterpreted about the Super 8 camp?

Stills, Darren Birch (left) and Etruscan arch in Perugia (right)

from Anna Thew, Fragments for Eye Drift double screen, Super 8

blown up to 16mm, 2005).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Anna Thew:

Well, the start of

Super 8 as a movement in Britain, in London, was to do with Padeluun. It was

completely and directly to do with

Padeluun. Padeluun came over. He’s an incredible character. He’s still very,

very active and he’s doing things about Big Brother (in the Orwellian sense)

and about surveillance. We’re still in touch. As said, he invited me to do a

programme of films at his Counter Film

Festival at Café Mitropa in Goltzstraße, Berlin. At that point I was lent a

Bolex Super 8 camera and some money for stock by George Stamkovski who’d been

James Mackay’s boyfriend but was now bi, and I made Berlin Meine Augen (Berlin My Eyes), as a double screen film. At

that point my double screen and triple screen came, not from any knowledge of

expanded cinema at all. I was working on drawings and on paintings in series at

home, so I took the triptych and diptych in painting to film. The 100ft 16mm

loops in Blurt, were projected onto

two painting stretchers suspended from the ceiling in the London Musicians’

Collective in the 1983 Co-op Summer Show. So expanded, multi-screen work is

directly related to painting and collage works in series.

Nina Danino:

Can you talk more about

Alle Macht der Super Acht from

Berlin?

Anna Thew:

The Super 8 influence

as a movement, came from Alle Macht der

Super Acht, which literally means “All

Power to Super 8”. They had a manifesto. This camera is light. You can hand

hold it. You can run around with it. It’s got time-lapse. It’s got zoom and

it’s got macro and you are free with Super 8! And it only costs you a fiver.

That was as much as a couple of drinks in the pub. You can get that film

processed the next day. If you were using Kodak 40 the processing was included

so you would get your film back the following day (from Holborn). They did this

manifesto and there was a huge Super 8 movement in Germany and France and

Greece (Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki, yes?) and Japan and Hong Kong

and Australia. The Super 8 thing in London was big when we came back from

Berlin in 1982. I showed Berlin Meine

Augen in Café des Alliés, Centre

Charles Peguy, Leicester Square, and as Split

City Rushes (1982) in Women Live,

I did a performance with it. That was the first time that Super 8 films that we

brought back from Berlin were shown. Jo Comino at the same time was making the

double screen, Spleen.

Nina Danino:

Super 8 was felt to

have a home movie relationship at the Co-op which was founded on 16mm

film-making. James Mackay says that Super 8 wasn’t taken as a serious medium.

Anna Thew:

Well, that was just the

stuffies. That was the problem with that.

Nina Danino:

Some work was in Super

8, and some was not – what was important was whether the work was good, or not.

Anna Thew:

Yes, absolutely. But we

acquired a Super 8 Steenbeck at the Co-op, because of that.

Nina Danino:

Super 8 was shown in

LFMC cinema programmes. It was pretty impossible to edit Super 8 other than

very basically. Super 8 had single frame and vari-speed, which when projected

at 3fps, slowed down the image and created a dreamy effect also often re-filmed

off the wall. Kodak film stock also had beautiful, saturated colours and grain.

I shot Stabat Mater (1990) on Agfa

Super 8. The format leads the aesthetics. It was also a light camera to handle,

and artists used it like a diary film and recorded their own social scenes. It

had single frame, time lapse, vari-speed and most importantly - a macro lens,

and automatic light meter, which could be switched to manual.

Anna Thew:

Yes, and we also had

three GS-1200 Xenon Super 8 state of the art sound projectors with a 50 foot

cinema throw. Cordelia (Swann) unfortunately ought to have a mention somewhere

here, as she started Experimenta at

the London Film Festival with single and multi-screen Super 8 in 1985 and I

showed Sailor Trailer and the Tinkling Laughter of Little Girls (triple

screen, 1984) and then she started Pandaemonium

at the ICA, 1996 and then at Lux, 1998, with Michael Mazière.

Nina Danino:

These conversations are

about subjective inscription through film language as we’ve been saying.

Anna Thew:

The Super 8 thing was

diverse. There was a whole movement, S8

at B2 at B2 Gallery, Met [Metropolitan] Wharf; Women Live (1982) at the LMC [London Musicians’ Collective] and

LFMC; Leicester Super 8 Film Festival (1984 onwards). The Arts Council/Film

Video Umbrella New British Super 8 Film

(1984), with single and multi-screen touring programmes curated by Mike O’ Pray

and Jo Comino; The New Pluralism

(1985) curated by Mike O’Pray and Tina Keane at the Tate, then House Watch and on and on. It’s never

all been documented.

Nina Danino:

Would you say that

Super 8 is a big part of your film-making identity then?

Anna Thew:

Absolutely. Super 8 was

actually being focused by the film-makers who were working at the Co-op. There

was Steve Farrer (Cinema 1980-81), Bruno de Florence (now B de F), Thomas Mutke

aka von Schulemberg (Co-op Directors 1981-85), Roberta Graham and James MacKay

(Cinema 1979-80), Christopher Hughes, Cordelia Swann, Jim Divers and Jo Comino.

There was Marek Budzynski, John Maybury, Cerith Wyn Evans and Plume Tarrant.

Bruno de Florence launched a big Super 8 event in 1982 with performance artist

Charlie P (then Charlie Pig) skinning a rabbit and with a rock band. We programmed a Long Night of Super 8 and an All

Day Super 8 on the Saturday in

the 1982 Summer Show. And with all those other people who I was working with at

the time, when Cordelia (Swann) did the shows at the Salon of 83 and 84 at the

ICA, there was no 16mm. It was

entirely Super 8, slide tape or video. There was a group of people, George

Saxon, myself, who were in each other’s’ films. George played Tom banging his

head against the wall in Hilda was a

Goodlooker (16mm). Gina

Czarnecki, D John Briscoe and I played in Pig

of Hearts (S8 to 16mm, 1993).

Nina Danino:

There were different

experiences of the Co-op in the 1980s and that’s fine.

Anna Thew:

I mean, yes, and that’s

absolutely fine. But what is not really

correct in my view, is this idea that Super 8 was just about John Maybury and

the New Wave invention. That is complete and utter tosh because some of the

biggest influence was Super 8, internationally.

We did have Derek Jarman’s Super 8 films blown up to 16mm from Dark Pictures in Co-op Distribution at

the time (thanks to Berlin ZDF). We had In

the Shadow of the Sun (1981), Home

Movies I and II (1972-77) and TG Psychic Rally in Heaven. The home

movie genre also linked to Anne Rees-Mogg who was terribly, terribly strong.

She was very active at the Co-op. She was Co-op director and chair through the

whole of that period until her death in 1984. We had a Super 8 section in

Distribution with Super 8 films by Stan Brakhage and Helen Chadwick, so there’s

a lot of filling in to be done.

Nina Danino:

The Co-op to me were

the conversations you could have with other film-makers, it was exciting and

engaged as well as critical and this was also after screenings. But some of the

so-called ‘New Romantics’ didn’t

discuss the work, so to me this seemed to miss the purpose of the Co-op.

Anna Thew:

But it wasn’t only

Super 8, you used whatever medium. When you got a grant for 16mm, you used

16mm. I mean, for me, I would swap from one to the other from 1980–2001, but

regarding Super 8, when I showed at

Interfilm in Kino Eiszeit, Berlin; Hamburg Lo-Budget Film Festival and

Super 8 Festival in Holland and France, there were Italian Super 8 film-makers,

Hungarian Super 8 film-makers, Hong Kong Super 8 film-makers. Jo Comino’s

documentary film for Channel 4 was about the use of Super 8 internationally,

and in North Africa and Venezuela, it was for political reasons. There were

also touring programmes of the New

British Super 8 Film (1984). Jo and Michael O’Pray took those all around

the world literally. They went to South America, Venezuela, Brazil, North

America, Hong Kong, Japan, Hungary and so on and so forth.

Nina Danino:

Of course, many artists

used it as a medium. They also transferred enlarged/blew up Super 8 to 16mm on

the optical printer like I did in Stabat

Mater and re-filming. Barbara Meter also talks about this. But we’re

talking about the experience of Super 8 as a movement, as an identity scene for

some artists in the 1980s. You are right is it also post-interpreted

particularly by Mike (Michael) O’Pray, who championed it through his writing

and curating.

Anna Thew:

You used Super 8,

because it was cheap. You used Super 8 as a diary medium rather than 16mm.

Nina Danino:

Is there an aspect of

your film language that you want to pick up on as a final question?

Anna Thew:

Well, my way of editing

and collage and my notions about editing? You said here, “your films are highly

crafted and laboured”. I wouldn’t use the word ‘laboured’ because that goes

against something that I would be trying to do. I work and work and work at

something until it turns out OK, using collage and chance procedures. Some

things you work on for a long time, like Eros

Erosion (1988–1990). Some things, like Terra

Vermin, double screen 16mm (1998), I filmed in an afternoon, assembled and

screened for Flux Projections at Free Radicals, a dance, music and film

season at Riverside Studios, the same week.

Nina Danino:

I was thinking about

16mm and that it’s not easy to make this work, not just the skill it needs but

of having to work at it and of film as a struggle. I don’t mean laboured in a

pejorative sense. On the contrary, I mean it as an intense type of engagement

with film as a language.

Anna Thew:

Ok. No, well, it’s just

that probably it’s not the right choice of word, because if something’s

‘laboured’, it means that it might

have had the spirit worked out of it.

Nina Danino:

I can see how it can be

interpreted like that, although sometimes experimental work can be laboured in

that sense too. It’s in the nature of it that one is discovering these limits.

Anna Thew:

Anyhow, one of the

things I think that is key to my work, is how I’m thinking about editing. I

will go to Hilda and to the idea

about the absurd, the subconscious, the oneiric properties of film, chance

procedures and Dada and the idea of automatic writing, drawing and filming,

which applies to my whole process.

Nina Danino:

The narrative in experimental films such as Eros Erosion composed of short shots and fragments, fleeting images

and come together in a collage in the editing. Perhaps you can say how chance procedures relate to how you edit

or how you film?

Anna Thew:

There’s a piece that I

wrote about my practice. I would very rarely write a script. I would normally

start from drawings, sketches, notes. Collage is there. It’s key. It’s the way

in which I was making drawings, making paintings. Doing collage, collage with

paper, collage with words. This is a practice that started a long time ago,

influenced by graffiti, slogans, peeling walls and torn posters in Rome. You’re

using those things that you’ve learned about and that you believe in. I

believed in the idea of eliciting from the subconscious. Rather like if you

think about Henri Michaux, or about Joan Mirò, or someone who’s making marks

like Jackson Pollock and out of those marks come an image and an idea…that

you’re intuitively accessing your subconscious. In Hilda, as with Eros Erosion, I

would have a plan of what I would film, but I would always film something else

when I was filming. Because I’m filming it myself. I’m seeing through the lens

myself and I’m not giving the camera to somebody else with a list. I can do

whatever I like. I got into the habit of doing a series of drawings and then

those drawings would be shuffled around and then I would decide the order in

which we would film certain scenes. Then you would always film/record/do

something which you hadn’t anticipated doing, like the sailor looking longingly

through the frosted glass at George [Saxon] and John [D Briscoe]’s house. It

was only because when Juan Lastera turned to the glass, he looked so wonderful

that I had to film him touching the glass. There are things that are

constructed, but at the same time there were things that were captured through

the lens, because you were using the camera yourself.

Nina Danino:

That’s something we

have discussed in the other conversations, the difference between handing over

the camera and looking through the camera and how that’s also the difference

between experimental film practices and artists’ moving image.

Anna Thew:

It also secures a

different response from the subject. The guy in Eros Erosion (Toni Dominici) was a boxer. He couldn’t read or write. He was terrifying

in action. I just showed him what I wanted him to do… pounce on Lisabetta’s

lover Lorenzo and kill him – and he (Toni) was much better at it, than if I’d

have tried to demonstrate. He looked fiercely straight into the camera. You’re

behind the camera. You’re talking to him, so he looks at you through the lens.

I never forget when Eros Erosion was

first premiered by the BFI in the Metro Cinema, off Leicester Square. People

were being a bit funny because it had had a bad review from Geoff Andrews in Time Out. When my film came on there

were people in the audience muttering, “Oh, this is the arty auteur film with the portraits that he

says you shouldn’t like.” Then, when the stunning boxer, Toni Dominici comes up

and he turns towards the camera and blows smoke through his nose, the whole

place went quiet. What a find! I don’t think you can imagine or get an image

like that if you ask a cameraman to

do that. You’ve only got that because there’s a relationship with the

film-maker, camera person/woman and the subject.

Nina Danino:

Do you think that this

moment where there is a connection with the viewer can only happen when the

film-maker is behind the camera?

Anna Thew:

Yes. There’s something

about observing through the camera

lens… when you look at people and people look at you at me as the woman,

the personality that I am. You actually capture their glance through the

camera. You see it in Anne’s films, in George’s films, in Derek’s films, in

Warhol, in Brakhage, in Schneeman, in Robert Cappa, in Victoria Mayer, in

Pasolini. Pasolini used this phenomenon in Oedipus

Rex (1967). He has a second camera and hand holds it… with Jocasta and

Edipo, cross cut, eye to eye, in POV (Point of View), “I killed my Father!”, straight into the camera, straight at you. Not, “I slept with my Mother…”, but the critical irreversible destiny

bit, “I killed my FATHER!”.

Nina Danino:

Pasolini worked with a

cameraman and big crews. To see him sitting pensively in a big production like

a director. He was not an experimental filmmaker as such.

Anna Thew:

He used POV in Oedipus Rex. It’s not just a fake point

of view. You’re not having somebody looking out over here. It’s not somebody

like Michael Caine looking with one eye at the camera and one eye at the

director, as Caine explained in a documentary, but you’re just looking through

the lens. That’s also why you have difficulty with a video camera. The video

camera has a little flap at the side, so they’re not looking through the lens

anymore, they’re looking slightly to the side. This, direct personal relationship,

is like somebody you know. I will never forget seeing Derek Jarman’s B2 Movie at the Co-op Summer Show 1982.

Jean-Marc Prouveur, whom I later got to know very well, is slowed down. He

looks into the camera at you and you

see his eyelashes moving up and then he looks away. You felt that this was

somebody you knew, because he’s looking straight into the camera at Derek, now

at you, at me… I think that’s

something that’s very powerful. Think of Window

Water Baby Moving (1962) where Jane takes the Bolex and films Brakhage seeing the birth, the instance…

Nina Danino:

The actor looking at

the camera and appearing to connect with the viewer could be a rhetoric of

connection, like with slow-motion where the movement is magnified. These

effects can be overused not just in Super 8, but special FX in post-production

that became available to artists, could they be clichés – at-hand languages?

Anna Thew:

I don’t think they’re cliché. This is not a cliché.

Nina Danino:

How do you distinguish

between when it is a cliché or a moment where the look is active and conveys

something that doesn’t have words? How do you know what distinguishes the use

of slow motion or other special FX from a cliché?

Anna Thew:

I think there are very,

very big similarities in the way that the work was happening in the little

group that we belonged to.

Nina Danino:

The practice of ‘coming

out’ was a big part of the 1980s. You say that “in the ‘coming-out’ films of

Steve [Farrer] and Jeanette Iljon, there had to be

the gay subject and camp, obviously so, with dressing up, using dancers or

performers”.

Anna Thew:

I think there’s a

confusion about the idea, about camp and gay, because to me it was just

something where we’re theatrical. I think there’s something that is very much

misunderstood about the dynamic at that time.

Nina Danino:

What do you feel has

been misunderstood? There was a feminist critique of how women are marginalised

by parts of gay subcultures which parodied women. But the way that this scene

worked at the LFMC is that perhaps that it offered an exit from the austerity

of structural film, flamboyance was perhaps a sort of way out, a reaction.

Anna Thew:

You have to understand,

that say when in Split City Rushes,

which became Berlin Meine Augen (1982),

I sang in front of the film, but when we did it at the Summer Show, we cut a

hole in the (Co-op) ceiling and I was lowered in front of the film on a rope,

with little blue boots and red leopard-skin tights. I’m not gay but the people

who liked that performance most of all, were people like Bruno de Florence and

Thomas (Mutke) and big Steve. They adored those types of things. They might

have liked what they considered to be camp in what you do. Just being “near to the theatre” was something that

I and my Mother always liked.

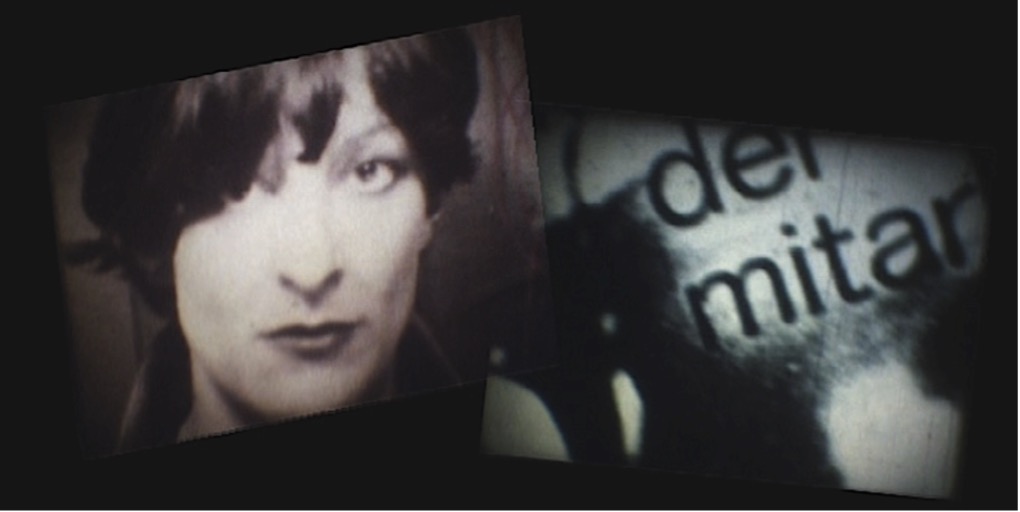

Still

of Anna Thew and Filme

der Mitarbeiter catalogue from Anna Thew, Berlin Meine Augen (double screen, Super 8, 1982).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

Camp is over theatrical

and is it problematic if it veers into pantomime? I see excess as something

different. The ‘feminine’ which is in ‘excess’ is something that cannot in fact

be represented. It exceeds representation in symbolic language, so it is a

different direction. The Super 8 scene connected to extravagance that’s far

away from the inscription and the subjective that we are talking about. Perhaps

we can look more for inscription in your solo self in the 16mm films.

Anna Thew:

I’m not sure… Well, I

did love Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks (1947). There’s no doubt about the sailor in Hilda, Juan Lastera being gay, or

undecided. I’m making a direct reference to Kenneth Anger, because I swap their

hats. One of them has an American sailor’s hat in one scene, which is then

swapped for a British Navy hat.

Nina Danino:

In Fassbinder’s Querelle?

Anna Thew:

Oh, Querelle? I hate Querelle for its suffocating hyper-bourgeois mise en scène and actually Jean Genet refused ever to have any of

his novels used for film, after that film.

Nina Danino:

Un Chant d’Amour (1950) in

distribution at the Co-op. It was so often programmed and shown there that you

said that he made quite a bit of money from the film, and you paid him

royalties directly to his Paris address. That’s quite amusing to think of that

today when it has become such an icon of avant-garde cinema.

Anna Thew:

I only knew who Jean

Genet was because my Mother introduced me to The Journal of a Thief (1949), which she considered to be a

masterpiece, but backed it in brown paper so Daddy wouldn't know what she was

reading, like the Kama Sutra and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928). I think

she was explaining to me, “I know it’s really naughty to actually really like

this, but you see…” and she said, “I suppose women look at men, like gay men

do,” and this is what she was saying.

Nina Danino:

You say, “We were beyond feminism” and describe yourself as “an androgen tomboy”. Can you say more about this?

Anna Thew:

Not like gay men, but that women look at

men… they’re desirous of men, like gay men are, no more. We had Un Chant d’Amour in Distribution and the

dynamic at the Co-op at that time was gay and ‘polymorphous’. Steve was gay and

Jeanette Iljon was a lesbian. Mick Kidd (BIFF) was into the Co-op and loving

everybody. George was gay or bi. It was Steve who started up the Women Only screenings, not Jeanette. He

made it possible. Many of the women who were part of Co-Option, Channel 4 mega

funded women’s only project, became very badly behaved and tried to take over

the Co-op and cut men out. Thomas and Bruno organised the first Gay and Lesbian

Festival at the Co-op in 1981. We were all involved, as they

were with the first Distribution Preview Shows and the Summer Shows (1981/2).

This was very typical of the time, like in Isaac Julien’s film Young Soul Rebels (1991) and he’s

telling a story of his childhood. There were three/four friends at school, a

straight guy, a gay guy and two girls, and they were all really great friends.

It was only when they get into the outside world, that separations begin to be

unnaturally forced on them.

Nina Danino:

Do you

think your films are also a record of this scene, people, artists from the gay

subculture of the eighties including Derek Jarman and others?

Still

from Anna Thew, Cling Film (1993).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Anna Thew:

We had the Thompson

Twins playing. We had parties. We went clubbing. We were very naughty. There

was the first gay and lesbian festival in 1981 and September in the Pink in 1983. When Thomas (Mutke) was running The

Fridge night club and Daisy Chain in

Brixton, he used to give us money to do 16mm loops. Thomas and Bruno did Network 21, Pirate TV. They did the

first Scratch Video shows at the ICA, the first multi monitor Video Lounge and the first video wall at

the Fridge night club. Some of my films, like Cling Film (1993) were shown on the Fridge video wall for weeks.

Nina Danino:

Yes, the

Super 8 scene was connected to venues outside the LFMC. There were nights and

events. There was a group around Derek Jarman and B2 at Metropolitan Wharf.

Were you involved in that grouping around Jarman? He had a cameo in your film Behind Closed Doors (1988), did you have

cameos in other films? Perhaps this is a form of inscription in a collaborative

group.

Anna Thew:

Well, I would say that

a film like Berlin Meine Augen, first

shown as a (double screen) film at S8

at B2 and my performance of Split City Rushes (1982), set off a thing or two about

multi-screen 16mm, Super 8, and performance with film. There are a few things

that I’ve done, that have sparked other people to do. I think some of George’s

early performative films like Wall

Support (1977), which he made when he was at the Royal College, where he

just bangs his head against the wall for 10 minutes, had the same effect on me,

so George was the obvious candidate to play Tom, who bangs his head against the

wall in Hilda. Steve, George and I

were the Three Musketeers.

Nina Danino:

Would you like to talk

as a solo film-maker about your narrative in experimental films using 16mm? Eros Erosion and Hilda was a Goodlooker?

Still

of Juan Lastera as Billy the sailor in Anna Thew, Hilda was a Goodlooker (1986).

Anna Thew:

It was all supposed to

be very mixed up and deconstructed. George was in my film and he’s dressing up.

Then I’m in his film and I dress up, but was George influenced by me making

those films, or me by him? I’m coming slightly from German (Brechtian) theatre.

I’m into Garcia Lorca. We dress up. That’s the difference, the dressing up.

There is something which connects our theatrical

films to the films of somebody like Jack Smith, or Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren,

or Manuel de Landa’s The Libidinal

Economy of Filmus Interruptus (1980),

or the kind of scene in American cinema that you get very little of in the

British, rather reformative avant-garde. So there was this helping of each

other. I think that more than our filmmaking, or at least my film-making, when

it’s got more than one person in it, it’s a collective effort. You have

somebody suggesting that you do something in a certain way when you’re filming.

So somebody might suggest, “If you do it like this… ” There was a really,

really active group of people, who actually supported each other’s work, and I

would say someone like Nick Gordon-Smith, like Carole Enahoro. The people who

were working at the Co-op and making films, like Alia Syed’s early work, trying

to use words, trying to use sound, trying to use text.

Nina Danino:

Your multi-media

expanded work like Blurt (1983) and On Leonardo (1977) hovered between

experimental theatre, super 8, performance and live events, which differed from

structural expanded film. There was the structuralist work still going on at

the LFMC in the 1980s.

Anna Thew:

Yes, but at

that time, it (structuralist work) was really quite secondary, frankly. BLURT was about words, that as Leonardo da

Vinci said, language cannot be

universal. Marcel Duchamp said, “Language is no damned good. It has to be

translated from one to another.” For the Blurt

video, I was reading all male texts in six different languages, (two that I

don’t know), untranslated and changing my hair style and clothes and delivery

for each language and text. It was a comment on talking head videos and

reparative voice over, on film. This video was on two monitors kicked on their

sides on the floor. There was a colour film with superimpositions of blabbing

lip-sticked mouths. Yes, straight men with lip-sticked mouths too, on one

screen and language in all forms, handwritten, wood block printed, Gothic

script in rhythmic patterns using varied factors of 24, so you would never tire

of watching it though you couldn’t understand a word. Word as image in black

and white. But if you don’t understand, you fall out. I trained to weave (a boxing term) at the Tabernacle

with a black heavy weight boxer and kids in stitches all around, with me in red

silk Lonsdale boxing shorts and I terrified my drag queen friend Charlie P with

my convincing movements… and in Osnabrück (Experimental

Film Workshop, 1987), it was re-staged with Padeluun and then with Caspar

Stracke and me and Lukas Schmied doing the fox trot. So deadly earnest, but

absurd.

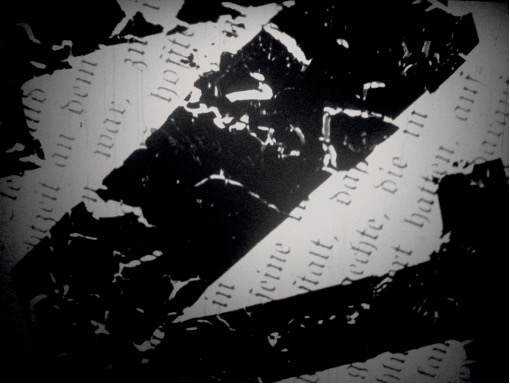

Stills

from Anna thew, BLURT (double screen,

16mm, with live performance, 1983).

Copyright

Anna Thew. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Danino:

It (structuralism) did

remain in place at the Co-op.

Anna Thew:

It’s definitely very

much to do with the kind of religion that we had in Britain. It goes right back

to how Voltaire thought it was terribly funny when they had the Quakers and

everybody was wearing grey and they all trembled. This idea about people wearing

grey and the lack of the use of colour.

Nina Danino:

There were also strands

which came from the formal rigour of structural film, but which then combined